Lilburn’s death in June 2001 coincided with the latest recordings

of the three symphonies, rightly characterised as the heart of his creative

work, and music of the most impressive cast. The First Symphony dates

from 1949 and was premiered two years later. If the North Island of New

Zealand was his paradisiacal home and his studies with Vaughan Williams

gave structure to his symphonic thought, the First is a work that reflects

both influences – that of nature and the musical means by which its immensity

and beauty can most properly be conveyed symphonically. The result is

a symphony of power, mystery, delight, structural sagacity, sure pacing

and gathers up its fairly clear lineage – Vaughan Williams himself, Sibelius

– into a cohesive narrative.

Opening with a trumpet fanfare motto and a sense –

ever present in Lilburn - of prescience and anticipation the opening

movement passes through reflective stasis, the return of that craggy

motto theme and the sense of the immensity of space. The Sibelian analogies

are unavoidable I suppose but what is rewarding about Lilburn is his

mastery – even in this relatively early work – of symphonic thought,

of reiteration, of the use of silence and reflection, of never becoming

bogged down. His string writing is variously austere and soaring – or

both – and the way in which themes return reinforced, swollen and teeming

with new life is especially exciting. At 7’48 sonorous strings and sinuous

cor anglais saturate the narrative only to dissolve again; when that

trumpet figure returns we sense the length of the distance come. The

second movement opens out with stirring violins and brass fanfare responses.

The symphonic line of his argument is engineered by myriad little details

– quirks of orchestration, extreme attention to single line woodwind,

the twisting lines of the strings, the effective and insistent use of

brass paragraphal points, all of which convey colour and meaning. The

end of the movement is visited by a kind of Tallis theme, modal and

becalmed and essentially noble. Over rumbling, ominous lower strings

a sense of open air and warm-hearted freedom is gradually generated.

Those pervasive fanfares have now mutated and are fulsome and grandly

affirmative and grow in amplitude and confidence. At 7’40 a serious,

cello resonant theme of mellow beauty courses through the music which

rises up to the flourish of a final fanfare of unbridled power.

The Second Symphony, completed 1951 but only first

performed in 1959, is in four movements. Once more Lilburn is expert

at conveying a sense of symphonic expectancy – with the rise and fall

of the argument flecked and haunted by oboe and horn passages and strings

barely concealing their striving for momentum. Some eruptive passages

lead a flute solo – static, pregnant with meaning – before the serious

sounding trumpet and string peroration moves in a cantilever to include

wind and horn reminiscences, internalised and absorbed, in the final

page. Lilburn’s music has often been held to be a kind of pictorialism,

reflective of the peaks and valleys of New Zealand’s landscape – I’m

sure this is so, but what runs through this writing is a superb grip

on architecture and a sense of structure and form compelling entirely

on its own terms; lovers of Sibelius and Tubin will be welcome in this

landscape. The invigorating freshness of the Scherzo reminds me of nothing

less than Peggy Glanville-Hick’s Etruscan Concerto – herself another

Vaughan Williams pupil - the same exultant prairie freedom runs through

it though not one quite as ebullient as the Australian composer’s. Nevertheless

nimble and quick witted strings scintillate and the rather American

sounding writing is cut short at 3’02 by the central panel of the movement,

a long breathed, "long bow" melody with decorative roulades

pirouetting around it. A magnificent, life affirming and joyful movement

– stop whatever you are doing and listen to it now. In contrast the

slow movement is eloquent and unselfconscious, again long breathed but

this time a little pertinently aloof. The Finale is fresh and melodically

attractive with punchy trumpets, sylvan flutes, stern lower brass and

rather philosophical-reflective strings which leads to some fugal writing

but ends in torrents of almost ecstatic simplicity and lyricism.

The Third of Lilburn’s symphonies is a one-movement

fifteen-minute work composed in 1961, premiered the following year and

first recorded in 1968. In five connected episodes this is a tense,

complex, avowedly modern work with much use of entwined wind and brass

blocks. After 6’55 brass fanfares – a distinctive feature of Lilburn’s

writing whatever the stylistic imperatives – and scurrying strings create

a sense of imminence, immediately undercut by the bassoon and by a sense

of dissipated momentum. Lilburn’s adoption of a highly personalised

use of serial technique never subordinates the orchestral material;

his recognisable traits are ever present though suitably condensed here.

The fourth episode in which the solo trumpet leads on to an ominous

build up of material – laconically noted by Lilburn as "concerned

with some dialogue for brass" – is impressive not least for its

superb handling of short motifs and blocks of material. The "fragmented

coda" that Lilburn notes is a species of analytic terseness and

ends the symphony on a note of ambiguity and unresolved complexity.

This is a work that demands concentrated and repeated hearing; it wears

its learning lightly but presents a carapace that is sometimes forbidding

and stern.

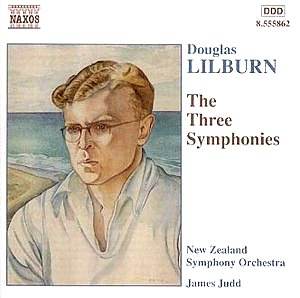

These works have been recorded before. With the same

orchestra John Hopkins has recorded all three (Continuum CCD1069), Ashley

Keenan recorded No 2 in 1975 – coupled with Hopkins’ First and Third

(it was Hopkins who was both dedicatee of the Third and who first recorded

it). Doubtless others are around but this new set, with the impressive

James Judd is a major achievement in its own right. The New Zealand

Symphony Orchestra play with sensitivity, judicious weight and technical

expertise and Judd is an affectionate and strongly engaged Lilburn conductor.

Tremendous sound as well – an excellent disc in every way and a first

port of call for those who want to get to know these splendid symphonies.

Jonathan Woolf

Information received

Mr Woolf claims that Douglas

Lilburn's Second Symphony was not given its

first performance until 1959, although written

in 1951. This refers only to *concert* performances,

but it was given at least three broadcast

performances before then:

The first performance was given by the NZBCSO

under Warwick Braithwaite in December 1953

(YC network). The second performance was by

my late husband Georg Tintner, with the NZBCSO,

broadcast on 14 December 1954. He also gave

the first Australian performance of the work

with the Sydney Symphony Orchestra in a broadcast

on 7 April 1955.

A tape of the Braithwaite performance is held

at Radio New Zealand Archives, as is a tape

of a performance my husband conducted, which

is undated; it could be either the 1954 broadcast

or the broadcast (with NZBCSO) of 16 August

1964.

Tanya Tintner

Also see review

by Neil Horner