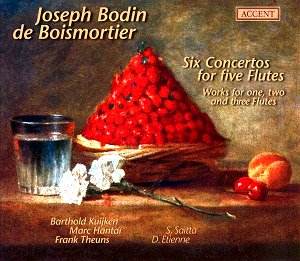

Joseph Bodin de Boismortier

was perhaps the very first free-lance

composer in history. Being born in Thionville

in Lorraine as the son of a confectioner,

he went to Perpignan in 1713 and established

himself there as a collector for the

Royal Tobacco Excise Office, a position

he held the next ten years. He must

have received some musical training,

though, since in 1721 a drinking song

by a 'M. Boismortier de Metz' was published.

His musical activities increased and

he went to Paris, where he received

his first permission to publish music

in 1724. He published duos for transverse

flute and cantatas, which was the start

of a career as France's most prolific

composer in the 18th century, whose

oeuvre consists of more than 100 opus

numbers with instrumental music, and

in addition to that cantatas, motets

and some stage works. He also was active

as a theorist, writing treatises on

the transverse flute and the 'pardessus

de viole'.

But Boismortier was

also the victim of sharp criticism.

According to some the size of his musical

output went at the cost of its quality.

He was specifically accused of writing

easy stuff, which could be played by

amateurs with limited technical skills.

The theorist Jean-Benjamin de La Borde

wrote that "Boismortier appeared at

a time when people only liked music

that was simple and very graceful. This

clever musician profited all too much

from this fashionable taste ...". Boismortier

wasn't making any excuses, as de La

Borde writes: "Boismortier, in reply

to these criticisms, said: I make money."

One has to assume, though, that he also

had didactic motifs, as the writing

of the above-mentioned treatises suggests.

And this can be directly linked to the

spirit of the Enlightenment, gaining

ground at Boismortier's time.

Boismortier may have

written a whole lot of music in response

to the growing demand of music which

was not too difficult to play, he was

breaking new grounds in several ways,

and some of his music is very original

in concept. The Concertos for 5 transverse

flutes opus 15, which are recorded here,

are a good example. Never before had

any composer written any music for 5

instruments of the same range without

a bass. And in addition to that, Boismortier

was one of the first French composers

to use the Italian form of 'concerto'.

And indeed there isn't much French in

these concertos. All movements have

Italian titles: allegro, adagio, largo

and affettuoso. Boismortier also abandoned

any prescription of the ornamentation

which was so characteristic for French

music. The title of 'concerto' suggests

a contrast between 'soli' and 'tutti',

and that is indeed the distinctive feature

of these concertos. The five transverse

flutes are not treated as equals: in

most concertos one or two play the leading

role, whereas the others play the 'tutti'.

And although the concertos don't have

a part for basso continuo, one of the

flutes is in fact acting like a bass.

One could compare these concertos with

the 'concerti da camera' by Vivaldi.

It isn't in the concertos

for five flutes only that the parts

are treated differently. Even in the

Sonata for two flutes from opus 38 the

two flutes are no equals: the first

flute is dominating, although both instruments

are in dialogue in some passages.

The sonata for flute

solo which opens this disc is one of

the most typically French pieces of

the programme: it starts with a 'prélude',

like so many suites by French composers,

and this is followed by four dance movements.

This sonata can be played with or without

basso continuo. Also French in style

is the Sonata for three transverse flutes

from opus 7, in four movements with

French titles. Sometimes the three flutes

imitate each other, in other instances

they follow their own route.

This disc shows Boismortier

at his best. All pieces on the programme

are delightful and entertaining, and

they get the best possible performance

here. The ensemble playing is immaculate,

and the sound is delicate and refined.

The tempi are well chosen, and phrasing

and articulation are clear. Of course,

the dynamic differentiation is very

important in these concertos, and this

is dealt with very convincingly. I especially

enjoyed the Concerto no. 3, which is

one of the most Vivaldian, and whose

fast movements are played with great

panache. And Barthold Kuijken gives

a very sensitive performance of the

solo sonata.

The above-mentioned

theorist Jean-Benjamin de La Borde,

in spite of his criticism, acknowledged

that one may find some grains of gold

in the mine of Boismortier's oeuvre.

This disc presents nine of them in sparkling

performances.

Johan van Veen