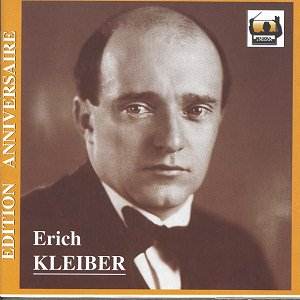

Erich Kleiber left for Montevideo in June 1939. Heíd

resigned his position at the Berlin Staatsoper in 1934, refusing all

entreaties to return, and began a peripatetic life which eventually

led him to South America. One of the more interesting stops was the

Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto with Mischa Elman in Havana Ė and a number

of his Buenos Aires performances have in fact survived in the archives.

After the War he remained to complete his concert engagements in South

America before moving north to conduct the NBC Symphony, performances

presented in this Tahra tenth anniversary edition.

Of the great conductors active in Berlin in its Weimar

glory Kleiber was the one least captured in the recording studios. The

rupture of the 1930s and his wandering career in South America have

equally served to emphasise the somewhat shapeless and haphazard nature

of his discography Ė an idiosyncratic one that has been fortunately

swelled by extant broadcast performances. Hartmannís Sixth Symphony

for example survives in two versions, from Berlin and Munich, both from

1955 as does a work as unlikely as Novakís South Bohemian Suite (Prague

1956) Ė though it should never be forgotten that Kleiber had lived in

Prague as a child. He was also a staunch proponent

and supporter of contemporary composers and in addition to Hartmann,

performances of Bittner, Schoenberg, JanŠček, Busoni and Korngold

have survived. He first recorded for Vox in 1923, switching to Polydor

in 1926. Heíd clocked up a hardly negligible series of discs

to his credit by the time he was forced to leave Germany.

Tahraís tenth anniversary series of vignette single

discs devoted to the works of individual conductors aptly turns its

focus on Kleiber and his post-War NBC performances of 1946 and 1948.

Berenice, complete with piano continuo I think, opens in very grand

fashion. The NBC strings are burnished with massive, staunch basses

all to the fore in Kleiberís epic conception. He is not afraid to indulge

some truly intense diminuendi either. The Schubert comes from the same

concert. Kleiber gives a real fillip to the strings in the opening movement.

The woodwind have a very individual tonality to their sound. The principal

clarinet has a rather blanched tone and the oboe a centralized, unluxuriant

one, all of which imparts a rather cool and aloof patina to their contributions.

The sound is a trifle congested and tends to emphasise the loose ends

in the playing, of which there are a number. But at Kleiberís wittily

inflected tempo, over pizzicato accompaniment, the Allegretto comes

over as droll and the succeeding Minuet a delicious feature for oboe

and bassoon amongst other felicities. The finale is expertly fleet and

exciting. The Tchaikovsky comes from a concert on 3rd January

1948. The composer was hardly an interest of Toscaniniís but Kleiber

certainly didnít share the Italianís indifference or hostility and nor

did Toscaniniís despised sometime co-conductor of the NBC, Leopold Stokowski.

Thereís excitement in Kleiberís Fourth but also plenty of orchestral

clarity. He gives the folk-inflected passage for clarinet and flute

from 5í02 a certain deadpan elegance. He can be stern yet yielding when

necessary. Some mushiness intrudes on the acetates in this movement

however, especially on string forte passages from 14í30 onwards and

there are moments of negligible, but audible, radio interference. The

close of the movement brings an impressed burst of applause. Scuffs

and acetate chugs attend the second movement. I admired the linearity

of Kleiberís conducting here and the intensely emphatic string moulding,

especially the passage from 1í29 to 1í32 and its analogue in the wind

choir. Indeed the fluency and strength of the Scherzo and Finale are

testament to Kleiberís dynamism and orchestral mastery. Thereís nothing

over lingering about his interpretation; it obeys the proprieties with

expressive tautness.

Imperfections aside, and they wonít really concern

any but the most fastidious, Kleiberís discography is one of the more

precious souvenirs of a generation of conductors whose lives were punctured

by politics and War.

Jonathan Woolf