The Fourth is probably the best of Rubinstein’s Symphonies.

Written in 1874 it’s a deeply uneven and ultimately unconvincing work

but contains enough perplexing turbulence to elevate it far beyond the

merely decorative, beyond the post Mendelssohnian symphonic statement.

If it never reaches the heights of a genuine Romantic crisis symphony

it contains intriguing material sufficient to warrant more than a second

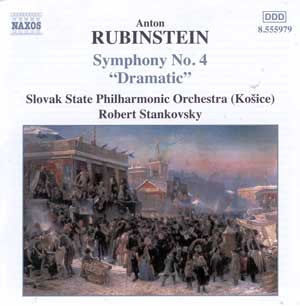

hearing and this Naxos issue, first issued on Marco Polo 8.223319 in 1991,

provides just such an opportunity.

The First Movement opens with angular and forbidding

string writing. A more exultant theme enters followed soon by a compelling

species of orchestral winding-down before an explosion in a unison string

outburst of genuine outpouring – a moment of deeply remarkable writing

and one that seems to strain the symphonic form in which it is housed.

Striving and eloquent strings follow, over a dancing pizzicato, as Rubinstein

tries out his theme in differing orchestral colours and guises. Certainly

the thematic material is over-repeated and it’s also somewhat underwhelming

in its melodic presumptions but there are some marvelous touches – at

17’50 for example where the delicacy of the string writing shades into

solos for flute, clarinet and bassoon. The conclusion of the movement

reveals a little orchestral untidiness from the otherwise well-equipped

Slovak Orchestra. The Presto contains some very oppositional writing

though nothing as volcanic as the earlier movement. From stern unison

string writing and mellow winds some jovial violin figures lead onwards

to lashing animation and a melody of decisive force – the solo violin

passage over ostinato basses adding another voice to the rich orchestral

patina. Some of this is rather reminiscent of Raff and early Dvořák.

The Adagio is a freely moving slow movement in which

strings and wind vie for dominance. The long string melody – attractive

and persuasive – is later enlivened by exchanges between flutes and

the warmth of the divided string section. The finale picks up the quivering

angularities of the opening movement. Its turbulence is a classical

mirror of the First Movement’s divergences and disjunctions. Piccolo

is prominent, fractious brass increasingly so; a sturdy second theme,

in F Major, and a wind episode are both of charming vivacity and impel

the conclusion, which is both colourful and confidently triumphant.

A decade on the Slovak State Philharmonic performance holds up well;

some imprecision, a lack of string heft sometimes. But Stankovsky has

a good sense of the trajectory of Rubinstein’s imaginative writing and

guides us well and resolutely. There is at least one rival – Russian

Disc RDCD 11357 with the Russian State Symphony Orchestra conducted

by Igor Golovchin and released in 1995, which I’ve not heard. But Stankovsky’s

is a welcome return to the catalogue at budget price and heartily recommended.

Jonathan Woolf