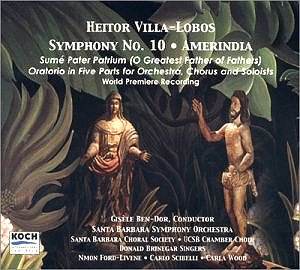

With CPO currently about halfway (at least numerically)

through their cycle of Villa-Lobos’s twelve symphonies, this release

from Koch of the largest, the choral-and-orchestral Tenth, is most timely.

Written to mark the 400th anniversary of the founding of

the Brasilian capital, São Paolo in 1552, it was first performed

in Paris five years later under the composer’s baton in an apparently

typical ramshackle performance. That it was not well received is unsurprising,

even if the performance had been as well drilled as that on this new

recording. It is an occasional work out of its time, in annotator Steven

Ledbetter’s words "a kind of musical history lesson" that

cannot have had much relevance to a Parisian audience in 1957. Written

in a style more redolent of film music, as a novelty it must have seemed

desperately anachronistic when compared to other new music of the day.

The work’s structure cannot have aided its appreciation,

being as much an oratorio (which can go under the title of Sumé

Pater Patrum, ‘O Greatest Father of Fathers’) as a symphony, neither

form in vogue critically. The symphony centres on the huge 24-minute

fourth movement De Beata Virgine Dei Mater Maria, a kind of suite

in four sections functioning like a work-within-a work. For the most

part the music sets extracts from a huge poem by Father José

de Anchieta depicting the arrival of the Portuguese, their joy at discovering

the teeming continent, expressed in praise of the Virgin Mary and their

rejection of Protestantism, expressed as an image of an Infernal Dragon

representing "death-bringing Calvin". Like so much of Villa-Lobos’

orchestral output, the music is richly illustrative but here the crucial

dramatic event—the concluding "Infernal Dragon" section—seems

underplayed by the very richness of the palette he used.

For all its weaknesses structurally and dramatically,

the Tenth Symphony is a fascinating piece, full of remarkable music

instantly recognisable as Villa-Lobos. The opening allegro, The Earth

and its Creatures, is perhaps too long for its material and as with

many of his symphonies, symphonic development is only fitfully present.

The succeeding War Cry is wistful and gentle, a "lament

for the lost tranquillity and isolation of the countryside" to

quote Ledbetter again rather than a call to arms of the native populace

to resist the Portuguese. (And as a descendant of the conquerors, whether

or not there is any truth in any of the composer’s outrageous claims

to Amerindian origin, Villa-Lobos always presented the arrival of the

Europeans as a good thing; the Indians’ rather different perspective

would not, I suspect, ever have occurred to him.) It is the first to

feature voices, and has more vigorous central sections that sound straight

out of the Bachianas Brasileiras, as does the third movement,

a celebratory scherzo subtitled Iurupichuna (a species of small,

magical monkey). The fifth and final movement, Glory in Heavens and

Peace on Earth, is more fully choral (like the fourth) and continues

to set extracts from Anchieta’s poem. Its unquestioning affirmation

may strike many listeners as a touch hollow, but it is hard to see how

else this large work could reasonably have concluded. I feel bound to

comment also that the choral writing does not contain the same subtlety

as do the works of Hyperion’s wonderful CD of Villa-Lobos Sacred Choral

Music (CDA 66638).

Gisèle Ben-Dor, who has previous conducted some

revelatory recordings for the same label of Ginastera (3-7149-2) and

Revueltas (3-7421-2), secures a committed and full-blooded account of

this teeming and problematic score. (She also provides a highly informative

note on the difficulties the music presents to a conductor.) The three

soloists and the amalgamated choruses sing with more energy than refinement

(entirely appropriate for this repertoire, however) ably supported by

the Santa Barbara Symphony Orchestra who are the real stars of the show.

Never a disc or a work to win competitions or great plaudits, perhaps,

that should not detract from what is a splendid achievement all round.

Self-recommending to lovers of this composer (I count myself for one),

it is certainly worth exploring by those who know him only for the Bachianas

Brasileiras.

Guy Rickards