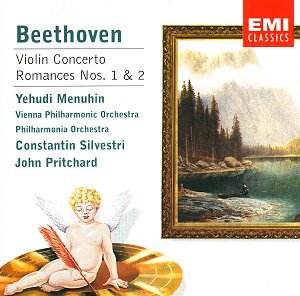

I encountered the F major Romance in a curious Menuhin

compilation not long ago and remarked that the Viennese classical masters

must have written their music all along in the knowledge that one day

Menuhin would arrive to play it with this pure, noble tone, simple yet

somehow pregnant with spiritual feeling. This Romance is the highlight

of the disc, at least for me. The G major Romance starts with a slight

disagreement with the conductor over the tempo and remains a little

heavy in effect. Is F major more suited to Menuhinís spiritual depths

than the brighter G major? I now feel I must give voice to a question

which I was prepared to set aside during the F major. Though all performances

known to me adopt tempi similar to those here, they are Romances not

Meditations, they were fairly early pieces written for an Italian violinist

and in both cases Beethovenís time signature is 2/2 not 4/4. Do they

really have to be so slow? The problem is that, while in the melodic

moments you can get away with it, especially if you have a tone like

Menuhinís, there are many moments where the violinist is compelled to

play simple scale passages fairly slowly and try to give them a meaning

when perhaps they are only intended to be thrown off brilliantly. I

know Menuhin could make a spiritual journey of the scale of C major,

but all the same enough is enough, especially if you have the two together,

and Iíd dearly like to hear some violinist reassess the whole approach.

Another movement that is often taken at a funereal

pace is the first movement of the violin concerto. Itís true that Beethoven

wrote "Allegro ma non troppo", and this time the time signature

is 4/4 not 2/2. However, Menuhin would appear to agree that a certain

mobility and impetuousness, more than we generally hear today, is required.

The conductor seems less convinced.

There have been some odd concerto partnerships over

the years, a fair amount of them from EMI. Constantin Silvestri (1913-1969)

was a Romanian conductor noted for his virtuoso control of the orchestra

and a freely rhapsodic style of interpretation deriving from a wide

palette of orchestral colours. Thus far he may seem to resemble his

compatriot Sergiu Celibidache; however, in comparison with that wayward

giant, his art, however brilliant, lay on the surface and I never heard

it suggested that any deep spiritual qualities lay behind it. His major

achievement may have been, more than his actual performances, his work

with the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra which he raised to international

heights, creating a domino effect among the British provincial orchestras

by his demonstration that good orchestral standards were not limited

to London. He was not noted for his Beethoven and so, on the face of

it, there seemed little point in carting Menuhin to Vienna to have him

play under a conductor who was not likely to bring out the unique qualities

of the orchestra. At around the same time Menuhin recorded a Brahms

concerto in Berlin under Rudolf Kempe. Surely this conductor, or Carl

Schuricht, who recorded for EMI in the 1960s in Vienna, would have been

more inspired choices. Or else stay in London and do it with Klemperer,

Boult or Barbirolli (only six years later he recorded the work with

Klemperer and the New Philharmonia).

Still, Silvestri was a fine musician and the opening

tutti goes with a certain majestic dignity. Menuhinís tone as

recorded in Vienna seems more brilliant than in the Romances and he

also quite often plays sharp. At times this is enough to raise eyebrows

Ė take the exchanges with the clarinet at the beginning of the Larghetto

Ė at others it is barely perceptible. It contributes to the impression

that he was in an impetuous frame of mind, for the passage-work which

many Ė signally Menuhin himself on other occasions Ė invest with much

inner meaning, is made passionately exciting. All this means that Menuhin

moves Silvestriís tempo on, sometimes considerably. So the tempi swing

back and forth between them until, in the later stages of the development,

Silvestri realises he isnít going to get it his way and starts to collaborate.

Beginning perhaps from the famous G minor episode, which is serene yet

still mobile, there is much fine work here.

In the slow movement Menuhin seems again restless at

the beginning, but this time it is he who settles into Silvestriís warmly

romantic backdrop. Again, the later stages of the movement are the best,

with a deeply felt, expressively inflected yet still mobile interpretation

of the "sul G e D" variation.

In the finale it is the violinist who gives the tempo,

yet Menuhin himself often seems to want to move away from the relatively

grave enunciation of the rondo theme, to which he always returns. As

the years went on (I am remembering a performance in Edinburgh in about

1974) his enunciation of the rondo theme got graver and graver, while

his tendency to run away with the passage work in this movement got

more pronounced too. Here the process is only just beginning and this

is perhaps the most successful movement.

This performance is undoubtedly the work of a great

violinist, but is not quite a great performance. If you canít take the

"historical" sound of the versions he made with Furtwängler

(Lucerne Festival Orchestra 1947, Philharmonia 1953) and if you find

Klemperer a rather coldly magisterial partner, you might try this, certainly

in preference to the 1981 version with Kurt Masur (Leipzig Gewandhaus)

which documents his more problematic later years. Apart from various

bootleg editions which have been around, one official live performance

has entered the lists Ė that conducted by his fellow violinist David

Oistrakh (1963 with the Moscow Philharmonic in London, on BBC Legends)

. But part of the fascination of Menuhin was his combination of spirituality

and fallibility, and to that extent all his recordings are essential.

Christopher Howell