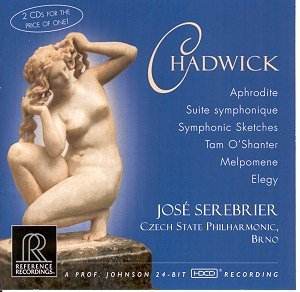

Reference Recordings have show real fidelity

to the creativity of Jose Serebrier.

Not only that they have encouraged him in some tangy and imaginative

repertoire but now some of there earliest projects are being reissued

as twofers. They have also gone the extra mile and issued the two Serebrier

Janáček CDs in the same way on RR-2103CD.

There was a time when the names of Coerne, Parker,

Chadwick, Gilbert and Beech meant hardly anything except to the dedicated

musicologist. These figures were from the North American musical renaissance

of the period 1880-1920. They had their meed of success during their

lifetimes but after that oblivion swept their works into the cobwebbed

corners. A similar thing happened to Mackenzie, Tovey, Stanford and

Parry.

Neglect was not complete. There are always exceptions

and in the world of recordings there have been a few. During the 1960s

the Society for the Promotion of the American Musical Heritage (SPAMH)

issued many LPs featuring Chadwick and his contemporaries. The names

of Karl Krueger and the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra (along with the

MIA LP prefix) will always be associated with that series. Bridge are

gradually reissuing that series on CD. Howard Hanson on Mercury recorded

a number of these works during the 1950s. In the 1970s the conductor

Kenneth Klein conducted the LSO in an intriguing US renaissance collection

for EMI. More recently Albany and Chandos (the latter with the Detroit

SO and Neeme Järvi) have been exploring this repertory. Paine’s

two symphonies have been recorded by New World with Mehta and the NYPO.

Chadwick was forced to leave high school early but

through dedication and long hours of study completed studies in literature,

history and German. Disinherited by his family he left America and studied

with Jadassohn and Reinecke in Leipzig. Later he worked with Rheinberger

at Munich. After three years on the Continent he returned to the States

on the staff of the New England Conservatory finally rising in 1897

to the position of Director.

By 1893 he had composed had three works named and numbered

as ‘Symphony’. A further three multi-movement symphonic scores were

to follow: Symphonic Sketches (1895-1905), Sinfonietta in

D (1908) and Suite Symphonique (1910). The first and last are

recorded on this pair of discs.

Symphonic Sketches is in four movements;

each picturesquely titled. Jubilee

is Dvořákian and has an eager energy reminiscent of the more demonstrative

portions of Dvořák’s Fifth and Sixth symphonies. At 3:50 coincidentally

a little fanfare figure sounds as if it might have been written in tribute

to the New World Symphony. Chadwick

is a master coiner of fine themes (try the one at 4:20) and Jubilee

ends in blazing glory with savagely sonorous brass. Noel is the

second movement and summons, through some ripely romantic string and

woodwind writing, the spirit of a child’s Christmas. Chadwick’s son

(named Noel) was born a year before he started work on this movement.

Hobgoblin with its dancing woodwind is the least substantial

of the four movements. The side-drum and xylophone are used very effectively

in a Vagrom Ballad reflecting Chadwick’s experience of seeing

a down-and-outs encampment. The moods flit and transform constantly.

At 6.00 there is a very serious string statement imbued with romantic

passion. The movement ends in crashing grandeur which seemed rather

dutifully grafted on to an otherwise intrinsically very attractive work.

The Melpomene overture is Tchaikovskian; well

if not Tchaikovsky then perhaps Glazunov. In the introduction it is

rather like Romeo and Juliet although it lacks the world-conquering

themes of the Tchaikovsky work. Instead it has a Brahmsian darkness

and some gloriously liquid Slavonic horns at 9.03.

Tam O’Shanter is a major discovery. Banish

Arnold’s fine comic overture from your mind. This is a serious fantasy

symphonic poem. Gales are invoked, horns cut excitingly through the

texture and there is some really fine brashly vivacious writing for

the horns. Other notable signposts include the sound of woodblocks which

registers exotically in a wild dance. This is not a comedy overture

rather it reflects Mussorgsky’s Night on the Bare Mountain

and the highly coloured poetry of Rimsky-Korsakov. Although there is

a slight skirl and some Scottish flavour there is, thankfully, no music-hall

Tartan in this music. The work ends in Dvořákian repose.

The second disc plays for almost ten minutes longer

than CD1. It opens with the Symphonic Suite. This time there are no

gaudy titles for the movements apart from the usual temperament indications.

Again the music is rhythmically inventive and varied with some blastingly

devastating brass writing. The movement (allegro) ends in heroic tumult.

A relaxed Romanza follows with a prominent part for saxophone. The third

movement Intermezzo and Humoreske is rhythmically very engaging

in a Tchaikovskian way perhaps like Hakon Børresen’s first symphony

(available on CPO and Marco Polo). The finale deploys the xylophone

and has a stamping grand symphonic conclusion. This is a work (and a

performance) of distinction, excitement and allure.

The sensuous and the erotic are not what may be expected

of the American East Coast school. However in his half-hour symphonic

poem Aphrodite Chadwick has learnt from Franck’s Psyche,

a work with which the Chadwick piece has many affinities. The Easterner,

from a sternly religious family milieu, has absorbed a Californian approach

to life. This is the most voluptuously French piece on the two discs.

You can hear the water lapping the shore and all too easily be drawn

into a scene from a Mediterranean fantasy by Alma-Tadema. The piece

has a good deep-sea theme, foam flecked and wave crashed, breathing

blue-green romance. It has many moments of quietly sensuous poetry and

Track 9 is of outstanding beauty.

The Elegy for Horatio Parker is quietly passionate

without too much all-purpose ‘nobilmente’. It has a sense of anger at

loss which tells us that Parker and Chadwick were close friends. This

is no formal tribute.

Stephen Ledbetter’s excellent notes are a strength

of this set.

This is warmly recommended for fine rare repertoire

and typically sprung, lively sound with power and subtlety aplenty.

These discs were previously issued separately as Reference

Recordings RR-64CD and RR-74CD.

I trust that Reference have not finally turned their

backs on rare repertoire and I hope they will do more rare and unrecorded

Americana. The field is wide open. Meantime enjoy these discs which

are perhaps the stronger because of the international input: Uruguayan

conductor and Czech orchestra.

Rob Barnett