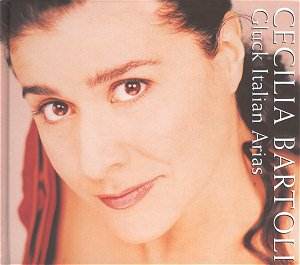

Now this has got to be great. Well, it really does

have to be, doesnít it! Cecilia Bartoli, fabulous Cecilia Bartoli, with

those deep, dark eyes riveting you from the cover (but classically draped

to match the subject, a far cry from the days when her selling-point

was her motor-bike leather and, yes, I confess it, I looked back over

my shoulder with the rest of them when I saw her poster on the billboards).

This is classical musicís hottest young female singer and thereís nothing

I or any other critic can say to convince you otherwise. The question

is, do I want to?

Now, to take a more down-to-earth line, letís start

with the programme. And weíve got to admire her for putting her clout

behind a record of Gluck, and a record of Gluck without an Orfeo

or an Alceste in sight. This is all pre-reform, Italian-period

Gluck, to texts by Metastasio, and six out of eight are claimed as first

recordings (how extraordinary, in this age of rediscoveries, that so

many Gluck operas have remained buried). As a publicity ploy, this might

pay off, and it deserves to; and if it does, Gluck will benefit as much

as Bartoli, so letís admit that it shows a real love of music to do

this.

A love shared, I would say, by all concerned. I daresay

sales would have been much the same with a scrappy booklet and no texts,

but we get a handsome hardcover book which, though small, would grace

any coffee table. In thick, glossy paper, old-style lettering and artificially

yellowing pages (but hey, this is a disc thatís meant to last, what

colour will this paper be when itís really old?), it carries

a thorough essay by Claudio Osele plus full texts in four languages,

reproductions of contemporary paintings and engravings and, slipped

delicately into the back of it, an afterthought as it were, is the little

matter of the disc itself.

Another aspect is the time and care that must have

gone into the accompaniments. The Akademie für Alte Musik Berlin

are a very high class early-instrument group. All too many early instrument

groups these days have become so proficient at their job, and so eager

to expunge memories of the time when early instruments just sounded

like bad instruments badly played, that their one desire in life seems

to be to persuade listeners that they are not really playing old instruments

at all, so whereís the point of it? The Berlin group combine a clear

relish of the piquant timbres of their instruments and the "unusual"

(to our ears) orchestral balances that emerge, with an absolute precision

of intonation and ensemble and a real rapport with the singer. And all

this, look you, with a leader not a conductor, and this surely means

real rehearsals and real musicianship from singer and players alike,

when a hard-boiled professional band under a hack conductor could have

sightread the accompaniments on the spot.

No doubt all these extras will be covered by the sales

of the record, but when we think of all the cost-cutting that could

have gone on without adverse effect on the economic return we can only

be thankful that there are still people in high places who care about

these things, and oneís eye lights on the well-respected name of Christopher

Raeburn as producer and suspects he might have had something to do with

it.

So on to the Bartoli phenomenon itself, and phenomenon

it is. She has been criticised in the past for two things in particular:

her aspirates and her vibrato. Regarding the aspirates I can give her

a clean bill of health; her brilliant passage-work is all crystal clear

without a trace of an unwanted "h" anywhere. And not long

ago I was listening to a bass "hahaha-ing" his way through

the Bach Christmas Oratorio so Iím the first to protest at an aspirate

when I hear one. I also note less of the breathy, little-girl eagerness

which used to be a mannerism. Is she growing up?

About the vibrato, I laid into her contribution to

the recent recording of Rossiniís Le nozze di Teti (DECCA

466 328-2) pretty unceremoniously. I donít know if those sessions

were particularly fraught, or whether she was having a bad day, but

here I find that, though the thing is pushed continually to the brink,

it does seem to be under deliberate control. I also find that it is

part and parcel of her artfully feminine way of keeping us guessing

(this is one aspect of the Bartoli phenomenon). Will the next phrase

come out schoolgirlishly "straight" and pure, or will she

turn on the full vibrato? If you want to hear her absolutely tearing

passion to tatters, and apparently the voice with it, go to Vitelliaís

aria "Ah, taci" from La Clemenza di Tito. But then

turn to the piece from La Semiramide riconosciuta and its plentiful

trills allow us to study what she means by a trill and what she means

by vibrato. If the rapid oscillation is between two recognisable notes,

that is to say a semitone or a tone apart, then itís a trill. If itís

between something much smaller then itís vibrato. But the technique

is the same. Itís not the same thing as the natural vibrations of a

voice which is not making a deliberate vibrato but simply resonating

freely. And it is emphatically not the tremor, all too easily disguised

as vibrato but ending up as sheer squalliness, of a voice which lacks

proper breath-support. If Bartoli lacked that essential, she just couldnít

hold the long, high lines as she does in many of the slow arias. So

the vibrato is a deliberate part of her vocal production and we have

to take it as part of the phenomenon.

Another of her mysteries is, is she really a soprano

or a mezzo? Logic would say that, when she can hold a high, pure line

going up to an effortless top B, as she does in Sestoís aria from Clemenza,

when her coloratura sometimes goes higher and when the general tessitura

of the pieces is that of a soprano, albeit one able to descend below

middle C from time to time, then she must be a soprano. But then her

middle register assumes a contralto-like richness which enables her

to move downwards without recourse to chest tones (any soprano can do

a Marlene Dietrich imitation if she wants to). On the other hand, she

can also take her chest voice up remarkably high. And these are all

things which denote a mezzo-soprano. So she remains individual, elusive

and, above all fascinating.

She is also a singer of our time. It is said that those

who hear her live find her voice disappointingly small. I canít speak

of this from experience but even if it were so, I donít know if this

necessarily disqualifies her as a great singer in a loudspeaker dominated

age; the important thing is that the results coming out of the loudspeaker

are those intended and that they reach the public they are aimed at.

And ever since the gramophone was invented there have been singers (famously

Peter Dawson) who were essentially gramophone singers and others (in

the post-war years, Leyla Gencer and Raina Kabaivanska) whose voices

recorded badly and were in fact recorded very little. The recitative

to the Ezio piece seems to me pure "microphone singing"

and would hardly come across the footlights live (I presume she gives

it more sound in public?). But when the object is to make a recording,

and when it succeeds on these terms, does this matter?

It occurs to me that I havenít said anything about

Gluck himself. The notes begin by quoting him as stating, in the preface

to the first real "reform" opera, Alceste, "I

have made every effort to restore music to its true role of serving

the poetry by means of its powers of expression". Cynics always

did say that this stemmed from a recognition that his music was not

of itself sufficiently strong in personality to hold the stage except

in tandem with the librettist. Here, some years before his "reform",

his music forms a perfect vehicle for the singer to go through the whole

gamut of the charactersí emotions. It is all totally effective (I thought

only that the Semiramide aria was banal; the notes attribute

an ironic sense to this. Unfortunately, irony in music tends not to

outlive the age it was written for). At the end I found I remembered

the moods, which are clearly delineated and well-varied, and the general

experience, rather than any particular phrase, but this is not incoherent

with Gluckís intentions. Maybe the music will lodge itself in my memory

on rehearing it (I shall certainly do so). Even so, my appetite is whetted

to hear these unrecorded operas complete.

I think no one will remain indifferent to this disc.

It is an absolutely involving experience by one of the phenomena of

our times.

Christopher Howell