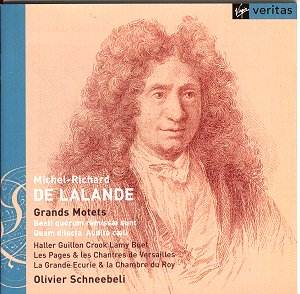

In 1683, King Louis XIV instituted a remarkable competition

to find suitable composers for his new chapel at Versailles. A national

competition, advertised in the Mercure Galant, it attracted 35

entrants. For the second round, the 16 selected candidates had to compose

a grand motet to the text of Psalm 31(32), 'Beati quorum remissae

sunt'. The composers were all isolated in separate rooms to ensure that

there was no cheating. The motets were all then performed before the court

and their relative merits decided upon. One of the composers selected

was the young Michel-Richard de Lalande and the first item on this disk

is his entry in the competition. Remarkably, this is the only motet from

the group to survive. In this, its first recording, it is accompanied

by two other of his early grands motets.

The grand motet was a genre that was developed

to suit both Versailles and the King's image, solemn and majestic. Disliking

high mass, the King habitually attended low mass and the grand motet

provided suitable musical accompaniment whilst the priest said mass.

Musically the form took something from the style that Lully had developed

for the opera. Lully’s Te Deum, performed in 1677 using a full orchestra

of violins, flutes, oboes, bassoons, trumpets and drums, was an early

precursor of the new genre. Lalande wrote over seventy grands motets

and it is a measure of his success in fashioning a new style, that to

our ears these motets sound so redolent of Versailles and the court

of Louis XIV.

This is toe-tapping music. Lalande's use of dance rhythms

and the secure, stylish performances from the soloists, Les Pages et

les Chantres de Versailles, and La Grande Ecurie et la Chambre du Roy

under Olivier Schneebeli, mean we can well understand why this music

was popular with Louis XIV. They make a very well upholstered sound,

with a choir of thirty-one and orchestra of twenty-one.

In constructing the motets, Lalande eschews the model

of the German cantata with its large-scale movements. In all the motets

on the disk, each movement consists of a sequence of choruses, solos,

ensembles and ritornelli. The text is set almost in dialogue form, Lalande

using alternating soli, chorus and ensembles to dramatise the words,

often creating quasi operatic structures. There are no opening choruses,

all the motets open with solos or duets and the chorus come in when

Lalande feels the need for them to question or comment on the soloists.

From the first notes of its French overture, the first

motet 'Beati quorum remissae sunt' transports us into a world where

the operatic works of Lully are not far away. As befits is origins,

this setting of Psalm 31 ('Blessed is he whose transgression is forgiven')

is on a very grand scale. The second motet 'Quam delicta', is a rather

more gentler piece reflecting its setting of Psalm 83 ('How lovely are

thy tabernacles, O Lord of hosts'), starting with an opening movement

of a gentle duet over a dance-like accompaniment for with two flutes,

and throughout the remainder of the piece, joyful dance-like rhythms

are never very far away. The final motet, 'Audite Caeli', sets words

from Deuteronomy, is an altogether graver affair. Full of imaginative

touches, LaLande uses silence and hesitation in the opening movement

to depict Moses’ terrible warning ('Give ear, O ye heavens, and I will

speak').

All five soloists perform with enviable security and

naturalness, perfectly at home in this distinctive musical world. To

single any one soloist out for notice is invidious but Howard Crook's

mellifluous haute-contre deserves special mention, such high tenor parts

are not easy, particularly when performed as naturally as here. The

orchestra is given many opportunities to shine, the motets are full

of orchestral ritornelli and interludes. La Grande Ecurie et la Chambre

du Roy play with impeccable style and it is a shame that more studio

time could not be found to cure one or two slight untidinesses.

Faced with such excellent performances, it seems churlish

to make complaints. But all three motets are performed with a rather

intense high energy, perhaps an eagerness to make the point. I began

to wish for a more under-stated performance sung with a relaxed confidence

and naturalness. You only have to listen to Ex Cathedra under Jeremy

Skidmore on their recent Hyperion disc of Lalande grands motets.

Admittedly they are performing motets dating from later in his Lalande's

career, but they seem to perform them with an enviably relaxed naturalness.

The booklet contains an excellent, extensive and informative

essay by Jean Duron and the words in three languages, so it seems strange

that nowhere is there a breakdown of which movement is sung by whom.

But these are small complaints. This is a highly recommendable recording,

casting light on Lalande's early career and providing a memorable souvenir

of a fascinating competition. I would not recommend it as a starting

point to explore Lalande's grands motets, but if you are familiar

with his greater works, then do try this admirable collection of his

early pieces.

Robert Hugill