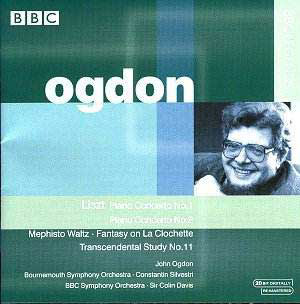

Thirteen years have passed since the untimely death in 1989 of John

Ogdon at the age of 52, but none who experienced his special blend of

musical insight and technical brilliance will ever forget him. I last

heard him ‘live’ in the mid-1980s. By then, he had recovered sufficiently

from the dreadful affliction which had brought his dazzling career to

a sudden halt in 1973 to enable him to embark on a limited concert schedule.

Characteristically, it was not an old warhorse that he played on that

occasion, but the Second Piano Concerto of Alan Rawsthorne. True,

some of his old fire had deserted him, but he had lost none of his unique

charisma – I particularly recall the affection which he lavished on this

fine work. (A further reason for remembering this concert was that, if

my memory serves correctly, Sir Charles Groves was the conductor: another

musician notable for championing unfashionable causes.)

So, this disc, which captures Ogdon at the height of

his powers, is to be treasured – especially since none of the tracks

emanates from a recording studio. Liszt, I suppose, is still a controversial

composer: for some, a deep musical thinker; for others, a bombastic

showman. Ogdon’s supreme virtue was his ability to reconcile these poles

of opinion. This is best illustrated in his explosive account of the

Mephisto Waltz no 1, where he combines amazing virtuosity with

seamless structural mastery. He also revels in the grotesque figurations

and harmonic distortions of La Campanella. Harmonies du Soir

is technically even more demanding: here, Ogdon sails through majestically:

he takes risks, almost all of which he surmounts.

Of the two concertos recorded here, I prefer the first.

In both, Ogdon’s command of filigree passage-work, bold declamation,

tender musings and – a particular characteristic – electrifying glissandi

flourishes are equally in evidence. And structural momentum is firmly

maintained throughout. The difference lies in the accompaniments. Both

conductors are in total sympathy with the soloist, but the Bournemouth’s

generally warm if a little ‘boxy’ sound is distinctly superior to that

of the BBCSO, which is unfocused and marred by coarse brass. Nevertheless,

unreservedly recommended.

Adrian Smith

|

![]() See

what else is on offer

See

what else is on offer