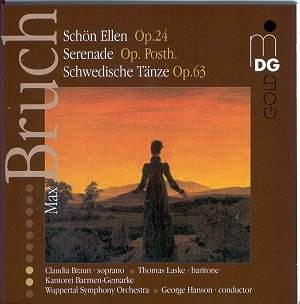

Without wishing to sound patronising, the standards

of German orchestras from the so-called B list of opera houses and towns

are remarkably good. I myself conducted one such orchestra last year,

coincidentally in a festival concert of Bruchís music (well not really

much of a coincidence for I am his only biographer, a source

recognisably plundered by the booklet writer of this CD with regrettably

no due acknowledgement) and I did some of the Swedish Dances to

start the programme, as this disc does. Bruch never meant them to be

played all at one sitting, but one cannot blame a company for recording

all sixteen, even in their original format for solo piano. Hansonís

tempi are sometimes too fast, other times too slow, but his orchestra

sounds fine, especially the woodwinds. Bruch loved the cor anglais and

the player here would surely have pleased him. Hanson does not sentimentalise

the rich melodies but paces and phrases with care yet without losing

forward drive, especially the 13th with its divine solo for

the leader of the orchestra (succulently sweet here). The Dvorak/Brahms

flavour of some of the dances is especially well caught.

The Serenade for Strings is a reworking of a

rather overblown orchestral suite written a dozen years before in 1904,

but though the old man was in his late seventies, isolated and devastated

by the effects of the First World War, he had not his touch in scoring

for orchestra. Itís somewhat of a misnomer for the title here has omitted

the crucial words Ďon Swedish melodiesí and itís just that element of

folk music which so attracted Bruch throughout his life, and itís also

misleading of the booklet writer even to mention the possibility of

any programmatic content, even though she alludes to my assumption that

they were posthumous additions by the unscrupulous publisher Rudolf

Eichmann. It was more than an assumption; it was a fact. Bruchís music

has no need of titles, and this is a work which takes a place besides

Griegís Holberg Suite or Dag Wirénís Serenade.

Hansonís string section does it justice, nicely shaded playing, delicate

or rough-edged tone where required, wide-ranging dynamic contrasts;

in short they give a performance which captures the essence of Bruchís

style through and through, apart from one overdone portamento

in the fourth movement Andante sostenuto. The finale is beautifully

delicate, especially the very end of the work.

Another misnomer on this disc is its subtitle ĎOrchestral

Worksí, for Schön Ellen Op.24 is a choral ballad, for two

solo singers, chorus and orchestra. Here too we are in the realm of

folk music, in this case Scotland for which Bruch held a life-long affinity,

though I can find no evidence that he ever went there. Even so the Scottish

link is tenuous. Set at the Siege of Lucknow in India in 1857 it relates

how Ellen predicts its relief by the regiment led by the Campbells but

her foresight is only because she has acute hearing and can hear the

regimental marching song before anyone else does. The Campbells are

coming therefore features throughout. How one can sing or conduct

this work with a straight face is hard these days, though it helps if

you sing it in German and avoid overdoing the rum-ti-tum nature of its

6/8 rhythm. Claudia Braun pronounces it ĎKembellsí so that helps, while

Sir Edward is rechristened Sir Edvard by the male members of the chorus.

Thomas Laske copes well with the high tessitura of the baritone line,

a feature developed in Bruchís later secular oratorios with Heldenbaritones

in title roles such as Odysseus or Moses. Thereís no other way to present

this style (itís a couple of years to go before the first violin concerto

of 1867) other than the way it was meant and all here, soloists, chorus,

orchestra and conductor, do just that especially at its jubilant ending.

Christopher Fifield