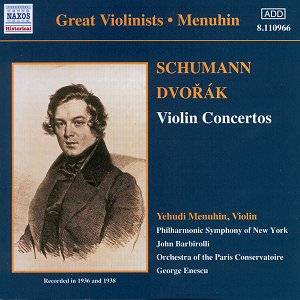

The first thing to notice about this latest release

in the Naxos ĎGreat Violinistsí series is the cover portrait. Not, as

expected, that of the ostensible hero of the disc, Yehudi Menuhin, unlike

all the others in this and the allied Great Pianists series that I have

seen where the soloist is dignified with a picture. This CD instead

features Kriehuberís 1839 portrait of Schumann. Is Menuhin still too

much our contemporary, too newly dead, or is this a new Art Work aesthetic

from Naxos?

Whatever the reason here we have two recordings from

Menuhinís golden youth Ė the DvořŠk

recorded when he was not yet quite twenty and the Schumann from almost

exactly two years later. The Schumann was the subject of well-known

international musico-political posturing of a faintly ludicrous stamp.

The rediscovery of the Concerto in 1937 quickly became an issue

of spiralling absurdity when its existence was supposedly revealed to

Jelly díAranyi during a séance and a premiere with the BBC Symphony

and Boult was announced. Meanwhile a performing edition was being prepared

by Georg Schunemann and Paul Hindemith based on the unpublished score

in the Prussian State Library. Menuhin became interested as well, having

been sent a photostat. In the event, after much intrigue and several

postponements the first performance was given by Georg Kulenkampff followed

a little later by Menuhin in St Louis, though heíd played it in New

York with piano accompaniment and had, I believe, already run through

it privately with senior colleagues and teachers there. DíAranyi did

eventually give the first British performance but not until the following

year. Tully Potter misses a few tricks in his sleevenotes concerning

the work and its reception Ė Menuhin, whilst on tour in Richmond, Virginia,

actually heard the first broadcast by Kulenkampff, which was broadcast

at 6 am apparently Ė the soloist, he noted, "was not the first

brand." In addition all three interpretations have survived to

a greater or lesser extent. Menuhinís and Kulenkampffís are well known

but díAranyiís

February 1938 performance was broadcast and the slow

movement was recorded, albeit imperfectly, on glass nitrate discs by

an enthusiastic amateur recorder.

The Schumann opens in rugged and determined fashion

with fine sectional discipline under Barbirolli. At 5í55 Menuhinís playing

is vibrant, his vibrato intensely expressive and inflective, his dialogue

with the clarinetís arabesque figure delightfully impressive before

the oboe takes up the figure and the violin muses on it. Menuhin brings

a sweetness but also a strength to the passagework here and his tonal

reserves are admirably deep. In the slow movement it is the sheer intensity

of his playing that is so noticeable, his lower strings husky, his upper

strings passionately vibrant and there is here a communion of sensitivity

between orchestra, conductor and soloist. The finaleís occasional weaknesses

are well concealed by the vivacious playing. Menuhinís musicianship

is admirable Ė beautifully equalized with a trill of electric velocity,

whilst Barbirolliís direction of the horns from 8í02 is equally impressive.

He conducts with adroit musicality and surety of architectural delicacy.

Not even they can quite overcome the relatively weak ending though.

Menuhin had first practised the DvořŠk

in 1929 according to Humphrey Burtonís recent biography of the violinist

so he was not surprised by it when he made the February 1936 recording

with the guiding hand of George Enescu. Itís quite true that this is

a significantly less impressive recording than the Schumann.

The opening orchestral tutti for example is damagingly weak in relation

to Menuhinís entry, despite the violinistís delicious tonal colouration

here from 3í50. The orchestral winds remain distant throughout the performance

and behind the solo violinís passagework in particular where they are

inaudible. The Parisian orchestraís bass section also sounds dull, an

impression doubtless magnified by the recording and at 7í35 there is

a stolidity to the rhythm that impedes and retards momentum, even though

Menuhinís subsequent outburst is passionately convincing. The slow movementís

impact is again vitiated by recording problems Ė there are some attractive

but very distant orchestral solos as well as much fluent playing, though

not really idiomatic enough. The opening tutti of the final movement

is nowhere near as vigorous as it should be or as lilting Ė there is

a definable rhythmic cell missing from a performance of this kind and

it makes its absence most apparent here. The stubbornly intractable

bass line also doesnít help and Enescu canít stop the result sounding

stiff. Even Menuhin fails to flourish here.

Iím rather disturbed by the tone of some of Tully Potterís

comments. His status as Adolf Buschís Representative on Earth is well

known but the corollary is insinuating antagonism toward Kulenkampff,

Buschís German rival. Furthermore his assertion that the Schumann was

the finest of all Menuhinís pre-War Concerto performances will not be

shared by those who admire the Elgar, Paganini No 1 and Symphonie Espagnole,

amongst others. But I strongly recommend the disc, well transferred,

especially if you lack the Schumann.

Jonathan Woolf