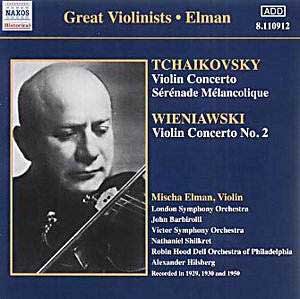

Naxos continue their invaluable series of budget price

historical issues with this release celebrating Mischa Elman (1891-1967).

Born near Kiev, Elman began to play the violin at the age of four. Seven

years later his talent was such that he was accepted as a pupil by the

great Leopold Auer in St. Petersburg (it’s Auer’s edition of the Tchaikovsky

concerto which is recorded here.) However, Elman’s formal training only

lasted until he was fourteen. After 1911 he was based in the USA. Tully

Potter, the author of the accompanying notes comments that, after early

celebrity, by the 1920s Elman’s star was eclipsed by the even brighter

star of Heifetz.

Potter credits Elman as the man who "initiated

and inspired the wave of superb Jewish violinists who poured out of

the East European ghettos in the first quarter of [the twentieth] century."

On the evidence of these recordings he certainly lacked Heifetz’s steely

virtuosity and panache. On the other hand, he possessed a warm, generous

tone and, as Potter observes, it seems that he was more effective in

slower music than in passages of "fireworks".

This performance of the Tchaikovsky concerto is one

of the most mellow, reflective even, that I can recall hearing. For

example, the passage following the first movement cadenza (track 1 from

12’22") is played with an unusual degree of seamless legato; I

can imagine many listeners will find the playing here too smooth.

The first movement as a whole is almost gentle in Elman’s hands; it

is certainly poetic but after a while I began to crave more urgency

and fire in the playing.

The wistful melancholy of the slow movement suits Elman’s

style better. Indeed, this is a rather affecting account of the music.

The finale has something of the bite that was missing in the first movement

- though it could take more. The accompaniment from Barbirolli and the

LSO, though rather backwardly recorded, seems deft and attentive. It

was work such as this which brought Barbirolli to the notice of several

great soloists and helped to lead him a few years later to the podium

of the New York Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra. Though the balance

favours the soloist at the expense of the orchestra (as was usual in

those days) the sound is perfectly acceptable and Mark Obert-Thorn’s

transfer is a good one.

The source material for the other Tchaikovsky item

was clearly less satisfactory for there is quite a bit more surface

hiss apparent. Elman’s performance of the Sérénade

Mélancolique is similar to his account of the concerto’s

slow movement. He is at home with the songful nostalgia of such a piece

and plays it with affection and feeling. It may be a fairly slight work

but Elman invests it with just the right degree of pathos, without over-indulgence.

The sound of his violin reproduces quite well but the orchestra sounds

confined. To my ears the HMV engineers, working in the Queens Hall achieved

much better results than did their American colleagues a few months

later

The Wieniawski concerto was recorded much later in

Elman’s career and, naturally, it gets better sound. The orchestra,

of course, is the Philadelphia Orchestra, playing for contractual reasons

under a none-too-subtle alias. Here they are conducted by their then-Concertmaster

and Assistant Conductor, Alexander Hilsberg, who was himself a pupil

of Auer. The recording was made in a pretty reverberant acoustic but

still sounds well. I was intrigued by the rather east European sound

of the first horn (sample his short solo on track 5 at 0’17").

At this time American orchestras very often showed the influence of

European Jewish émigrés in their string sections but it

is much less usual, I think, to find such evidence among wind and brass

players. Hilsberg and the orchestra support Elman well.

I must admit that the work itself is not one which

appeals to me very much. The music seems to be pretty feeble. However,

Elman projects the solo part strongly and with conviction. Once again,

he appears to best advantage in the slower, lyrical passages and the

second movement, a Romance, strikes me as the most successful.

This is something of a mixed disc. The interpretation

of the Tchaikovsky concerto is idiosyncratic. As such, it will not appeal

to all but it is an interesting alternative view and it is certainly

a sincere account of the work. It would not be a first choice but it

should not be overlooked. If the Wieniawski is to your taste, you will

want to investigate this performance. These are truly performances from

another age and will be of great interest to violin aficionados though

their appeal to non-specialist listeners may be more limited, even at

the Naxos price.

John Quinn