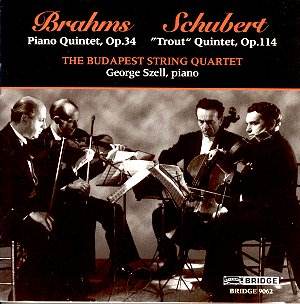

Archive recordings made in the Coolidge Auditorium

of The Library of Congress have been appearing with commendable regularity

over the last few years. Many feature the resident quartet, the Budapest,

and this coupling gives us in addition the impressive piano collaboration

of none other than George Szell, here returning to the days of his prodigy

youth.

Founded in 1918 by the time of these recitals at the

Library of Congress, which began in 1940, the Budapest had altered out

of all recognition. The three Hungarians and one Dutchman, Hauser, Indig,

Ipolyi and Son had, following defection, resignation, retirement and

general hounding resulted in the all Russian formation of Josef Roismann

(still with the double n) and Alexander Schneider, violins, Boris Kroyt,

viola, and Mischa Schneider, cello – though it must be pointed out that

in this recital Alexander – Sasha – Scheider was on sabbatical, having

joined the Albeneri Trio and founded his own chamber groups. In his

place came Edgar Ortenberg, like leader Roismann, Milstein, Oistrakh

and many others a pupil of Stolyarsky. He was to forge a small but select

solo discographic career for himself – the peak of which was his fine

recording, with Lukas Foss, of Hindemith’s Third Sonata of 1935 on the

small Hargail label.

The sound on these performances varies from excellent

to patchy, though very much more of the former and the Brahms, fortunately,

is notably better recorded than the Schubert. The success of the works

varies as well. The Brahms is in fact an auspiciously fine performance,

without mannerism and, better still, little dichotomous inclinations

from either quartet or pianist. The Quartet’s charactertically lean

sonority is put to splendid use. The opening movement flows with pliancy

and conviction; phrasing is elegantly if perhaps a little coolly expressive;

no obstacles, rhythmic or thematic, obstruct the longer line. Roismann

and Ortenberg are especially chaste in the Andante, striking a notable

balance between movement and reflection, whilst the stomping and rhythmically

galvanised Scherzo is conveyed with the maximum of surging energy and

the minimum of instrumental problems. They catch the winding rather

austere introduction to the Finale with genuine understanding and subsequent

incidents – crisp accents, charm and real humour (the Budapest are generally

much more witty live than in the studio) reinforce their comprehensive

control of the work. Szell is a most sympathetic and astute collaborator

– he was to record Mozart with them commercially – and the performance

as a whole most impressive.

Shock, horror – track five is three minutes and fifty-one

seconds of George Szell’s humour. In distinctive American inflected

vowels this Central European tyrant chats about the ubiquity of the

bass tuba in acoustic orchestral recordings, Max Reger’s huge teaching

classes and that pedagogue’s tendency to tell dirty jokes in public.

He also reminds us that he was a child piano prodigy and studied composition

with Foerster. Doubtless not reflections he passed on to the members

of the Cleveland Orchestra over a soothing cup of tea.

The Schubert is alas a disappointment after the Brahms.

Roismann, Kroyt and Mischa Schneider collaborate with Szell and bass

player Georges Moleux. The sound is not awful but there is a recessive

quality to it and there are some little audible ruptures in the acetates

– though continuity is maintained and those ears accustomed to live

performances of this kind will be quite used to such things. Harris

Goldsmith, an excellent annotator who fuses erudition with judgement,

is more than a little circumspect when he refers to this performance

that he rightly characterises as one that "expunges….the gemütlichkeit…"

from the music as well as some superficially unattractive slowings down

in the Andante – they sound like the huge rallentandos that routinely

ended a 78 side. In fact the performance isn’t really thought-through.

Too many peculiarities attend to the fabric of the playing, the Theme

and Variations is rather badly disfigured by scrabble and scratch, and

it also emerges as rather lumpenly phrased. Not uninstructive to listen

to but best to stick to the Brahms.

A variably successful recital but most refreshing to

hear Szell’s idiomatic and subtle Brahmsian collaboration and recommended

for that reason – and the Regerian quips of course, as well.

Jonathan Woolf