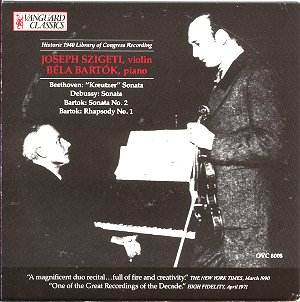

One of a number of remarkably preserved concerts at

the Library of Congress this recital is one of the most distinguished

and important of CDs. It contains the entire recital of 13th

April 1940 given by Szigeti and Bartók under the auspices of

the Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge Festival. If our understanding and knowledge

of Szigeti’s art is not radically altered nevertheless the musico-aesthetic

complexities of his partnership with Bartók are rich and the

light it shines on Bartók’s pianism is fundamental. The two musicians

had given recitals together since the mid-1920s – in Budapest, Berlin,

London, Oxford, Paris, Rome and New York. Both had recently emigrated

to America – though Bartók was to make one final trip home –

and were central members of the Hungarian intellectual diaspora. The

bulk of Bartók’s recordings were collected by Hungaroton but

as the notes aver his status as a composer has always – even in his

own lifetime – eclipsed his prominence as a pianist. He was widely active

as a piano soloist however and this Washington concert is one of the

most precious documents of his playing.

Szigeti’s opening flourish of the Kreutzer Sonata is

dramatic and very slow whilst Bartók’s first entry shows one

consistent feature of his playing – and many other pianists of an earlier

generation – that of breaking his chords by playing the left hand fractionally

before the right. When Szigeti joins there is some noticeable roughness

in his tone but by 5’28 there is a lightly treading ease of execution,

Bartók’s left hand correspondingly delicate, Szigeti gradually

lightening his tone. At 7’10 there is a tremendously emphatic episode

from Bartók with a sense of overwhelming and evolving drama emanating

from both performers. Szigeti is adept at thinning his tone in the interest

of tonal contrast to such an extent that we can hear the traces of his

oscillatory vibrato. The pizzicato episode launches a "struggle

and resolution" passage and this is emblematic of the performance

as a whole – it is a ceaselessly imaginative but powerfully projected

dramatic canvas. In the slow movement Bartók begins by rolling

his chords – an expressive device he employs to noticeable effect -

and observe some considerable dynamic gradients. His introductory passage

is therefore marked by peaks and troughs in the syntax with heavily

accented paragraphs. Szigeti’s sometimes rather dry tone does thin now

and then though it’s constantly illuminated by quicksilver phrasing.

At the grand restatement by the piano (again unsynchronised hands by

Bartók) there is an almost operatically introspective depth to

the playing – and Szigeti’s attacking note at 9’49 has to be heard to

be believed; I’ve never heard such a devastatingly wild moment from

him on record. I found it constantly illuminating to listen to the violinist’s

pervasive portamenti here – they are very precise and discreet and never

decorative or ornamental but rather almost emotional-structural in effect.

The finale begins as something of a divertimento after the sturm und

drang of the first two movements. Bartók’s runs here are noteworthy

as is Szigeti’s eloquent phrasing at 2’47 et seq. Both musicians coordinate

dramatically reduced dynamics here before opening out with sharply attacked

and accented playing. It’s true that Szigeti’s technique comes under

considerable pressure two thirds of the way through but against that

there are tremendous individual subtleties of rubato, rolled and broken

chords and articulation to admire in a performance that overwhelmingly

explores the dramatic impulses of this peak of the Concertante literature.

The little Bartók Rhapsody features some pellucid

playing from Szigeti and gleaming Bartok right hand articulation in

the first movement marked Lassu. The transformative second, with

its array of folk song influences and the uncanny resemblance to the

Shaker song Simple Gifts, has surely seldom received such a delicious

performance, one which blends simplicity with acute intellectual and

structural awareness. The Second Sonata was premiered in London by Bartók

and Jelly d’Aranyi in May 1922. He and Szigeti performed it often and

Szigeti noted in his autobiography With Strings Attached that

he and the composer made a point of playing it at all their recitals.

One reason was presumably its complexity and difficulty that has meant

that the work is resistant to easy analysis. It goes without saying

that its contours are delineated with clarity and meticulous understanding.

Szigeti is guilty of some bouncing bow in the first movement but in

the Allegretto Bartók’s percussive left hand incites his partner

to playing of the highest acuity. At 3’40 Bartók plays the slowing

pulse with almost hypnotic intensity and Szigeti’s folk fiddle episode

is fiendishly convincing. The monumental conclusion, with Bartók’s

piano cascading and Szigeti fiddling very high up, is a dramatic end

to a traversal that embodies the intense collaboration of performer-composer

and dedicated interpreter. The other work recorded that day was the

Debussy Sonata. Szigeti hasn’t the tonal opulence and sensuality of

Thibaud here; his tone is much thinner but his sensitivity is no less

involving. Bartók is rhythmically alive and constantly illuminating

– it may come as a surprise to realise that he considered Bach, Beethoven

and Debussy as the three composers from whom he learned the most. There

is a living grandeur to the playing and in the Intermède febrile

Bartókian piano and delicious Szigeti portamenti. There is nothing

understated about the playing nor does the performers’ obvious respect

and admiration tempt them toward the lax.

As I said this is one of the most decisively important

sonata recitals on record. Its survival is owed to Harold Spivacke,

Director of the Music Division of the Library of Congress, and its continued

place in the catalogue in Vanguard’s exemplary production is a matter

for rejoicing.

Jonathan Woolf