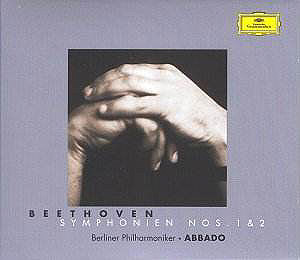

Rarely can a CD cover have reflected its contents so

cleverly or accurately. Abbado’s hands are clasped in mono relief while

his face is hidden: surely a conscious retort to the Berlin Philharmonic’s

last DG Beethoven cycle, the frontispiece of which boasts a side profile

of the aged Herbert von Karajan, gold and silver beams radiating from

the maestro’s head. Without trying to stretch the photographic metaphor,

this faceless cover says: ‘Forget about me. Listen to Beethoven’. Of

course, the image is as carefully placed and manipulated as its earlier

correspondent, but at least Karajan showed a sort of brazen honesty

about the management of his image.

For what we have here is not Abbado as audiences have

known him up until the last two or three years, nor indeed the Abbado

of the grand, rich cycle he recorded in the ’80s with the Vienna Phil

(from which the 6th, 7th and 9th are

still well worth pulling from the shelves). For whatever reason, tempi

are fleeter than before, textures lighter, accents more marked and phrasing

less legato, more piquant. Add to this some staggeringly disciplined

playing from members of the Berlin Philharmonic, who stretch even their

reputation for collective virtuosity (a nasty moment for the strings

in the bars just prior to the recapitulation of no.2’s first movement

being excepted). Oboe and flute lines in particular give constant joy

in the intelligence of their phrasing and dynamic shading.

These readings are entirely literal, in the best and

worst senses of that word. Everything that could be gleaned from the

score is there; and very little else is. If you resent an interpreter’s

character as intrusive interpolation, then this is the Beethoven for

you. But what is the point of being able to hear every chugging semiquaver

in the Introduction to the Second’s opening allegro if they do not,

by their repetition, build up tension to be released by the allegro’s

soaring main theme? Where is the abandon which belongs to the trumpet

peroration in the coda of that movement, which Harnoncourt unleashes

so gloriously? Just as surely as joy belongs to the finale of the Ninth,

so should manic high spirits infuse that of the Second: what I hear

is slightly ill-tempered precision. Paradoxically, Abbado has paid conspicuous

homage to the traditional idea of the Second as descended from the Mozartian

symphonic ideal in its first three movements; just where this is most

obvious, in its opera buffo-like repartee between winds and strings,

he refuses to let them sing or tip knowing phrasal winks in true Mozartian

fashion. All the dotted phrases of the slow movement die away with perfect

period manners while lacking the elegance and delicacy usually associated

with the device. If this and others like it have been appropriated from

historically informed performance practice of recent years (as the booklet

baldly asserts: if you’re interested in why I believe this to be fallacious,

please refer to the review of this cycle’s nos.7 and 8) then they do

not yet sit entirely comfortably within the orchestra’s own distinguished

‘performance practice’.

Just as the Second has gained a Mozartian template,

so the First is generally reckoned to show Beethoven taking his cue

from the ‘Father of the Symphony’ and indeed I can’t remember having

heard a more Haydnesque performance of it. The plain-spoken slow introduction

conveys no sense of the musical confusion which pervades its key structure

(the music asks ‘Am I in C major? Really?’) and when it unobtrusively

arrives, the allegro bounces along charmingly. Abbado exploits the music’s

possibilities for Rossinian fun (as well he might, given his talent

in this direction) as did Ferenc Fricsay in another Berlin Phil recording.

The comparison lets Abbado down at the climax, where Fricsay points

the bass answers to the orchestral chords – as answers, not as detached

notes.

I wish I could be more enthusiastic about the overall

effect of Abbado’s scrupulous care over Jonathan del Mar’s new editions.

For in the process of weighting each chord and rehearsing every string

skirl, he seems to have lost sight of each symphony’s character. Maybe

it’s an old-fashioned concept, the canon of Beethoven symphonies each

with their own expressive world; Abbado clearly doesn’t have much time

for it. Plenty of other modern conductors, likewise self-consciously

unencumbered by the weight of tradition, do; you might not expect the

Royal Liverpool Philharmonic to offer serious competition to their colleagues

in Berlin but only hear them under Sir Charles Mackerras on EMI and

you will encounter a lithe young Beethoven with wit and profundity in

equal measure.

Peter Quantrill

![]() See

what else is on offer

See

what else is on offer