I donít find it easy to write about this, for so much sincere,

honest endeavour has gone into it, yet somehow it seems able to rise above

the ordinary only in the fifth volume. This latter does indeed justify

many of the premises of the whole series so readers are alerted straightaway

that the criticisms I shall have to make of the earlier volumes are not

the whole story.

Angela Lear was encouraged many years ago by her teacher

Louis Kentner to examine the manuscript sources of Chopinís music. Over

the years she has gone on hunting down discrepancies between published

editions and manuscripts and, more lately, has been persuaded to display

her not inconsiderable pianistic skills in a series of recordings which,

it is claimed, are unique in their scrupulous observance of Chopinís

performance indications.

Excessive claims are always dangerous in that they

risk stimulating the opposite reaction. The records come with an introduction

from Colin Pryke which virtually challenges the dissenting critic to

prove he does not have cloth ears. "Among the cognoscenti, Angela

Lear is known as the worldís finest player of Chopinís music" (so,

if you didnít know this, you are ignorant by definition). "The

significance of the research and the attempt to produce exactly what

Chopin required has not always been fully understood or appreciated",

he warns us. Nevertheless, I have to side, at least as far as Volume

Four, with "those critics who have not yet fully appreciated the

importance of this work". Delicious, this "yet". My road

to Damascus may yet be found and, who knows, I may even sit down at

the piano one day and join "those mature artists who are not too

proud to reshape their performances in the light of these important

revelations".

"Those Who" have been a convenient butt of

writers on music over the years. The doyen of opinionated musical analysts,

Sir Donald Francis Tovey, had plenty to say about "Those Who".

To stick with a single example, "Those who find it (Beethovenís

op. 110 Sonata) unimpressive are beyond the reach of advice",

he thundered in his famous edition of the Beethoven Sonatas, and "Those

Who" had a good deal more to answer for than that. The whole tenor

of Angela Learís Chopin series takes issue with "Those Who".

The great thing about "Those Who" is that they are by definition

without a name, yet with the aid of a little rhetoric readers can very

readily imagine them. And so the picture is built up of a rabid crowd

of egocentric pianists and editors who just canít wait to get their

filthy fingers on Chopinís pristine music and manipulate it to their

own ends. But who are the culprits? Who are "those who feel that

some pianists have the ability to improve on Chopinís music"? Who

are "those who seek to improve his work, or who fail to respect

it by using it as a vehicle to display their own technical facility"?

Which are the abominable editions? All of them? We are not told

Itís a funny thing, this business of Chopin editions.

Listen to this: "To indicate all the differences between the manuscripts

upon which Chopin worked and the original editions on the one hand,

and the editions now universally available on the other, would be an

endless labour. But the present strictly accurate edition will suffice

to show to what extent petty minds have at times Ö lowered the standard

of significance achieved by the composer".

Strong stuff. And no, itís not Lear and her collaborators

that wrote this; it comes from the

preface to the Oxford Original Edition of Chopin, dated 1928. And how

about this one: "The principal aim of the Editorial Committee has

been to establish a text which fully reveals Chopinís thought and corresponds

to his intentions as closely as possible". As most pianists will

recognise, this is from the Polish "Paderewski" Edition of

1949, an edition which many still prefer. As this preface goes on to

recognise, "Chopin frequently changed details of his compositions

up to the very last moment", leaving space for a wide variety of

"authentic" texts. A well-known British pianist once told

me that the guiding principle behind certain recent Urtext editions

seems to be that of taking the least musical available reading in every

case.

So the idea that all the printed texts are wrong is

a red herring. The notes do at one point admit that the small differences

between this and other performances are not so much textual variations

but derive from the fact that the egos of many of the great artists

of the past (de Pachmann, Cortot, Rosenthal and Rachmaninov are named)

"would not allow the Composer complete control over his own music.

This was something he fought for in life, though in death he only has

an artist like Angela Lear (and hopefully others following in her tracks)

to seek to maintain his standards".

