|

|

Search MusicWeb Here |

|

|

||

|

Founder:

Len Mullenger (1942-2025) Editor

in Chief:John Quinn

|

|

|

Search MusicWeb Here |

|

|

||

|

Founder:

Len Mullenger (1942-2025) Editor

in Chief:John Quinn

|

|

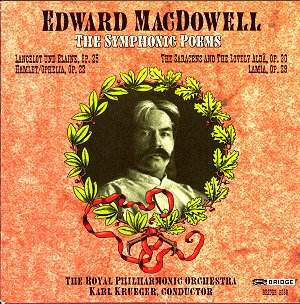

Edward MACDOWELL (1861-1908) |

|

Crotchet AmazonUK AmazonUS |

|

MacDowell’s interest in big orchestral works was relatively brief – no more than seven years – and concentrated between 1884 and 1890, the years during which he wrote the works recorded here. All were begun whilst he was living in Germany, in Liszt’s indomitable shadow and strongly influenced both by him and by Wagner. MacDowell was, in any case, well placed to adapt their descriptive procedures to his own, somewhat less grandiose, ends. This Bridge issue of 1966 performances recorded in London reverses the chronology by presenting the Roland Fragments first. Originally intended as the inner movements of a projected four-movement symphony they were to take their place as part of the wider panorama of the Song of Roland but the surviving movements show how well MacDowell combined technical, expressive and melodic material in pursuit of his ambitious schema. The first of the two Fragments, The Saracens, is saturated in Wagnerian feeling. Martial, with muted brass and aggressive, animating pizzicati MacDowell is fully in command of his material, deploying and redeploying it to strategic effect, the waltz-like contrastive central section acting as a kind of sonata form. In the second Fragment, The Lovely Aldâ, these processes and procedures become somewhat more explicit in their conflict of diatonic and chromatic thematic material – which is not to say they are brazenly obvious, more that he tries to imply changed emotional states through the use of minimally changed thematic material. |

|

Return to Index |