|

|

Search MusicWeb Here |

|

|

||

|

Founder:

Len Mullenger (1942-2025) Editor

in Chief:John Quinn

|

|

|

Search MusicWeb Here |

|

|

||

|

Founder:

Len Mullenger (1942-2025) Editor

in Chief:John Quinn

|

BARGAIN OF THE MONTH

|

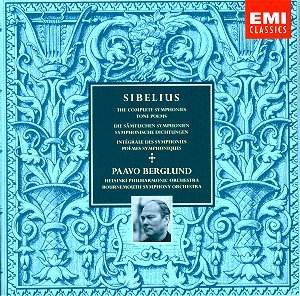

Jean SIBELIUS (1865-1957) BUY NOW |

|

Disc 1 [78.20]

|

|

The late 1960s and early 1970s were stirring times for Sibelius lovers in the British provinces. While the authority of Sir Thomas Beecham was receding into historical memory in London, the passionate insights of Sir John Barbirolli were still to be heard in Manchester, Gibsonís sinewy, often electric interpretations were gaining a reputation far beyond Scotland, Groves was no mean interpreter in Liverpool and, in 1970, the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra and Paavo Berglund hit the headlines by bringing to London the first performance in the 20th Century of Sibeliusís early choral symphony "Kullervo", suppressed by the composer after a few highly successful performances in 1892 and at last released for public hearing by his heirs.It was a shrewd publicity move in many ways, first and foremost for the orchestra. Having long been viewed as a passable provincial band, decent enough for a town where elderly couples could be seen pushing their elderly dogs in perambulators along the sea front (I've seen photographic evidence!), in 1961 it had succeeded in capturing as its principal conductor Constantin Silvestri, an internationally renowned maestro who had recorded for EMI with the Berlin and Vienna Philharmonics as well as a long series with the Philharmonia. Silvestri had quickly shown the truth of Karajanís dictum that there are no bad orchestras, only bad conductors, and before long the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra was one of the finest in the land. London began to take note and the EMI recording teams returned to Bournemouth (or rather, Southampton, for acoustical reasons) after a long absence. But then, in 1969, Silvestri died at the premature age of 55 and tongues began to wag. Was the great work going to be undone?Though Berglund took up his appointment as principal conductor in 1972 (he remained till 1979), following the "Kullervo" performances and subsequent recording he was the undisputed conductor-in-waiting. It was also clear from that moment that, while he favoured a rigorously logical, structural approach to music expressed in a well-balanced but sober, granite-like orchestral sound, at the opposite pole to Silvestriís often highly personalised, rhapsodic and colouristic interpretations, in terms of discipline, articulation, tuning and general blend there was to be no relaxing of standards.As part of a busy recording schedule the complete cycle of Sibelius Symphonies followed, together with a wide number of miscellaneous pieces, some of which had not been recorded before. As this was before the days of "complete cycles" of every scrap the composer wrote, the non-symphonic works create a rather piecemeal effect these days. The chief absentee among the tone poems is "Nightride and Sunrise", and the "Lemminkainen Legends" are limited to the most popular two, perhaps because Groves had recorded the set in Liverpool during this same period. Sadly, the missing two are those which would have particularly benefited from Berglundís structural control and it is to be hoped he will record the complete opus one day. The lack of the middle movement of the "Karelia" Suite is odd rather than particularly serious.In 1984, EMI profited from a visit to London by the Helsinki Philharmonic to record Berglund again in Symphonies 4 and 7 in digital sound, with sufficient success to send a team to Helsinki to complete the second Berglund cycle, including a new "Kullervo". Berglund has subsequently researched into the texts of the Sibelius Symphonies, correcting a number of errors in the printed scores, and is recording his third cycle with the Chamber Orchestra of Europe.And all this began in a period when the rage for Mahler, in so many ways Sibelius's symphonic antithesis, was at its height and many were asking what future these "conservative", "anti-modernistic" works really had, if any, when their high reputation had in any case been mainly an Anglo-Saxon phenomenon. (To this day, well-read Italian musicians will assure you that Sibelius was a minor exponent of the 19th Century nationalist school who wrote a piece called "Finlandia"; the situation is not far different in France and even Germany, in spite of Herbert von Karajan's advocacy, has never entirely accepted the idea that a Scandinavian composer could have written proper symphonies). Few would have guessed that by the end of the 20th Century Sibelius would have been a declared influence on many far-from-conservative composers, such as Peter Maxwell Davies and George Benjamin, or that in an age where man is having to re-invent his relationship to nature at the cost of his own survival, Scandinavian architecture and its musical parallels in the work of Sibelius might stand as shining beacons of modernity, first lit nearly a century before. Or that the interpretations of Berglund might come to seem in many ways those most closely in tune with Sibeliusís new-found role as a contemporary composer.With implacably democratic logic (Bournemouth 4: Helsinki 4) EMI have given us the Helsinki cycle of Symphonies plus the two choral pieces which acted as fillers for the original LP issue of the Helsinki "Kullervo", but have