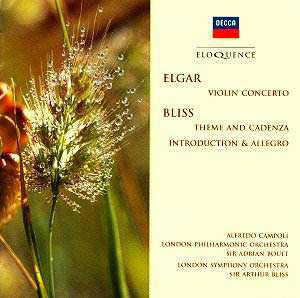

The Elgar Concerto has fared well on disc. There are

very few poor performances and a number that have, on their own terms,

real merit. At the peak stands the Sammons Ė newly reissued on Naxos

Ė and it will be interesting to see if this latest appearance deals

with the persistent pitch transfer problems that have bedevilled its

various incarnations. Somewhat hors de combat is the Menuhin-Elgar.

Hugh Beanís performance is profoundly attractive as is this Campoli

reissue, which dates from 1955 and is one of the most outstanding recordings

ever made of the concerto.

Though the sound can be a little papery in places nothing

can dim the masterly exposition of the orchestral introduction by Boult,

a far more eloquent traversal than those he was able to offer the disappointing

Menuhin, in his second recording, or the impossibly sluggish Ida Haendel.

He is especially successful at bringing out the wind writing, superbly

weighted and proportionate to the orchestral canvas, and each sectional

incident is blazingly well realised. Campoliís entrance is reflective

but not over lingering in the modern manner and which can be so disruptive

to the syntax of the musical argument. He employs some judicious expressive

devices to heighten his playing. At 6í00 the orchestral counter theme

to his solo line is movingly audible even at Campoliís slowing tempo

Ė compare and contrast with such as Nigel Kennedy where the necessary

backbone is entirely missing and nonsense is made of Elgarís orchestration.

Campoli makes the most elegant and apposite of slides at 11í01 Ė quick,

lyrical, with just the right weight and speed. Boultís control of orchestral

dynamics from 14í30 Ė readying for the subsequent orchestral outburst

Ė is but one example of his elevated level of conducting. Campoliís

passagework comes under a little strain here and at 16í15 I felt the

imposed strain by Campoli to be a little forced and impeding to the

flow toward the summit of the movement. He just doesnít sweep forward

enough. But it is an internally consistent view of the movement and

one that commands respect.

The slow movement is deeply expressive and fluent;

it tends to show up performances (such as, say, Heifetzís), which fail

to maintain a proper balance between momentum and expressivity. Campoliís

tone is ardent without over emoting. The finale is of a piece with the

other movements; Boultís conducting is alert and sympathetic and Campoliís

surmounting of the fiendish technical demands - which is not, in truth,

absolute - is still outstandingly good. Itís only when one compares

Campoli with Sammons that the breathtaking control of the latter makes

Campoli seem just a little staid. There is again not the onward rush

and sweep of the Sammons performance; there is not the sense of an unstoppable

momentum, the big tone leading a galvanized orchestra to the final triumphant

chords. Nevertheless this is a most distinguished recording; putting

aside Sammons and Menuhin it is my preferred choice, just ahead of Bean,

and I can pay Campoli no greater compliment than to say that his tonal

beauty, his awareness of structure and the dictates of architectural

compromise, are of the highest quality and this performance is testament

to his stature as a great violinist.

The coupling is cannily chosen given Campoliís close

association with Arthur Bliss. He was the dedicatee of the Violin concerto,

which he recorded and of which he gave some famous Russian performances

on tour with the composer. The Theme and cadenza for solo violin and

orchestra is a lyrical and beautifully played piece derived from incidental

music composed for a 1945 BBC production of a radio play by Blissí wife,

Trudy. Bliss also conducts an infectious performance of his 1926 Introduction

and Allegro (revised 1937), composed for Stokowskiís Philadelphians.

Bustling, inventive, rhythmically propulsive with superb wind writing

and juddering strings it makes a resounding finale to a significant

and unreservedly recommendable disc.

Jonathan Woolf

![]() See

what else is on offer

See

what else is on offer