This record groups together the last songs of Schubert

and Brahms, though I think it would be over-ingenious to find any particular

points of resemblance between them other than that. Readers who are

still exploring the world of the lied should know that "Swansong"

was not Schubertís title but the publisherís (the songs came out posthumously).

Nor do the songs form a cycle by telling a story as Die schöne

Müllerin and Winterreise do. They consist in fact of

two groupings and a single song Ė 7 songs texts by Rellstab, 6 with

texts by Heine, plus Die Taubenpost. It is worth remembering

that to group songs together according to the poet set was in itself

a new departure for Schubert, and maybe for the lied generally. The

Rellstab group revisits familiar Schubertian images of brooks and fields,

all suffused with the deepest longing for a distant beloved. The terrain

may be familiar from other works by Schubert yet it perhaps finds its

sublimest expression here. The encounter with Heine took Schubert into

unprecedented dramatic territory. The two groups are therefore unrelated

but perhaps Schubert felt each complemented the other since he offered

them to a publisher together as a cycle. The publisher, as said above,

brought them out the year following Schubertís death under the title

that has remained ever since and added to them Pigeon Post, Schubertís

last song of all. This relatively light-hearted piece sits strangely

after the Heine settings, but in a fine performance it can impress as

a bittersweet remembrance of happier times.

Brahmsís Four Serious Songs was his last completed

opus, though his op. 122, the 11 Chorale Preludes for organ, lacked

only the last refinements of dynamics and so is not really to be considered

an "unfinished" work. As a Bible student Brahms was as sturdily

independent as he was as a musician. The final song sets St. Paulís

great text, "Though I speak with the tongues of men and angels

Ö" but in the others he shows an awareness of the remoter corners

of the sacred books, including the Apocrypha, seeking out passages which

speak of the bitterness of death and the transience of life. This sounds

pretty grim, yet in the hands of an artist like Kathleen Ferrier these

songs have brought consolation to generations of listeners.

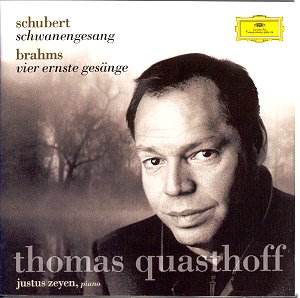

Thomas Quasthoff has a growing reputation and proves

a natural lieder singer. His voice is an attractive one, warm and sonorous.

Its lower range seems not great Ė the low Aflat in the first part of

In der Ferne disappears long before its written length has been

exhausted. Why not sing this sing this song a semitone higher? His upper

range is firm and rounded. One or two piano Fs are sung with a trace

of head voice but this seems a choice rather than a necessity and by

and large he makes little recourse to this dubious practice. Sometimes

in long notes his tone begins a little huskily and acquires its true

colour later Ė certain vowels seem to provoke this. Examples can be

found in Aufenthalt with the words Tränen and brausender.

His singing of the first page of Der Doppelgänger is really

too exaggeratedly pianissimo. I donít know what anybody would hear in

the concert hall Ė even the microphone has difficulty in picking anything

up!

Still, these are small matters. Unfortunately I have

a whole sheet of gripes about the pianist. The demi-semiquavers of Liebesbotschaft

are not clear. This is not Debussy and Schubert requires transparency.

The chords on the third beat of most bars in the outer sections of Kriegers

Ahnung are quavers followed by a quaver rest but they are not actually

staccato and Zeyen bumps them unmusically. The rests at the beginning

of In der Ferne are not always counted out correctly. When the

triplets start on the second page of Der Atlas the rhythm becomes

clear only after two or three bars. In the chords which pervade Die

Stadt (the figure is heard for the first time in bar 3) the middle

notes are stronger than the upper note not just once, which might be

an accident, but every time, which begins to look like carelessness,

as Oscar Wilde would have said. Yet the point of Schubertís accents

is surely that the falling octave is to be heard melodically. All this

pales into insignificance before what happens in Ständchen.

The quavers are chunky, but let that pass. At the end of the singerís

first phrase, which Quasthoff rightly sings very simply, the piano echoes

his last two bars. ECHOES, I said. But no, Zeyen inserts a big expressive

comma, as though to say, "Listen chaps, now IíM going to do it",

then he splits his right hand chord and plays the phrase with lavish

Cho-pansy rubato. This is outright vulgarity and is in itself enough

to exclude the disc from any serious consideration.

In view of this it is hardly worth adding that Die

Taubenpost is actually rather enjoyable and the more generalised

romantic pianism of Brahms suits Zeyen better. But put on that Ferrier

record and you will immediately hear a tingle factor which Quasthoffís

well-schooled singing just canít match. The message is all in the last

song. Ferrier could sing with the tongues of men and angels but she

also had that extra quality which might be called love or compassion

and which somehow brings a lump to the listenerís throat many, many

times during the performance. The trouble is that if you can only sing

with the tongues of men, you can sing quite nicely about birds and bees

and flowers, but songs like this will not yield up their secrets and

will only match E. M. Forsterís description of them in "Howardís

End" as "grumbling and grizzling".

There is no shortage of famous versions of Schwanengesang

and youíd be better off with any of them. Itís getting to be a stale

truism, but if youíre new to lieder youíre still safest with Fischer-Dieskau.

Christopher Howell

But

Melanie Eskenasi thinks totally differently