gone back to the Bournemouth "Kullervo" and collected together the Bournemouth recordings of the miscellaneous pieces. Any logic behind the actual ordering of these pieces escapes me, especially in discs 6 and 7 where the higgledy-piggledy chronological order does not aid appreciation of the lesser, earlier pieces (disc 8 actually makes quite a nice programme of mainly theatre music).Although the recordings were made over a period of 17 years, the set impresses by its total consistency. The Bournemouth recordings possibly offer a wider stereo definition deriving from a closer sound, and just occasionally threaten very slight distortion at climaxes. The digital Helsinki recordings have more depth and compactness if a little less immediacy and are best heard with the volume as high as you dare. I made a few spot checks with the LPs (I had to hand the Helsinki choral pieces and most of the Bournemouth shorter pieces) and found such slight differences as to wonder if I were not imagining them. Unless you want demonstration state-of-the-art sound you'll find it all entirely satisfying.Equally consistent is the orchestral playing, the general standards of precision and, most notably, the timbres, the colours and the style of articulation. So consistent was Berglund in his demands on the two orchestras over the years that one can pass back and forth without finding any discernible difference between them. Consistent, too, is the unhurried, yet never dragging, style of interpretation which seems to find the tempi from within the music and to allow events to unfold with absolute inevitability, never pushing onwards, never holding back. Set down on paper this may sound a little safe and dull, but be assured that it does not preclude excitement (some scarifying climaxes in "Tapiola") or warmth (the 6th Symphony's opening movement is sung out strongly). It is on account of this unfailing contact with the music's natural, organic growth that I make my claim that Berglund's interpretations are those most in tune with the role Sibelius is coming to play in the 21st Century. I am speaking principally of the Symphonies, it will be evident, but I should point out that the conductor shapes the lighter, slighter pieces with a sense of their delicacy and with a sure sense of the rubato and rhythmic pacing needed to bring them to life.There have always been those who feel that Berglund is too slow, for example in the first movement of no. 2 or in the more heroic no. 5. I felt that the sense of rhythmic pulsation he creates at the opening of no. 2 more than justifies his tempo, as do the steep accelerandos he is able to make when called for. It is true that in certain moods I might prefer to hear these two symphonies propelled with a greater electric charge, but conductors who content me in this have a nasty way of bulldozing through pieces like the fragile central movement of no. 3 or the whole of no. 6. After a few experiments I gave up comparisons with other performances since I feel that, while taken singly it might be possible to find particular favourites for each symphony (the choice is very rich, after all), a more consistently satisfying cycle could hardly be achieved. Also, by not over-playing no. 5 and conversely by presenting no. 6 with unusual power, Berglund sees that the cycle moves inexorably towards its culmination in no. 7.I didnt have the Bournemouth symphony cycle for comparison (nor the new COE versions) but I was able to compare the present "Kullervo" with the Helsinki one. In four movements out of five the differences are minimal some conductors vary their interpretations more from one evening to the next than Berglund has in fifteen years. The fourth movement, however, finds him taking a notably steadier tempo in Helsinki. In theory this is in line with his pursuit of a natural, unhurried delivery, but since this is early Sibelius and a somewhat thin, overlong movement, I must say I prefer the more exciting Bournemouth version. Both versions use the Helsinki University Male Choir, but the Helsinki one adds to it the State Academic Male Choir of the Estonian SSR. This is a magnificent body and provides the one point where the Helsinki version is definitely preferable. With the soloists it goes the other way. Raili Kostiaís rich tones and secure delivery can be enjoyed for their own sake, whereas Eeva-Liisa Naumanen is more effortful and bumpy. Odd that she is named as a mezzo-soprano and Kostia as a soprano; my ears tell me it is the other way round. What is even more surprising is that Jorma Hynninen, on the Helsinki disc, despite his high reputation, sings with a bleating vibrato under stress so here, too, Bournemouthís soloist is preferable. All of which seems to point to the present performance having been the right choice.If you need to get your basic Sibelius then you can safely start here. (You will have to get the Violin Concerto separately; other omissions can be dealt with later). If, like me, you have built up your Sibelius a bit at a time from various sources, you might find it a revelation to hear one of the greatest symphonic cycles under a conductor who shows such a deep understanding and profound identification with it. In the end I felt I was listening, not to Berglund, but to Sibelius.One last point. Berglund's particular gifts in expounding symphonic structures would surely make him an ideal conductor of Bruckner. Yet to the best of my knowledge he has recorded none at all. So how about it?Christopher Howell |

|

Return to Index |