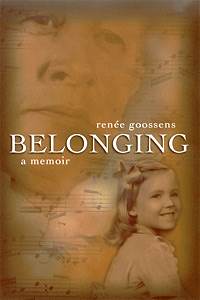

EXCERPTS FROM

BELONGING – a memoir

By Renée

Goossens

Published by

ABC books 2003-09-04

purchase

from abcshop.com.au

Copyright material

Memories of the

conductor and composer Eugene Goossens

by one of his daughters

Going to a concert

- Australia

The chauffeur collected us from Wahroonga

as he always did before a concert. It

felt very grand. I had never been to

a concert before. In New York, they

had always said I was too little to

stay up so late. (But now I was seven

years old.)

During the journey it was already becoming

dark, much earlier than it used to in

New York. Crossing Sydney Harbour Bridge

was particularly beautiful at night.

We counted the illuminated ferries and

an ocean liner festooned with strings

of lights which made it look like an

enormous, peculiarly shaped Christmas

tree. With the water sparkling, it was

much more beautiful than anything I

had ever seen before.

Parking at the Conservatorium, we went

straight to Daddy's rooms. The Director's

Studio it was called, one huge room

with a lustrous grand piano, a dark

brown leather sofa and several comfortable

velvet arm chairs. There were French

doors opening onto a terrace leading

to a tropical garden which overlooked

the Botanical Gardens and in the distance,

dancing water.

"Is this really your room, Daddy?"

I asked, running into his outstretched

arms and enjoying a hug.

"Yes, my little one. This is where

I work. Piano students come for auditions.

I rehearse with the Chamber Music groups,

rest before concerts, and talk to members

of the staff and the orchestra. The

sofa is comfy enough for an afternoon

nap. It's a quiet place for composing,

too. I rather like it."

"Time to go, Gene dear." My stepmother

was keeping an eye on her watch. Daddy

liked to be at the Town Hall at least

half an hour prior to a concert. Donie

had walked down ahead, to tune her harp.

Sydney Town Hall was dark, tall, wide

and seemed to me to be a very old building.

But once you walked up the stairs —

we usually went in by a side entrance

—and across the foyer, it was like being

in a film. Glass chandeliers hung from

the ceilings which were painted with

gold around the edges. It seemed enormous.

We went straight to the Green Room,

which was a large space with brown walls,

lots of dark wood, rather dreary and

no green anywhere at all.

"Why is it a Green Room, Daddy?" I

asked.

"It always is, little one. Don't ask

silly questions."

His reply made me wonder if he really

knew either. To the side of The Green

Room was a small room with 'Private'

on the door. Daddy put on his bow tie

and dress coat in there. Then he came

out, looking so very handsome, tall

and important that I was totally proud

of him.

A man in a black suit and bow tie collected

us, then showed us to our seats in the

Eastern Gallery. I loved settling down

early, listening to the chattering audience

and to the exciting sound of the tuning

of the orchestra. All those different

hesitant noises, some perfect, some

peculiar, some scratchy as tunes were

played, all at different times.

I could see my sister, sitting calmly,

her feet on the pedals of her harp finishing

her tuning, patting her arms against

the strings but I couldn't quite hear

the sounds she was making against the

volume of the other instruments.

A hush fell over the hall, voices cut

off abruptly as they do on the radio

before the voice of an announcer is

heard. There was a boisterous, friendly

clapping of hands as Daddy walked on

to the little stand in the centre of

the stage, climbed up, bowed to the

audience, then turned his back to us

as he paid attention to his orchestra.

The music began.

The first item was the Overture to

Wagner's The Mastersingers. It

overwhelmed me. Sometimes a piece of

music would flood into me and I would

have to hear it over and over again,

playing it all day, given the opportunity.

I never grew out of that habit. Nothing

else in the programme made any impression.

A pianist played beautifully, but the

vitality of the opening piece was so

important that I wished to hear no further

sounds. It came back into my head, playing

with a constancy which drowned all else.

I was mesmerised.

At interval, we went to see Daddy,

who was splashing himself with something

from a bottle labelled Bay Rum to freshen

himself up, I suppose, rubbing himself

down and looking red in the face but

very happy.

"Daddy, I adored that first piece.

