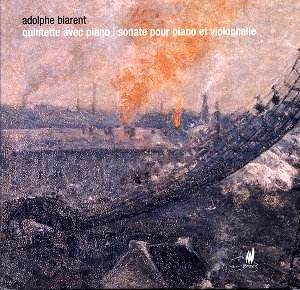

A rich palette with infinite shades of colour. A

description from the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Charleroi of the

work of the painter Pierre Paulus (1881-1959), one of whose industrial

landscapes graces the cover and booklet of this ravishing and beautifully

produced disc. How appropriate then that Charleroi-born Adolphe Biarent,

himself a colourist of gifts, should have devoted himself to the promotion

of music in the town, to the establishment of symphony concerts there

and the nurturing of instrumental talent. Whilst it’s true that both

Ysaye and De Greef played some of his music Biarent’s profile remained

stubbornly local and his influence merely peripheral. He died of a cerebral

haemorrhage in February 1916 aged forty-four.

Stylistically he shares something of the Lekeu hothouse

and the expected influence of Franck remained almost unavoidably pervasive,

though utilised to Biarent’s ends, and diffused through awareness of

and consonance with Russian influences. Franck’s 1879 Quintet and the

Violin Sonata were nevertheless strongly influential and pervade both

works on this splendidly thoughtful disc. Biarent was himself a cellist

of standing and an experienced chamber player – he trained, amongst

many, Fernand Quinet, later to found the celebrated Pro Arte Quartet

– and clearly as accomplished a composer for smaller forces as he was

in the larger canvass. The B Minor Quintet was composed in 1913 and

slightly revised during May of the following year. In three movements

it’s notable for a compressed but intense sense of flux – chromatic,

harmonic – in which an initially dominant piano, fractious and controlling,

gradually responds to the pliant entreaties of the strings leading to

a reconciliation and sense of evolving balance. It is most impressive

to listen to the way in which Biarent introduces the first violin’s

songful openheartedness, underpinned as it is by the piano’s now rippling

figuration. Much here is sectional but the motivic conviction with which

Biarent handles his material is consistently convincing and if, at moments,

it’s hard not to think of the Franck Violin Sonata (at, for example

9’45 in the first movement) there is so much profusion of incident,

so agitated and adventurous, that one soon allows such moments to absorb

themselves into the bloodstream of Biarent’s syntax. If in doubt, listen

to the exhausted calm of the B major ending of the movement. The slim

central scherzo opens with an ominous piano figure; it catches and distils

the convoluted unease of the first movement before all suddenly becomes

flecked with gossamer fleetness, and with wit and energy – but always

cyclic cohesion – Biarent prepares the thematic ground for the concluding

finale. This reasserts the initial density of argument in which strident

declamation and moments of lyricism co-exist, almost oppositionally

presented until increasing resolve and confidence lead to the overwhelming

conclusion. Much of this would seem to suggest that Biarent was obsessed

by binary oppositions and that the Quintet is a construct along those

lines; not so, however. It is an intensely dense work which conceals

within it elements of Franckian cyclic introversion but which is also

lit from within by colour and vivacity. It is a restless, emotional

work, superbly interpreted by the performers who catch its unsettledness

and unease unerringly.

The Cello Sonata followed the Quintet and its composition

mirrored the first anguished months of the War. Begun in October 1914

it was finished in April 1915 and is in four movements. Its yearning

profile is precise and focused – there is a proper sense of striving

and release in the first movement, reflective but not slavishly imitative

of the language of the late Romantic sonata. Again its axis is undeniably

Franckian. The sense of a final lack of resolution as the first movement

ends is a distinctly Biarent one – he prefers lack of conclusiveness,

reduces the hermetic structure of movements, uses cyclic structures

to flood his chamber works with interlaced detail. His obsessive nature

is shown by the cat and mouse violence of the second movement presto

furioso and the immediately following concise rumination of the

slow movement. At 3’35 this is concision itself – the notes by Michel

Stockhem are very thoughtful, by the way, and speak of the movement

as encapsulating the first winter of the War in its entirety here, a

judgement with which I rather disagree. Rather it seems to me that the

internal violently opposed inner movements are as reflective of Biarent’s

compositional dilemmas as they are of external circumstances and take

them, indeed, to structured extremes. The cyclical impulse is magisterially

evident in the final movement which revisits earlier thematic material.

The muted cello solo is a moment of decisive intimacy accompanied by

a reflective-romantic piano; the gentle, sorrowful cello ends the work

with a resigned pizzicato. This is beautifully negotiated by Marc Drobinsky

and Diane Anderson and I have little but praise for them – maybe Drobinsky

is rather nasal in the upper strings and I felt too boomy in the lower

two. In the first movement I felt he could have infused his line with

more shades of vibrato and at slightly more varied speed but he is a

sensitive and athletic musician and this is a convincing performance.

Try to seek out Biarent. The teeming industrial cityscapes

of Pierre Paulus have their musical equivalent in Adolphe Biarent. In

these chamber works and in these performances the fires lit are thick

and dense but glow red hot at their core.

Jonathan Woolf