Between 1871 and 1876 four major stage works

appeared in Europe, one each in Germany, Italy, France and Russia.

These works bear on each other in some remarkable ways. Each of

them has the same plot ó someone is being forced for reasons of

convention or patriotism to marry somebody they arenít in love

with. They arenít going for it, and the course of true love results

in most everybody being dead by end-curtain time. All four works

are today hailed as transcendent masterpieces in their forms,

but two of the four were failures in their first productions.

Three of the four works are set in the heroic past which tends

to give the theme a monumental, dare I say Biblical, dignity.

The other one was set in a foreign country, that is foreign to

the audience. In two of these works the hero has the same name.

This remarkable synchronised public assault by the artistic intelligentsia

from four different countries on conventional European marriage

customs eventually had its success in changing things around.

OK, has everybody got Aïda, Götterdämmerung,

Carmen ó and Swan Lake?

Perhaps, you say, Iím making too much of all

this. After all, Rossiniís Cambiale di Matrimonio of 1810

has a similar plot. Yes, but CdM was a comedy, nobody dies,

it was set in what was the present day, and it didnít, and wasnít

intended to, make audiences angry. And then Rossini turned around

and wrote La Gazza Ladra which has the opposite

message ó in troubled times trust in God and do what youíre told

and everything will come out all right.

* * *

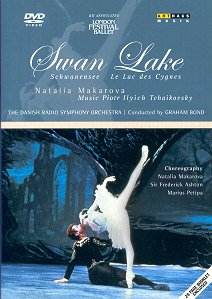

Although I was sufficiently impressed to have

a very good time, some reviewers who have seen many notable performances

of Swan Lake tend to find this performance lacklustre.

Although in the earlier scenes there seems to be a lot of unaffected

walking about on stage, there is some exceptionally fine ensemble

dancing here and there, especially in the classical swanlet corps-de-ballet

scenes. The four "little swans" are absolutely stunning.

For me the star is really Martin James (Benno) who projects a

rugged masculine persona, the sort of guy you really would like

to go hunting with, who really likes dancing with girls. Peter

Schaufuss (Prince Siegfried), who could be replaced by a hydraulic

lift on wheels, since his main function seems mostly to be carrying

the prima ballerina around on stage, is, except for his few terrific

solos, rather pale by comparison. Prima Evelyn Hart has

some superb dancing moments; she is a good actress and makes a

very evil Odile, as well as a very heartbroken, forgiving Odette.

Johnny Eliasen as Rothbart is really scary on stage during the

ballroom scene, where everybody is enchanted and apparently sees

nothing wrong in the prospective father-in-law being all made

out of lead, having no head and waving a twelve foot wingspan.

The rest of the time heís replaced in the video by ghostly owl-like

projections that are a little over-done. The sets are relatively

simple, using rear projections and overall colour changes to shape

mood. The use in the final scene of Ďmistí and blue laser projection

is very effective in creating the impression of the lake water

rising over the stage and drowning the lovers. Although some Ashton

choreography is used, they donít use his Ďhappy endingí where

the swanlets attack and destroy Rothbart and save the loversí

lives. This is the traditional ending where after they drown they

move up into the sky and disappear into the moon.

Comic relief is provided by Natalia Makarova

reciting what is apparently a Cyrillic phonetic transcription

of a summary of the story in English. Nobody could have that heavy

an accent and know a single word of English. If your children

donít behave, you can threaten to make them watch and listen to

her again.

The musical performance is as good as any Iíve

heard, avoiding the rushed tempos which often ruin this music

in concert performances. The sound is 2.0 stereo, very clear and

rich sounding with good bass, but I heard nothing from the rear

channels. The string ensemble is razor sharp, the high and low

percussion, so important to this score, are clearly present but

not obtrusive. The picture is about as clear as film, but definitely

not high resolution video. The complete score has 29 numbers;

Antal Dorati with the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra takes 131.45,

André Previn, with the London Symphony Orchestra, 155.38.

This performance is substantially complete at 111.10, only some

repeats and some of the national dances in the ballroom scene

have been cut. But of course the Neapolitan Dance is there, near

the beginning of the scene, to serve as a dashing showpiece for

Martin James.

Paul Shoemaker