Can I hear it again? Do we have a record

at home? Will you teach me all about

it, and the story? I read my programme

notes but they don't tell me enough."

"I'm glad you liked it, little one.

Yes, I will tell you more, later. But

now go back to your seats or we will

be late with the second half."

A misunderstanding

about recordings

I read in the ABC Weekly that

there was a concert at eight a.m. on

the very next day, with the Sydney Symphony

Orchestra and Daddy conducting. It seemed

peculiar that nobody had mentioned it,

for I had never heard of him having

to be at work so early. It also seemed

unfair that he had to work on a Sunday.

I knew he liked to be in the Green

Room half an hour before the concert

began. The car journey took about an

hour. So I decided I had better wake

him at just before six a.m. He always

had breakfast alone in his room.

I had watched Sven preparing breakfast

so I knew just what to do. It had to

be Indian Tea in a heated pot. One hard-boiled

egg, just three and a half minutes,

with two slices of toast and butter,

with Dialectic Marmalade as Daddy insisted

it was called, because Daddy was not

allowed sugar. Of course, I must not

forget the five prunes.

Pleased with myself but also a little

apprehensive, I knocked on the door

at five past six. The room was very

dark, as there were double curtains

on the windows, and the walls were a

sombre green. Heavy, wooden furniture

made the place even darker, so it was

difficult to find my way across to open

the curtains. Music was strewn all over

the lid of the black piano, and I nearly

tripped on the thick pads of scores

on the floor.

"It's me, Daddy. Good morning. Here

is your breakfast. I thought I'd better

get you ready for your concert this

morning."

He was flabbergasted, and not at all

pleased.

"What concert?" he asked, and I felt

very important at being the only person

who knew.

"I read about it in the ABC Weekly.

It's terribly unfair for you on a Sunday

morning, so I've given you extra marmalade.

I suppose the hire car will be here

in a moment."

"Listen, you silly child. Haven't you

ever heard of records?"

I was too wounded to reply, and walked

towards the door, feeling disgraced,

wondering why the orchestra and Daddy

would be on a record when people could

come and see them instead.

"I thought recordings were only of

dead people," I said mortified, as I

reached the door.

"You'll be dead too, if you do this

again," he said, then called me back

when he saw the tears streaming down

my face. He hugged me, kissing me on

both cheeks against his stubbly face.

"Now run along. We'll talk later about

the music you enjoyed last night. But

first of all what I need is some more

sleep."

Just before lunch, Daddy called for

me by ringing his large bell. It was

our special signal, and just hearing

it excited me. I knew the importance

of the bell, and it certainly was loud,

in our big house. I had been sitting

outside by the tennis court and was

still able to hear it, right from the

other side of the house, in his composing

room.

The bell was one of a set of six cow

bells he had brought back from Italy,

in his hand luggage. He adored their

sounds and wanted to use them in a composition.

He had not minded in the least that

they weighed eight pounds each, even

when the man at the airline desk made

him pay what he considered a fortune

in Excess Weight. I used to love hearing

about it. When he told everybody the

story, he loved to exaggerate wildly,

making it more amusing with each telling.

But as he only rang the bells when he

wanted to see me, I was afraid he might

still be angry about my silly mistake.

"There's a surprise for you on the

floor. I found it for you last night.

It's the piano reduction of Die Meistersinger

von Nuremberg. You seemed so excited

about the overture. If you are a good

girl, I'll play some of it for you after

lunch. I've got some work to do until

then. Run along again now."

We had lunch outside, on the veranda

by the tennis court. Our new Dutch cook

Nell had prepared roast lamb with all

the trimmings, such as Daddy liked best,

and a heavy Dutch style pudding the

closest she get to an English steamed

pudding. Everybody was in a good mood.

"May we, Daddy?" I asked, with nothing

but The Mastersingers on my mind.

The moment pudding was finished, he

took me by the hand to his precious

shiny black piano. It had been shipped

out from England and had belonged to

his father who had also been a well-known

conductor. The instrument had been damaged

in transit and the music stand did not

stay up properly. He propped it up with

two pairs of scissors, which made it

look rather odd, but served the purpose

and he did not want anybody 'fiddling

about to fix it'.

He began to play the first melody on

the piano. "This is how it goes, as

you will remember from last night. Wagner

introduces his themes, as if they were

people, so that when you listen to that

tune, you can expect the person, or

something about that person in the story

to appear."

