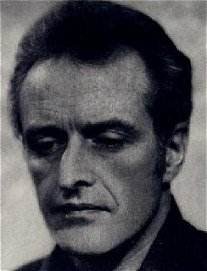

CARLOS

KLEIBER (1930-2004)

The

death of Carlos Kleiber at the age of

74 (and characteristically, his death

on 13th July took almost

a week to become public) ends perhaps

the most infuriating career of any of

the great conductors of the last century.

His last public concert – with the Bavarian

Radio Symphony Orchestra in 1999 – came

some years after his last studio recording;

and of all the great conductors he had

by far the most limited repertoire.

Like Sergiu Celibidache – whom Kleiber

recalls in many ways – his was a career

which was unsatisfactorily incomplete.

The

death of Carlos Kleiber at the age of

74 (and characteristically, his death

on 13th July took almost

a week to become public) ends perhaps

the most infuriating career of any of

the great conductors of the last century.

His last public concert – with the Bavarian

Radio Symphony Orchestra in 1999 – came

some years after his last studio recording;

and of all the great conductors he had

by far the most limited repertoire.

Like Sergiu Celibidache – whom Kleiber

recalls in many ways – his was a career

which was unsatisfactorily incomplete.

Yet,

however incomplete it may be there exists

a considerable artistic legacy, although

a certain blindness to Kleiber’s greatness

can have the effect of clouding some

of his real achievements. So much, for

example, has been written about his

recording of Beethoven’s Fifth with

the Vienna Philharmonic that it is often

overlooked that Kleiber doesn’t actually

get the first bar’s four note motif

right. Nor is he a persuasive conductor

of the Prelude to Tristan where

Wagner’s tempi are all but sublimated.

Yet, forget these technical details

and the performances that Kleiber gives

us were as musically perfect as any.

His conducting technique was so expressive,

so flexible, that at times he seemed

as if he was improvising. Like Furtwängler

no two performances were ever the same

and like both his father, Erich, and

Fritz Busch, the clarity given to the

grand line of a work was seamless. There

were few mannerisms – though Kleiber

did have a tendency to over-emphasise

crescendos to the point of starting

them earlier than written – and at times

one was less aware of dynamics in a

performance of a well known work than

with other conductors. Yet, at his best

Kleiber was an incandescent re-creator

of great music and a conductor of such

virtuoso brilliance that it seemed impossible

to be excluded from his music-making.

Such

greatness – effortless as it was – belied

the preparation that Kleiber put into

his performances. Rehearsals were intensive

and - like Celibidache and Wand – he

demanded, and got, the rehearsal time

he wanted. It was this search for perfection

that made Kleiber so hysterically unreceptive

to bad reviews. One of the most notorious

of these ‘bad press’ incidents happened

in London in 1981 when the LSO persuaded

Kleiber to conduct a performance of

Beethoven’s Seventh and Schubert’s Ninth

(a repeat of a concert Kleiber and the

orchestra had given in Milan days before).

Edward Greenfield’s negative review

ensured Kleiber never conducted an orchestra

in London again. Kleiber forbid the

BBC to broadcast the concert and the

tapes were destroyed. Incidents such

as these were few and far between, but

it was characteristic of Kleiber to

be so vulnerable to negative publicity;

he never gave an interview, thus perpetuating

the myth of his reclusivity.

Kleiber

was born in Berlin on 3rd

July 1930 but moved to Argentina soon

after when his family left Nazi Germany.

Kleiber almost instinctively knew what

his vocation would be – to the extent

that his father expressed displeasure

at the young Carlos’ unfortunate interest

in music – and so it was that the young

Kleiber took the then conventional route

of working his way up through European

opera houses, first in Düsseldorf

and then in Zurich. Stuttgart played

an important part in Kleiber’s operatic

life in the mid 1960s, as did Munich

later – and his special relationship

with the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra

became a natural extension of operatic

Munich. The early 1970s saw his debuts

at the Vienna Staatsoper, Bayreuth,

La Scala and Covent Garden. It was only

in the late 1980s that Kleiber made

his debut at The Met, although he had

regularly conducted the Chicago Symphony

Orchestra throughout the previous decade.

