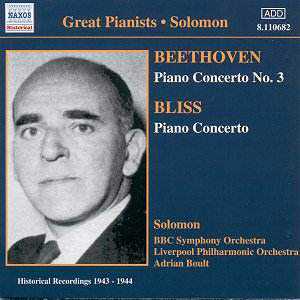

Another splendid Naxos Solomon disc, this time of the two Concerto

performances recorded during the latter stages of the War of works closely

associated with the pianist. He had first played the Beethoven C Minor

in 1912 with Henry Wood at Queen’s Hall and his later recording, from

his complete cycle, with Herbert Menges and the Philharmonia has tended

rather to obscure the qualities of this 1944 traversal which are very

considerable indeed. It begins in emphatic form with strong string fortes

from Boult alternating with woodwind diminuendos. Solomon himself enters

to coruscate with some rhythmic impetus in the left hand from 4’50 – his

balancing between the hands is magnificent – and there is evidence everywhere

of the superiority and sophistication of his rhythmic and tonal reserves,

never paraded, always turned inwards to the source of the score itself.

The war-depleted BBC Orchestra manage crisp attacks; their very distinctive

woodwinds and the oboe (I assume it’s Terence McDonagh) make strong contributions

and galvanise the movement. As was his wont Solomon plays the Clara Schumann

cadenza – probably introduced to him by his teacher Mathilde Verne, herself

a famous Clara Schumann pupil.

It’s a commonplace of course but it has to be said

nevertheless; Solomon phrases the second movement with such simplicity

and honesty that other pianists sound gauche or point scoring in his

wake. The gradients of his tone and the proportionate ascending runs

weighted with absolute naturalness are but two examples of the remarkable

artistry of the pianist. Boult himself sensitively withdraws volume

to match his soloist suffusing the movement with a grave delicacy. And

how well Boult moulds the violins’ counter theme in the Rondo finale,

how well both oboe and clarinet sing out and how vigorous and life enhancing

is Solomon’s playing.

The Bliss Concerto was written for Solomon who premiered

it at the New York World Fair in 1939, for which it had been commissioned,

where it was played at Carnegie Hall with Boult at the helm of the New

York Philharmonic. In his memoirs Bliss remembered Solomon nervously

pacing up and down backstage before that June 1939 premiere wondering

aloud whether he could go out and play at all. In 1943 with the then

leading British Orchestra, the Liverpool Philharmonic, Solomon made

a recording of the work, produced by Walter Legge, and again conducted

by Boult. The hyper-Romantic virtuosity of its syntax holds no fears

for Solomon. In the first movement’s virtuosic but stentorian opening

– which encloses a remarkably static outburst – he is fully in control

of the tricky rhythmic patina of the work. The orchestral instrumentalists

make their presence felt as well – flute, clarinet (Reginald Kell?)

and violin (presumably Henry Holst) all bring real distinction to the

movement. But always with Solomon bravura is integrated, virtuosity

subsumed to musicality; listen from 12’00 to the quicksilver changes

of mood and from 13’45 where there is absolutely no forcing or playing

through the tone even at this dramatic structural juncture towards the

movement’s close. In the second movement Solomon reveals his chamber

instincts for coalescing the faster and slower sections, for exchanges

with orchestral soloists, for exploring the sometimes complex Romanticism

at the heart of the Theme and Variations. Boult meanwhile encourages

sensitive phrasing from the strings in response. The rather Russian

finale is notable for some fascinating piano/woodwind exchanges and

for Solomon’s traversing of the demanding piano part with extraordinary

control. The final tremendous peroration, with its dramatic diminuendo

and final outburst, is a real tour-de-force, one through which Solomon

and Boult manoeuvre with real panache.

The transfers are excellent and the presentation comprehensive

and thoughtful. Very strongly recommended.

Jonathan Woolf