Spellbound, I listened as he explained

the significance of leitmotifs,

(leading motives) together with the

plot, and the lives of the people taking

part in the contest after which the

winner of the song would be given the

hand of Eva, Pogner's daughter.

"What if Eva doesn't like the winner?"

I asked with utmost concern.

"That's the secret you'll discover

when you see the opera," Daddy replied,

entering into my spirit of excitement.

"May I, Daddy, may I? When? Where?

How?"

"Sit down, child, you're getting far

too excited," he said, flustered by

my enthusiasm.

"Rehearsals begin very soon at the

Con, and once the singers have tidied

themselves up a bit musically, you may

come and sit in. It's a treat, though.

You cannot come to every opera, or you'll

be up every night. I think this one

will be your special introduction."

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

* * * * *

Nothing else seemed to matter to me,

my cats, the tennis court, the visits

to the beach, playing with my friends.

I awaited the rehearsals of The Mastersingers

as if my very life depended upon

it. I even asked if I could have a better

piano teacher, as I wasn’t getting on

with the woman in the village. I would

need to improve if I wanted to play

some of the tunes to myself. I found

a record and wore out the tracks of

The Prize Song, driving Nell

to distraction by singing the theme

endlessly.

"Other children, they sing the pop

songs, the jolly sounds which I hear

on the radio," she would complain.

.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

* * *

MORE CONCERTS

AND OPERA

After a concert one night I sat with

Daddy in the back seat of the hire car,

enjoying the special treat of discussing

next week's programmes.

He was going to introduce Stravinsky's

The Rite of Spring, and a work

by Scriabin, Poème d'Extase.

He hummed a few tunes from the second

piece, then stopped suddenly to say,

"Look at those lights, driver, behind

us. I could swear we must have someone

following us. Take another route and

see what happens," Daddy instructed.

His voice sounded amused rather than

afraid.

The driver turned down a side street,

tracked back through a few parallel

roads, and we emerged in Wahroonga more

quickly than usual. No car had followed.

"I'm very tired, so I'll go straight

to bed. See you in the morning," he

told me.

Ten minutes later two cars pulled up

outside. One was my stepmother and sister

Donie, the other a new hire car with

important guests. Meanwhile Daddy had

changed into his checked dressing gown,

couldn't find his slippers and was walking

barefoot through the living room, calling

out, "I can't find any Milo. Where

is the kitchen?"

Embarrassed to see people he did not

know, then some whom he did, he retreated,

hiding in my bedroom where I was feeding

the cats.

"Don't you really know where our kitchen

is, Daddy?" I asked, amazed "we've lived

here for almost a year now."

"Kitchens are of no interest to me,"

he said defensively." Although

I do enjoy making my own hot Milo in

my kitchenette. But the tin was empty."

Quickly I went to Daddy to save him

the embarrassment of being seen in his

shabby bedclothes. I told him that we

had important guests, from the theatre.

Stepmother had invited them, telling

their hire car driver to follow ours

but apparently they got a bit lost when

we changed directions. I thought it

was funny but was sad to see Daddy perplexed.

Daddy was not at all amused. He insisted

on a cup of Milo, and braved out the

evening, in his dressing gown, for the

visitors were old friends and he quickly

forgot what he was wearing.

Two of England's greatest actors were

among the guests. Dame Sybil Thorndyke

was beautiful, although to me she seemed

very old. She was specially kind to

me, even asking me about myself.

"What do you enjoy doing? Are you going

to be a musician?"

"Daddy has promised to take me to the

rehearsals for The Mastersingers.

I absolutely adore opera but I haven't

been to one yet," I replied enthusiastically.

"You must come to one of our plays.

Come and meet my husband."

Her equally famous husband, Sir Lewis

Casson came over to us and asked me

why I liked The Mastersingers.

"Would you like to hear some of it?"

I asked, hurrying them into the study

beside the Music Room, taking out a

record and playing the Overture. They

listened attentively, describing a performance

they had recently attended in Germany.

"The Bayreuth Festival is quite an

event. You must ask your father to take

you one day. Or you could listen to

the broadcasts on the radio, even if

it will be at some unholy hour here,

as it is broadcast live."

