Listening to the second of the six Brandenburg Concertos

in these reissued performances by Tafelmusic gives the overall flavour

of this interesting set. The two outer movements are taken at tempi

that are rapid in the modern way Ė consistently one or two metronome

points above Benjamin Brittenís interesting versions from 1968 Ė but

always comfortable and logical, with no extreme positions taken and

the playing never seeming rushed. Phrasing in slow movements is natural

and affectionate, where tempi again are carefully chosen to allow the

music to move on but without hurrying. The playing of the four soloists

is first-class, technically secure without drawing attention to itself,

and the recording is excellent. One could end there and recommend this

set as an excellent opportunity to acquire all six Brandenburgs at a

knockdown price, and this is, indeed, my view. Yet there are two aspects

to these performances which trouble this listener, at least. First of

all, and compared to other readings, the playing is sometimes a little

lacking in charm. I think this is mainly a matter of accentuation which

can seem relentless, even heavy at times; and whilst Iím not advocating

full bow strokes in the romantic manner, I do find the playing too staccato

too much of the time, and with too little variety within the staccato

which results in playing which lacks affection. I also find a certain

rigidity of pulse, especially in the faster movements, though this is

all part of an overall view of the music to which Iím not totally attuned.

The other problem is that although we might admire playing which doesnít

seek to draw attention to itself, preferring to let the music speak

directly to the listener, there does seem to be a lack of personality

in the playing here, giving a sort of greyness for all its technical

accomplishment. I should state that neither of these worries troubled

an acquaintance who listened, as it were, blind. Nor was I so bothered

by them when I abandoned the idea of listening straight through the

discs in favour of one concerto at a time. All the same, even if Brittenís

view of these pieces is not the one we would feel happy with nowadays,

there is never any doubt that a strong musical personality is at work

there, which is also the case with Trevor Pinnock (DG) and Jordi Savall

(Astrée). If you like your Bach robust and businesslike these

performances by Tafelmusik should certainly suit you, and they are certainly

very cheap, but I think you can find more character elsewhere.

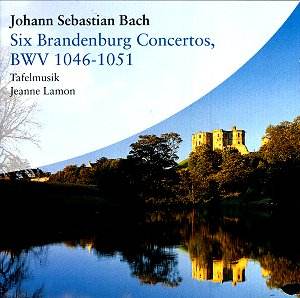

The front and back covers of the booklet accompanying

this issue carry a lovely photograph of a castle with an island in the

middle of a lake. Itís well-nigh impossible to be sure of any link between

this and the programme, but more important, when you open the booklet,

although you find the usual track listing and an interesting article

(in English only) by Julian Haylock, there is no information at all

about the performers nor about the circumstances of the recording. This

is a pity, since despite the slight reservations I mention above the

performances are excellent, and in the very extensive company of all

the different period music groups, Tafelmusik are not the best known

so it would have been welcome to have some information about them. More

serious still is the lack of any information about the soloists. They

are outstanding, and it seems to me criminal not to identify them. The

excellent violin soloist is presumably the director herself, Jeanne

Lamon, but the harpsichord playing is first rate throughout, and particularly

in the long solo in the Fifth Concertoís first movement. And the stratospheric

trumpet playing in the Second Concerto is as brilliant as it is self-effacing.

We ought to know who these players are.

William Hedley

We have information

that the harpsichordist was Charlotte Nediger