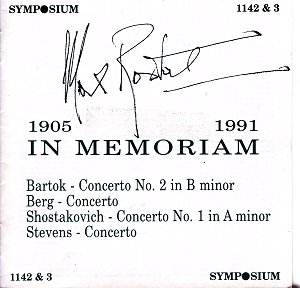

Symposium brought out a CD set devoted to the art of

Carl Flesch that contained some fabulous rarities Ė live recordings

from the 1930s, otherwise unrecorded, which opened up previously unexplorable

vistas into the breadth of his playing. And now these CDs dedicated

to one of Fleschís most outstanding pupils, Max Rostal, has in its turn

acquainted us with much that might otherwise have been lost. In his

own turn Rostal carried on Fleschís teachings and his responsibilities

as a soloist were balanced with those towards his pupils and the nurturing

of European string teaching generally. He became known prominently as

a teacher in London and later in Switzerland but in fact he had begun

much earlier, becoming the youngest professor at the Berlin Hochschüle

whilst still in his twenties. As a professor at the Guildhall School

he was as influential as his colleagues at the RCM, Albert Sammons and

Isolde Menges, and also that much neglected figure Rowsby Woof. For

all his many qualities Rostal never quite achieved the international

career that might have been expected of him. His early playing is surprisingly

engaged and fiery but as time went on it was refined into a more analytical

and tonally focused style. The earliest recording preserved here (the

Bernard Stevens) therefore finds him in his early forties, living in

London, and pursuing a career as soloist, sonata player Ė with Franz

Osborn and later Colin Horsley - and as one of the most significant

teachers in Britain.

Yfrah Neaman claims in his share of the sleeve notes

Ė in addition to which there are contributions from Radovan Lorkovic

and Rostal himself Ė that the Bartók was introduced to

Britain by Rostal but I always thought that Menuhin took that honour

in 1944. Irrespective of first performance privileges Rostalís contribution

to contemporary music was profound, tenacious, eloquent and unremitting;

he advanced the causes of composers whom he believed to be part of the

evolving fabric of violin composition whilst baulking at the emerging

avant-garde. The performance of the Bartók No 2 dates from 1962,

the most recent of the preserved concertos. There is some obvious muddiness

in the sound but there is little to distract the ear from Rostalís ardently

expressive playing. His tone is not of striking opulence but it is distinctly

personalized with an absolute core to its sound and is well attuned

to a work of this kind. His characterization of the violinís volatile

line emerges with trenchant understanding and fuses well with the vivid

orchestration Ė the orchestral glissandi, the disruptive and passionate

rhetoric. If the first movement cadenza can sometimes seem unduly discursive

it is delineated here with Rostalís characteristic intellectual rigour

though without any sense of academic or dry playing. His sovereignty

over a large architectural span can only be acknowledged with admiration.

In the second movement his "flattened" tone emphasises Bartókís

quixotic writing and he is especially astute in his preparation for

the subsequent orchestral outburst at 5.10 Ė listen also to his high

lying playing after 10.05 with orchestral harps and shimmering strings

to accompany him. The last movement with its motoric impulse is in fact

a set of reflections and refractions of the first and as Rostal points

out in his notes is of exceptional complexity and not immediately recognisable

as such; tremendously played.

The Berg dates from 1953 and is conducted by

Herman Scherchen who had given the premiere, with Louis Krasner, on

barely an hourís rehearsal after Berg had backed out. Again there are

the inevitable sonic limitations but the historical value of the performance

far outweighs the minor inconveniences inherent in the reproduction

Ė muddied balancing and some acetate thumping. Radovan Lorkovic speculates

in his notes that Rostal may have been influenced by the BBC Orchestra

and by Scherchen (the BBC had been the second to play the Concerto,

with Krasner and conducted by Webern, a performance miraculously preserved

by the soloist himself and for some years now available on Testament).

But that was a number of years in the past and he is far more likely

to have discussed tempo modifications with Scherchen which he felt engaged

with the concertoís centrality of meaning. He is tonally of great clarity

and precision, tempi slightly at variance from the norm, with at times

an unexpected lightness far removed from more unremittingly solemn performances

and as a result the concerto emerges as more entirely whole. Rostalís

vibrato usage is sparing and precisely graded. Itís not perhaps the

most emotionally convulsive performance but it is one that allows an

unimpeded view of a towering masterpiece.

Rostal believed in Bernard Stevensí work as

he did in Benjamin Frankel whose solo sonata heíd recorded for Decca

shortly before making this broadcast performance of the Stevens Concerto.

I hope that Rostalís reading of Frankelís Violin Concerto, which has

been preserved, will be made available. It was Rostal in fact who had

suggested that Stevens write a Concerto and it was completed in February

1943. Violinist and composer met frequently to discuss the composition

and Stevens willingly accepted Rostalís many suggestions and it seems

to have been a genuinely creative collaboration. Rostal edited both

Concerto and Stevensí earlier Violin Sonata for publication in 1948.

This is the earliest performance in this set and is veiled in scratch

but the solo violin emerges very forwardly balanced, emerging brightly

and unduly spotlit, with the orchestra submerged in the aural perspective.

Rostalís stentorian opening fusillade with brass interjection at 4í50

with horns emerging and a succeeding keening violin line is exceptionally

well done. He also lays strong emphasis on the troubled and powerfully

straining contours of the music, most explicitly perhaps in the cadenza

at 8.50, which one can feel Rostal relating specifically to the sense

of fracture and strain embedded in the syntax of the whole concerto.

His understanding of the adagio is matched by concomitant technical

address and this is playing of real involvement. If there is acetate

groove damage from 1.45 in the finale and the orchestra is distinctly

unhelpfully recessed here, to the detriment of the architecture, at

least one can concentrate on the solo violinís traversal of the contrapuntal

movement and the fractious rhythmic material whose occasional lyricisms

are never quite enough. We can also admire the close of the work and

the beautifully benign final bars which whilst not untroubled are reflective

and interior and movingly realised by Rostal and Groves. Lest Iím giving

the impression that this is an unremittingly grey and bleak work the

Bloch influences are certainly present and the more one hears it the

more it gains in stature.

Expectant applause greets Rostal and Sargent for Shostakovich

No 1 from 1956. Sound is rather thin and papery and this does cause

some problems not least in orchestral elucidation Ė the fist movement

orchestral counter themes go for nothing here unfortunately. Nevertheless

we can hear Rostalís expressive finger intensifications and the gradations

of his vibrato and its tactical deployment in the fabric of the score.

He is taxed but overcomes the rigours of the scherzo Ė his sense of

architectural line as ever most impressive and his tone becomes somewhat

astringent and wiry at times. There were moments in the great Passacaglia

that I found some somewhat tremulous playing, as if over vibrated in

response to perceived expectation, and not emergent from direct emotional

engagement with the music. There is also some fervently febrile playing

in this movement but for once I sensed an ultimate lack of cumulative

power, and the Passacaglia remained stubbornly remote and its ramifications

not fully explored. In the Burlesque finale thereís a little smeary

tone and the CD tracking has gone wrong Ė it should be track 7 but is

actually tacked as part of the Passacaglia. A small point.

This is a document then of real historical interest.

Itís a small but valuable legacy of preserved concerto performances

by a musician of stature. His association with Stevens is of outstanding

import; Scherchenís involvement with the Berg is a commanding historical

detail; the Bartok preserves one of its earliest British performances.

Rostal may not have become the international soloist it seemed possible

he would but he more than discharged his debt and obligation to Carl

Flesch in advancing performing standards, embracing new repertory and

stimulating composition in a lifetimeís devotion to music.

Jonathan Woolf