Daddy rescued them from my record playing,

promising we would all attend the Premiere

the following week, if it fitted in

with their schedule, which it did.

So, my first visit to the opera, accompanied

by my new friends, was all the more

exciting. Dame Sybil looked radiant,

and agreed with me that the tenor was

quite the most handsome man on earth.

Allan Ferris was his name, and he became

the object of my adoration. I pinned

his picture to my bedroom wall and kissed

it good night before I went to sleep

every single night. A pretty soprano,

Joy Tasman played Eva and I would have

loved to have been grown up and to have

been the character she played. It was

such a romantic story.

The stage set was to represent Germany

several hundred years ago, the singers

were costumed in gorgeous period costumes.

James Wilson sang the important role

of the blacksmith Hans Sachs. He had

broken his arm and wore it in a sling,

even if the libretto had no explanation

for it.

I knew every melody so well, each ensemble,

and now it was all assembled together

with acting and costumes, it was absolutely

fantastic. When the opera ended and

all the wonderful tunes I had learnt

had been played, I felt terribly sad

that the event I had waited for so eagerly,

was over. I wanted it to go on forever.

"May I come to another performance,

Daddy?" I asked.

"We'll see," he said, appropriately.

AN AUDITION

Then one day, unexpectedly, my stepmother

announced, "You are to be auditioned

this afternoon by the great Nadia

Boulanger. You are very lucky, for

she is a famous composer and pianist

who has one of the most prestigious

schools in Europe." Indeed not only

was she all these things, but I knew

my father and his sisters had worked

with her in London before I was born.

My heart sank. "I haven't practised

since we were on the boat on that awful

out-of-tune piano. You know I am not

very good, even when I work hard. It

will be a disgrace to Daddy. I don't

want to audition."

We went to Madame Boulanger's imposing

home by taxi. She was an ageless lady

of regal deportment who dressed like

a fashion model, yet possessed the most

friendly and gentle face I had ever

encountered. There was something about

the way she moved which suggested she

would be kind, her arms moving with

a fluidity, touching me softly on the

shoulder to guide me into the room.

She must have been in her late sixties

or early seventies. It was not what

she wore that I was impressed by, but

by the inner beauty which gave reassurance

that everything was going to be all

right.

"So this is la petite musicienne?"

she enquired, welcoming me, continuing

her conversation in rapid French which

I could not understand. She indicated

to Stepmother that she should wait in

the salon, and led me towards her music

room and bade me sit at the piano.

The room was not as beautiful as ours

had been in Sydney. It lacked colour,

its centrepiece an enormous Bösendorfer

Concert Grand, forbiddingly black and

threatening.

"Ma petite," she began, continuing

in English. "You will learn the language,

do not fear. Here all I need is to hear

how you play. First, a little sight-reading."

She brought out a bundle of immaculate

music sheets, such as we seldom saw

in Australia. I missed the dog-eared

music books to which I had grown lovingly

accustomed.

The first piece was by Jacques Ibert,

The Little White Donkey. A recent

examination piece, it was one of the

few pieces I had committed to memory.

If I played it now, as a sight-reading

test, Madame Boulanger might imagine

me to be proficient and gain false expectations.

My thoughts raced as if my head would

explode.

"I cannot do it. I cannot play the

piano. You see, my parents want

me to be good, like them, but I have

no talent. I really must go back home

to Sydney now. I would be useless to

you and a disgrace to my family. Please

understand." I could not restrain my

tears.

Madame Boulanger came and sat down

beside me on the piano stool, as my

friends used to when we turned pages

at each other's concerts. "Would you

not play just one piece for me? That

way, your mother, she could hear you

had tried. I could explain that my standards

were too demanding for one so young.

That would maybe save the situation."

I could have kissed her.

There was one movement of a Mozart

piano sonata, in C major which I knew

I could play passably well. I smiled

at her and launched into it, introducing

sufficient wrong notes to make even

this lovely music excruciating, laughing

as I did so. She put her hand on my

shoulder and gave it a squeeze.

"It will be our little secret," she

promised, stroking my hair and smiling

at me. "Leave it to me. Be happy somewhere,

my child," and we walked out into the

salon together.

"Madame Goossens, I am afraid, the

little one, she is not ready for my

school. A good child, but much too young.

