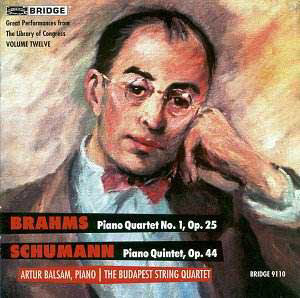

A portrait of Artur Balsam stares from the cover of

Volume 12 in Bridge’s series of live performances from the Coolidge

Auditorium of The Library of Congress. He had first joined the Quartet

for a performance in 1946 and it was in 1951 that he rejoined them,

and again in 1953, the results of which collaboration are preserved

here (the other piece played that day in 1951 was the Shostakovich Piano

Quintet Op 57 – which I hope will make a future appearance in the series).

Balsam was active as an accompanist at the Library

– a recital with Nathan Milstein is on Bridge 9066 and in the Brahms

Op 108 I found some of his rhythmic license rather idiosyncratically

disturbing. Here however in Brahms’s G Minor Piano Quartet I find him

a much more congenial proposition and he joins with the Quartet in a

big-boned, muscular reading, leonine and powerful that grips from the

start of its not inconsiderable length. Heretical though it may be I

have increasingly come to believe that the Budapest’s greatest strength

lay in the central to late Romantic repertoire and that their Beethoven,

though often rising to great eloquence, is sometimes compromised by

moments of slickness and manicured phrasing. Bold, declamatory but well

scaled, the Brahms emerges as a powerful creation. Balsam is very slightly

backward in the balance but he is by no means subservient in the ensemble

and contributes his share – and more – to a driving and sensitive performance.

The Allegro opens with purposeful intent; the Intermezzo second movement

brings lightness and inflection from the string players Roisman, Kroyt

and Mischa Schneider, the slow movement has all the requisite depth

of tone required and the finale bursts into life with its contrastive

properties of alla zingarese abandon and noble restraint.

The Schumann is more a known quantity because the Quartet

recorded it twice. They had recently set it down, two years earlier,

with Clifford Curzon and were to record it again a decade or so later

after this Library of Congress performance with a very different kind

of pianist, Rudolf Serkin. As Harris Goldsmith, the once more excellent

annotator, asserts the temperamental qualities of these two recordings

are reflective of the pianists’ musical natures; the Curzon is more

lyrical and yielding, the Serkin more pungent and antagonistic. Balsam

lacks little in drive and conviction but he is fully alert to the pliancy

of the second movement and its poco largamente instruction. They

don’t play the first movement exposition repeat but do display real

drive here and an affecting but somewhat aloof feeling in the slow movement.

Staunchness and vigour attend the Scherzo and a sensible tempo in the

finale. With Jac Gorodetzky as second violinists the Budapest’s ensemble

is tempered by his Gallic affinities and in Balsam they had a worthy

partner. This is a good performance but not the equal of the Brahms.

Plenty to savour for the Quartet’s admirers and to

hope that there are many more such delights in the vaults to keep us

enriched in the years to come.

Jonathan Woolf