The shade of Sergei Bortkiewicz is in the debt of Bhagwan

Thadani, Raymond Oke and Malcolm Henbury-Ballan just as much as that

of Gustav Jenner is to Professor Horst Heussner (see the recent CPO

boxed set of the Jenner chamber music on CPO 999 699-2). I owe it to

Mr Thadani that the sound of these two works was not completely unfamiliar

to me. I enthusiastically reviewed

Mr Thadani's and Mr Oke's CD of the sequenced simulation of these

two symphonies back in 1999. That was a case of faute-de-mieux but even

so the dynamic and vivid qualities of this music shone through the ersatz

sound quality.

Mr Thadani has recorded privately the complete surviving

piano music of Kharkov-born Bortkiewicz and many of the orchestral scores.

His and Raymond Oke's simulations using computer programmes and sampled

orchestral sounds have been the key to opening up these scores to today's

audiences.

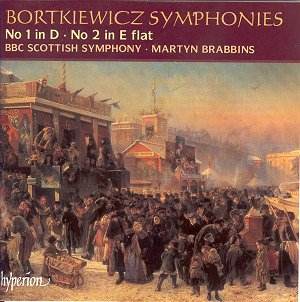

The First Symphony (From my homeland)

declares, through its title, a remembrance of his Russian homeland recalled

from the leafy chaussées of Vienna. The work is fluently Tchaikovskian

with much aching nostalgia, upheaval and flighty comedy. There are Glazunov-like

tumbling high spirits in the scherzo and in the Allegro Vivace finale.

The scherzo resonates with the pizzicato movement of Tchaikovsky's Fourth,

with his Rococo Variations and with the finale of the Third Suite.

Russian Orthodox chant broods gloweringly through the Adagio

which also takes time to include reminiscences of the nostalgic yearning

of the first movement. The finale synthesises a wonderfully aspiring

Slavonic theme, typically Borodin in its topography, and marries it

with the Miaskovskian minatory voices of the abruptly imperious opening

of the work. This movement triumphantly rings the changes in a metamorphic

tumult of Glazunov-like victory (symphonies 5 and 8), imperial splendour

(1812) and Tchaikovskian melodrama (symphony 4).

The blindfold test might well place this symphony circa

1900 (if not earlier). On the evidence of the title you may expect music

which is relaxed and nostalgic but prepare yourself for drama too; especially

in the outer two of the four movements. This is most assuredly nostalgic

stuff but the edges are unsoftened, the drama is vivid and excitement

is built by a musician whose reverence for Tchaikovsky is clear. The

title may prepare you for the pictorialism of Raff or Rubinstein; the

music is quite other.

Bortkiewicz proves himself the Tchaikovsky disciple

again in the Second Symphony. This is even more urgently impassioned,

sullen and angry than its predecessor. It is often exciting, drawing

on the wellsprings of Tchaikovsky (Symphonies 4-5 and Francesca)

without being a pallid facsimile. The andante sostenuto is akin

to the final movement of Tchaikovsky 6 and builds a lapel-gripping atmosphere.

The finale sustains the excitement but its angst reacts with the same

impulsive Borodin-like music as appears in the finale of No. 1.

The silky sheen of the strings is pretty well put across

by the Scots; not that I cannot imagine it sounding even more sumptuously

radiant in the hands of say Ormandy and the Philadelphians or Mravinsky

and the Leningrad Phil had there been world enough and time in the 1960s.

The Scottish brass are gloriously hoarse and insistent.

Brabbins handles this music very well indeed and surely

we can look for him to be at the helm when Hyperion record Bortkiewicz's

Piano Concertos 2 and 3, the meaty Tchaikovskian Cello Concerto and

the much lighter Violin Concerto (the latter a forgotten travelling

companion to the Glazunov).

This disc has sprung onto the retailers' shelves with

astounding speed. The recordings were only made in February this year!

For those who use mind-maps you can place this disc

as a further dactyl off the limbs that carry recordings of Borodin's

Second Symphony, Tchaikovsky's 4 and 5, Glazunov's 4, 5, 6 and 8, Kopylov

and Arensky (better than Arensky and quite as good as the neglected

Kopylov on ASV) and Rachmaninov 2 and 3.

Documentation is what you would expect from this source:

encyclopaedic, well informed and laced with the adventurous spirit of

an investigative archivist. The author is Malcolm Henbury-Ballan, an

Indiana Jones of the world's music libraries. He it was who, by a chance

discovery, traced the scores to the Fleisher Collection in Philadelphia

where, more than half a century ago, Bortkiewicz had deposited the scores

and parts for safe-keeping.

'I can't wait to hear this with a real orchestra.'

So I wrote in 1999. Now we have my wish and handsomely delivered too.

Roll on the later Bortkiewcz instalments ... for surely they

will come!

Rob Barnett

BACKGROUND

Mr Thadani at Cantext Publications, 19 Laval Drive, Winnipeg, Canada

R3T 2X3. e-mail: bthadani@hotmail.com.

should be able to provide you with copies of CDs of his realisations

of the three piano concertos, the cello concerto and the violin concerto.

You could also ask for his 1996 translation (from the German) of Bortkiewicz's

autobiography.

The Bortkiewicz Society can be contacted at: bortkiewiczsociety@hotmail.com