Let her develop a little. We will say

au revoir. Perhaps we shall meet

again in a few years time."

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

A VISIT TO FATHER

AND A CONCERT - London

In 1957 I occasionally went to London

to visit my father and on one occasion

he particularly invited me to stay overnight

at his flat in St John’s Wood. He said:

"Stay the night and come to a concert

with me at the Royal Albert Hall. It's

the wonderful young German baritone,

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau. A

recital. Lieder. It's a stunning programme.

He'll be one of the world's greatest

singers in a few years. Come and be

part of that legend. I've been given

free seats by an old friend."

We had never paid for seats to concerts

before. The idea seemed odd now, that

Daddy should ever have to pay. I was

glad he had a friend who could let him

have free tickets.

"We shall eat at the Colonnade. It's

an old family hotel. The food is a bit

dreary, but it's reliable. They never

serve a bad meal. I have an account

there and I think you will like it.

We can get taxis around, save getting

cold on the Tube. You have a bit of

a cough, haven't you?" he enquired,

concern in his voice.

"I've had this cough for weeks, can't

seem to shake it off. All I need is

some sunshine." We smiled at each other

in agreement, as if we dreamed together

of Sydney again..

Daddy helped me into my student duffel

coat, second-hand from Oxfam. He pulled

down a woollen scarf from a peg in the

hall, went to put it around his neck,

then, lovingly, put it around mine instead.

I reached up and kissed him on both

cheeks, tears rolling down mine as I

did so. How could I possibly be cross

with him? He was certainly more sinned

against than sinning..

"This is all very strange, isn't it,

little one?" His voice reflected his

sadness and aloneness.

"Do you think we will be able to go

back to Australia soon?" I asked him.

"I've had a really bad time there.

I loved it and wanted to dedicate myself

to the new Opera House, you know the

site I wanted was finally chosen, but

they were taking so long to organise

it." He broke off from what he was saying,

looked as if he was thinking about something

else, and muttered sadly, almost to

himself, "I had thought people respected

me."

"Daddy, they did! You had so many friends

in the orchestra who adored you, and

your Diploma Students. Surely it will

be all right again soon. Surely people

don't change."

"Things happened which I don't want

to discuss, or to worry you about. But

I don't think I am going to be able

to go back there. Not for a long time,

anyway. You, my little one, would find

the atmosphere very changed."

"I'd like to know what happened, Daddy.

It would help me to understand what

you're going through."

"I'm no good at talking about personal

things. Leave it at that. Things will

work out."

……………

The Royal Albert Hall recital attracted

a full house. It was my first visit

to that beautiful theatre in the round,

although I knew my family had performed

there frequently for decades.

Unfortunately for me, Daddy's friend

had given us seats in the second row

centre, which brought us into immediate

view of the singer. This should have

been ideal, until my cough took a hold.

Once I began, I could not stop, using

Daddy's scarf to muffle the loudness,

almost choking with the effort of silencing

my barking sounds.

At interval, Daddy said we were going

to see Mr Fischer Dieskau.

As we walked in to see him in the Green

Room, he rushed forward and shook Daddy

by both hands.

"Sir Eugene, so kind of you to come

to my recital."

To my eternal mortification he turned

to me, "And this little lady, she is

your daughter, no? And with a very bad

cough." He smiled at me and addressed

me directly, "I will give you a pastille

to suck. It will help the soreness in

your throat."

He handed me a Zube, then changed his

mind and gave me the whole packet.

I was speechless with embarrassment,

then, remembering my manners said, "Forgive

me. Your wonderful recital is being

spoilt by my coughing. Would you prefer

that I did not return to the hall?"

He smiled, his young round face friendly

and enthusiastic, "The most important

thing for a singer, is to have an audience.

It is not your fault you have a cough.

Please go back to your seat now, and

forget your embarrassment."

He asked his pianist to fetch a glass

of water, gave it to me, and poured

himself some water, taking a separate

glass. I supposed he was afraid of catching

my germs.

The treatment must have worked, for

I did not cough even once during the

rest of the programme. At the end of

the performance, he came forward to

take a bow, and his special smile first

to my father and then to me is amongst

my most treasured memories.

© Renée

Goossens 2002

See

Book review by

Fred Blanks smh.com.au