The trouble is that for years and years Rubbra was

notoriously the prime target of those "progressives" who sought

to dictate public taste with their simplistic formula "atonal is

good, serial is better, a dose of healthy fragmentation is better still".

With all the force that William Glock, the BBC and their fellow moral

(?)-crusaders brought to bear on the systematic elimination of tonal

old-fogies like Rubbra from our musical life (all right, don’t write

in about the black list that wasn’t, I know it didn’t exist in a pen-to-paper

sense, it didn’t need to), it was only natural that the legend got about

that there was a stack of sheer masterpieces, every one of them more

spiritually enriching than the next. So fiercely was this view held,

with a conviction normally reserved for those scientific laws which

make the world go round, that still today, when tonal music can be heard

and even written once more, no one wants to risk his neck by admitting

that Rubbra’s detractors had at least a point; namely that when not

at his best he could, in his very different way, be just as thick-textured

and obtuse as any Schönberg disciple.

What doesn’t work in Rubbra can be seen once for all

in the first of his 8 Preludes for Piano, op. 131 (which he once played

himself for a BBC broadcast – does the tape still exist?). The opening

is spacious and attractive and promises great things. Then with inexorable

logic the contrapuntal lines wind upwards (the piece covers a mere page)

until they climax on a fierce dissonance, and Rubbra’s insistence on

one sort of logic seems to have led him to reject another which might

have revealed to him that he had by this time landed in a zone high

up on the piano keyboard where his climax chord sounds perfectly horrible

and does not make a satisfying climax at all.

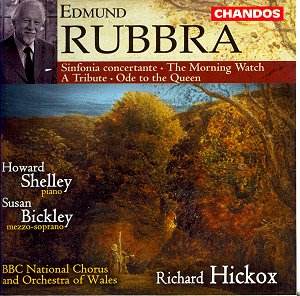

And so it is with "The Morning Watch", where

the grave orchestral opening pre-announces much spacious and noble development

to come. But then, as the counterpoint piles up and the choir is crowded

into action, everybody sounds to be bawling his own contrapuntal line

at the others, the recording seems on the point of overloading under

the weight of it all and the best the conductor can do to elucidate

it is to balance it as a sort of two-part invention for trumpet and

high strings, with all the rest left as an indeterminate mess. "Oh,

but the transcendental mysticism of it!" his admirers will say,

but the mystery to me is where the blame for the confusion lies. Is

the Brangwyn Hall too small to contain all the sound? Did the engineers

mix in too much ambience at the expense of clarity? Did Hickox not do

enough to sort out the balance problems? Did Rubbra himself pile it

on too thick? I suspect it’s a bit of all four, but regarding the latter,

remember how Stokowski gave the Fifth Symphony a few performances and

was accused of gilding the lily, so clear and transparent were the textures

(now, does a tape of that survive anywhere?), until the composer

said that finally he had heard the symphony as he had written it. Small

thanks to the Boults and Barbirollis who had done their best by him

over the years (and incidentally, the c.1950 Barbirolli Fifth is a model

of textural clarity compared with the present offering).

Rubbra did clarify his orchestral textures with the

years and the opening of "Ode to the Queen" impresses by its

fine luminosity and transparency, as well as its vitality. The problem

is that vocal writing may not have been Rubbra’s strongest suit. In

"The Morning Watch" he pushed the voices up dangerously high,

and in this piece Susan Bickley copes – with impressive security and

clear diction, I should add – with a line which often seems more for

pure soprano than mezzo. It’s all in that semi-melodic declamatory style

which composers of the Britten generation could churn out by the furlong

(now come off it, Chris, you’re a paid-up British Music Society member,

they’ll be after your blood for this!) and which, when it wants to emphasise

a word – and it emphasises a good many – has the voice shoot up to a

sudden high note; see "perfect emblems" in no.1, "gladsome

welcome" in no. 3. Half the time, is there really any reason

why the voice should go up rather than down, down rather than up? I

did appreciate the imaginative atmosphere of no. 2 and the general lilt

of the last, though the end sounded unmotivated to me (Adrian Yardley,

in his notes, describes it more kindly as "surprising").

"A Tribute" has an opus number consecutive

to "The Morning Watch" and goes through the same motions on

a smaller scale – the notes are different but the music

is the same so did he really need to write it? Unkind phrases began

to turn in my head – "says in four-and-a-half minutes everything

he spent his life trying to say" was going to be the line – but

then came the "Sinfonia Concertante" (first on the disc, but

I heard it last). Yes, you get the usual slow, grave beginning, but

right from the start, with the piano’s rippling entry, somehow you know

the composer is fully engaged. When the Allegro comes there is an angry

power to it that is quite riveting and the movement succeeds in alternating

the two tempi with total mastery and conviction. The brief "Saltarella"

second movement is no mere folkloristic romp, it has a granitic strength,

and finest of all is the slow "Prelude and Fugue" finale,

written in memory of Rubbra’s teacher and friend Gustav Holst. On the

face of it, the prospect of a fugue by Rubbra is about as attractive

as that of one by Max Reger (but also in that case, expectations can

be belied by the results). But listen to how the moving Prelude halts

on a chord of C major and the Fugue theme rises from it on the cor anglais

– an unforgettable moment indeed, yet it is capped by the entry of the

piano which, after a lengthy orchestral working of the theme, comes

in as if it had nothing to do with it, and yet you are immediately convinced

that it had to enter this way.

A concertante work with a slow, quiet ending is unlikely

ever to become popular, yet this surely ranks high among 20th

Century works for piano and orchestra, of whatever nationality. Shelley

and Hickox plainly believe in it and their performance is totally convincing.

So the disc is an essential purchase, no matter what I’ve said about

the other works.

Let’s be clear, then: Rubbra was shamefully

treated, he did write a number of masterpieces, but he didn’t

only write masterpieces (what composer did?) and, now that we

can actually hear a certain quantity of his music, we have to decide

which are the works we really want to keep with us. If you don’t

know the symphonies yet, start there, but the "Sinfonia Concertante"

is another must.

Christopher Howell