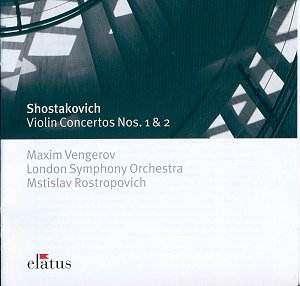

These performances were widely admired in their original

issues, on separate CDs with other repertoire, but it seems most sensible

to have the two Shostakovich violin concertos coupled together on a

single CD. Vengerov performs both of them with consummate artistry,

and well did he deserve the accolade of ‘Record of the Year’ which he

gained for the First Concerto on its original release in 1995.

This work is unusual in having two designated opus

numbers, the composer having withdrawn the work around the time of the

1948 Congress of Soviet Composers. At this notorious event the major

figures of Soviet music - Prokofiev, Khachaturian, Miaskovsky, Shostakovich

- were roundly denounced by Stalin's henchman Zhdanov, since the Party

viewed their compositions as examples of 'individualism' and 'bourgeois

decadence'.

It was a full seven years later, two years after Stalin's

death, that the premiere of the concerto took place. The soloist, and

the work's dedicatee, was the legendary David Oistrakh, who had advised

Shostakovich on technical matters relating to the violin part. But while

the music certainly makes many demands on the player's technique, the

expressive qualities of the material always take priority.

Vengerov's performance is likely to be the greatest

since Oistrakh, although in fairness Hilary Hahn has been identified

strongly with the piece quite recently. The music has a wide expressive

and technical range, much of it uncompromisingly slow and introspective.

If anything, this aspect is more demanding for the player than the more

obviously virtuoso fast section. And it is here that the warm and secure

tone of Vengerov really pays dividends. His performance is thoughtful

and deeply felt. Therefore the arrival of the finale is an entirely

logical result of all that has gone before, and for the listener the

experience grows with each hearing. For this is a magnificent work,

revealing the composer at the height of his powers.

The Violin Concerto no. 2 is probably the least familiar

of all the Shostakovich concertos, though it is certainly as fine a

composition as its companions. It was written in 1967, twenty years

after the Concerto no. 1, and was intended as a sixtieth birthday present

for Oistrakh. The composer miscalculated, however, for the dedicatee

was still a mere fifty-nine when he gave the first performance in October

that year.

In its general outlook the score is typical of Shostakovich's

later music, the spare textures reflecting the intensity of feeling

which obsessed him after he had suffered a severe heart attack in 1966.

The meditation with which the Concerto begins sets the tone, just as

the equivalent movement in the Concerto No. 1. Shostakovich described

this theme as the 'betrayal motif', which was possibly a reference to

the harsh Brezhnev regime and its treatment of dissidents who were in

many cases his friends. But soon the despair of this lyrical meditation

transforms the motif into a frenetic, even grotesque, rhythmic activity;

and these somewhat disconcerting shifts of mood, which form a fundamental

aspect of the composer's style, recur throughout the composition. The

sinister pantomime is emphasised by the extremities of the scoring:

at one point the soloist shares a competitive duo with beating tom-toms.

This music is highly charged and a worthy successor

to its illustrious predecessor. Again Vengerov's technique is flawless,

but more important, his understanding of the music is palpable. The

expressive range is effortlessly but meaningfully conveyed, with tempi

expertly thought through, for which all praise to the composer's friend

Mstislav Rostropovich. The LSO are on top form throughout, but inevitably

it is the playing and interpretations of Maxim Vengerov that steal the

show.

Terry Barfoot