The extraordinary thing about Elman is that he seems

to have emerged fully formed as a violinist. It’s difficult now to appreciate

quite how revolutionary his playing must have sounded when, at the age

of 12 and trained by Alexander Fidelman, he auditioned for Fidelman’s

own teacher, Leopold Auer. The great pedagogue had never heard anything

like it, as he freely admitted, and Elman remains one of those rare

cases of the development of an independent tonal aesthetic in isolation

of other influences – he had never heard either Ysaye or Kreisler. His

period of ascendancy was real but brief – chronology has tended to telescope

his primacy in the concert halls of Europe and America – but it was

an unarguable one, lasting from his debut in Berlin in 1904 until the

arrival of Heifetz in 1917.

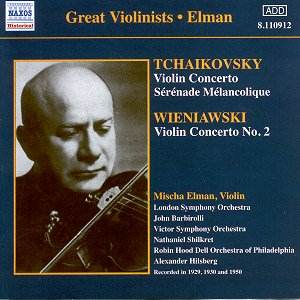

Elman’s 1929 recording of the Tchaikovsky Concerto

wasn’t in fact the first – Huberman had beaten him to it and another

Auer pupil Eddie Brown had beaten both of them, though his 1924 recording

wasn’t issued at the time and has only ever emerged on a very rare LP.

Throughout Elman’s performance we can hear the battery of devices open

to a player of his standing – succulent portamenti, a ravishing tone,

lava-like in its molten flow, which no-one, not even Toscha Seidel,

could ever match. It remains one of the most remarkable sounds in recorded

music. We can also hear the unhurried tempi, the unobtrusive excellence

of Barbirolli’s conducting, and a performance of persuasive cohesion

strictly on its own terms. As he grew older his playing slowed inordinately,

as much a question of accommodating a failing left hand as of structural

choice, though he was, by nature, generally a master of sedate tempos.

His unusual posture must have complicated the matter – he was a small,

bull-necked and stocky man with short arms and thick fingers (one of

the many reasons advanced over the years for the existence of that molten

vibrato ascribed it to the depth of his finger tip pads). Those who

have seen the Vitaphone short of 1926 contained in The Art of Violin

will have seen how he played at a definite angle, with the scroll of

the fiddle pointing downwards, the better, one supposes, to allow Elman’s

left hand to overcome stretching problems.

Ageing and a slowly diminishing technique had begun

to take their toll by the time he came to record the Wieniawski, the

other major work on this excellently transferred disc. There’s now less

of the fervid intensity in his tone but still much of the old Elman’s

tonal lustre remains. In comparison with the pin point Heifetz recording

or with the almost contemporaneous 1953 Stern one can quite see how

old-fashioned Elman must have seemed. By the side of Stern’s coruscatingly

involving playing – surely one of his greatest performances on disc

– Elman’s fires burn less dazzlingly and generate less obvious heat.

Nevertheless it’s always timely to salute Elman – the BBC has preserved

at least two recitals, from 1961, and failings acknowledged, his was

still an immense talent; let’s hope they will make an appearance in

their series. Meanwhile if you’ve never heard Elman’s 1929 Tchaikovsky

you really should. Here it is, cheap, well presented and transferred

and a fitting living testimony to a remarkable violinist.

Jonathan Woolf

Elman’s succulent portamenti, ravishing tone, lava-like in its molten

flow, which no-one could ever match. One of the most remarkable sounds

in recorded music. … see Full Review