Kleiber

never held any post with a symphony

orchestra, preferring instead to guest

conduct those orchestras who could most

meet his demands. The Berlin Philharmonic,

Vienna Philharmonic and Concertgebouw

all secured his services (the Berliners

even electing Kleiber to succeed Karajan,

only for him to turn down the job.)

Kleiber negotiated all his contracts

personally – often with a handshake

rather than in any written form – and

never had any agent to deal with managers

on his behalf. This sometimes led to

odd payment arrangements – one of his

last concerts involving payment in the

form of a sport’s car rather than cash.

But

it was the sheer sparseness of the concerts

that he gave that is astonishing for

such an important conductor. Between

1978 (in Chicago) and between that final

concert in Cagliari in 1999 Kleiber

gave just 157 concerts with eight different

symphony orchestras, an average of seven

a year. Some works – such as Beethoven’s

Sixth – he conducted just once (1983)

whilst other works he conducted merely

a handful of times - Ein Heldenleben

(twice) and Butterworth’s English Idylle

(five times.) Only Beethoven and Brahms

were conducted with any regularity.

In stark contrast, Kleiber conducted

over 520 opera performances over a 35-year

period, the majority of those having

been with the Bavarian State Opera.

At Covent Garden there were fabulous

performances of Elektra and Rosenkavalier

and at Bayreuth he conducted Tristan

for the three years between 1974 and

1976.

That

Elektra, released some years

back on Golden Melodram (a Slovenian

label, and Kleiber was buried in Slovenia)

still has the capacity to electrify,

even though the sound is poor (this

was an in-house recording). It’s an

important document of Kleiber at the

peak of his powers – has Strauss’ score

ever sounded more violent and more turbulent

than it does in this 1977 performance?

It’s also important because it demonstrates

those essential characteristics of a

Kleiber performance – crystalline textures,

subtle dynamics and absolute control

at all the pivotal moments. Yet, perversely,

the recording demonstrates a constant

throughout Kleiber’s operatic career

– his inability to cast productions

completely successfully. Gwyneth Jones’

Chrysothemis is poorly sung, and a similar

problem exists with his casting of her

as the Marschallin in both a 1977 Munich

production of Rosenkavalier and

another one in 1979. Marion Lippert

in a 1971 Elektra from Stuttgart

is also uncomfortable as Chysothemis,

yet that is slightly offset by a wonderfully

sung Klytemnestra from Martha Mödl

and a powerful Aegisth sung by Windgassen.

When it came to Tristan there

could also be controversial casting

choices: Catarina Ligendza – a regular

Isolde for Kleiber at Bayreuth, Vienna

and Stuttgart – never really settles

into the part but perhaps most controversially

was his insistence on Margaret Price

as his Isolde for his studio recording

of the opera done with the Dresden Staatskapelle.

The most sumptuously lyrical Isolde

on record, Price is either to your taste

or she is not.

One

could argue that Kleiber’s judgment

when it came to the suitability of releasing

some of his live recordings was also

defective at times. The recent Beethoven

Sixth on Orfeo is extraordinary

is some ways (notably for some really

beautifully judged orchestral playing)

but in others – its extremes of tempi

especially – it seems not to represent

Kleiber at his best. On the other hand,

Kleiber forbid Sony to release a 1983

performance of Ein Heldenleben

with the Vienna Philharmonic because

he was unhappy with it: listen to the

performance and one wonders what Kleiber

could object to. It is incandescent,

and as perfect an example of ‘clock-time’

being meaningless as in any recording

of the work I know. At less than 38

minutes it is fast - but it never sounds

it – and the architecture of the work

has never appeared so convincingly done

as it does in this performance.

And

that is the colossal scale of Kleiber’s

life and death. There exist some of

the greatest recorded performances of

symphonies and operas anywhere in the

catalogue (are there many people who

would deny that his Der Freischütz

is the greatest opera recording ever

made?) Kleiber does what every great

conductor does – he brings to a work

something personal and unique. There

is little – if any - Kleiber that remains

to be discovered but the legacy we have

is as important, and in many ways more

important, than some of the legacies

of great conductors who performed and

recorded with a considerably greater

degree of vicissitude than Kleiber did.

His death is a significant loss, but

given Kleiber’s rejection of music in

his last years not one that should be

mourned because of what he did not conduct.

Marc

Bridle