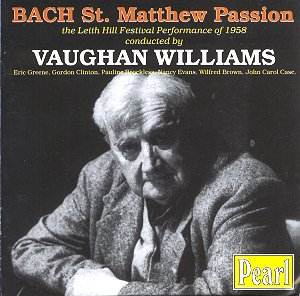

It’s impossible to overstate the significance of this

recording. Taped in 1958 five months before Vaughan Williams’ death,

it preserves a performance given at that year’s Leith Hill Festival

of a work he had conducted there since 1931. The recording was made

by Christopher Finzi and Noel Taylor and is of perfectly acceptable

quality - clear, unobtrusive, not expansive but given the semi-amateur

circumstances, good. Certainly it enshrines a relatively unusual musical

occurrence – affording us the experience of hearing one composer conducting

the work of another. More than that it incarnates a performance practice

and a personal response to Bach both profoundly of its time and yet

movingly transcendent of stylistic change.

Of course there are necessary points to note. Vaughan

Williams cut a dozen numbers, including four arias; the edition used

is the Elgar-Atkins, sung in English; the keyboard continuo comprises

organ and piano; the chorus is very large. The booklet notes – comprehensive

and thoughtful, by Jerrold Northrop Moore – quote Vaughan Williams’

views on the practicalities of modern orchestral resources and their

implementation as being, in a sense, a tribute to Bach himself - as

well as outlining his rationale for the exclusion of certain numbers.

He also spoke of it being wrong to include everything for the sake of

"mechanical completeness." Other small but telling details

emerge; how Vaughan Williams insisted the audience stand for the Last

Supper Scene and, whilst his beat was imprecise, how he stared at the

musicians over the top of his glasses.

The performance itself is extraordinary. Firmly accented,

the choral singing is generally massive and slow with the recitatives

equally slow in tempo. Rallentandos abound, as do accelerandos to heighten

dramatic impulse. The result is not heaviness and ponderousness but

an organic and fiercely dramatic realisation of the meaning of the score.

And one I have to say I found intensely moving. It needs to be noted

nevertheless that the Dorking Halls’ acoustic doesn’t flatter the soloists

– clear it might be but there’s no comforting cushion around the voices.

Eric Greene is the Evangelist - textually accurate with, despite the

slowness of his recitatives, a remarkable instinct and understanding

of the music’s contours. What can’t be denied is that by this stage

of his career his voice – especially unaided by the generally unsympathetic

acoustic – was coming under very considerable strain. He is very sorely

tried at the top of his compass in Now when Jesus, as, it must

be admitted, elsewhere. Wilfred Brown employs his very distinctive musical

intelligence in his arias – listen especially to his softened tone rising

and falling in O grief! that bows and to his singing of I

would beside my Lord with the sinuous oboe line behind him.

Nancy Evans is precise in articulation of consonants in Break in

grief – attractive but not overwhelming. The choir itself is excellently

trained, sibilants precisely enunciated, reflective, reverential or

passionately involved in the drama it is itself evoking. Under Vaughan

Williams’ direction the work emerges as an intensely dramatic and fluid

one, a performance powerfully responsive to the text and to the dictates

of its internal and external meaning. It is a remarkable document and

I strongly urge you to hear it.

Jonathan Woolf