While it is true that some pianists in the past have

taken Chopin as fodder for their own genius, it is also true that there

have also been many Ė with Rubinstein their leading light Ė who have

believed firmly in Chopinís written scores and have attempted to follow

them. Furthermore, not all those who have taken a freer view have done

so out of mere arbitrariness and many have made their apparent "licences"

in the name of traditions handed down from teacher to teacher and just

possibly going back to Chopin himself (certainly, a number of "historical"

pianists believed this was the case). So just what does Lear have to

offer?

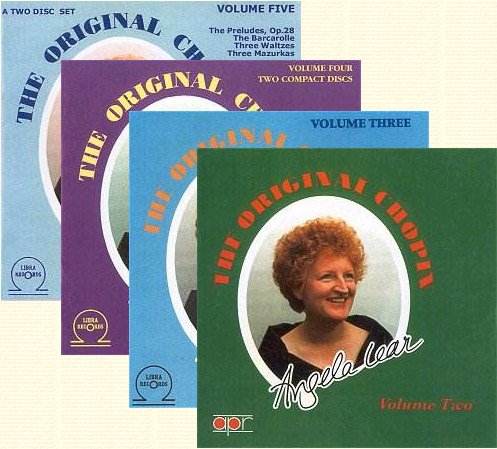

Her series has now reached five volumes, of which the

first two were for the now defunct APR label. Rights to these are now

held by Libra Records, who have reissued Volume Two (Volume One may

be reissued later), and for whom Lear has recorded her subsequent volumes.

VOLUME TWO

I followed the 3rd Scherzo with the score

and I cannot say I noticed any point at which Angela Lear was not following

the Paderewski edition I had in front of me (but here we are: which

are the "wrong" editions and where are they wrong,

exactly?) Ė or at which she was doing so while the likes of Rubinstein

departed from it. Maybe this piece is not an ideal example since it

is not one of those subject to traditional "maulings". The

common aberrations which one might expect to see corrected, given the

premises of the enterprise, are two: firstly, the opening bars are often

played more slowly than the basic tempo, with "creative" interpretation

of the rests; and secondly, when the chorale-like theme is alternated

with gossamer figuration in the upper reaches of the keyboard, pianists

are inclined, given the extreme difficulty of leaping up from the former

to the latter and actually getting the right notes straight off, in

the right pianissimo touch, to take their time in moving upwards, respecting

the alternating character of the two musical ideas but playing

havoc with rhythmic continuity. Both these "aberrations"

are present in Rubinsteinís 1960s RCA recording, if to a lesser degree

than in most other performances. Over both these points Lear is more,

not less, indulgent than Rubinstein. In addition, there is also

a suspicion that while Lear is coping with the notes very competently,

Rubinstein is displaying a wizardry that goes beyond mere notes.

In the Boléro Lear emerges creditably

beside Rubinstein. The differences donít really have much to do with

interpretation or with their basic view of the piece (so Rubinsteinís

is "original Chopin" too?), itís just that Rubinstein is a

better pianist. His open octaves have an "I mean business" air,

his flourish goes up like a rocket and

he separates melody from accompaniment, or points up harmonic changes,

just that little more

The E major Nocturne raises another matter. Learís

melodic line does not particularly sing, and in so far as it is separated

out from the accompanying chords, it is done so by persistently playing

with the two hands not quite together. I always thought this was a bad

old habit, and maybe Rubinstein thought so too, for he certainly does

not do it, nor does he need to since he is quite able to separate the

two strands by colouring them. He is also a little faster, without in

any way contradicting Chopinís Lento marking, and the agitato

section sounds really that, without any hurry, not least because it

produces a myriad of textual clarifications which donít seem to be even

attempted by Lear. As regards the text, I had the Henle edition and

both of them diverged from it in small details. However, I got the impression

that, whatever edition they were using, they both had the same one.

The Henle edition has collected a certain amount of flak, but inventing

pedal markings was not on its agenda so what is the authority for the

surely effective long pedal in the third and fourth bars from the end,

ignored by both Rubinstein and Lear?

Without going into all the numerous comparisons in

the G minor Ballade, here I must say that Lear, just by playing straight,

produces a pleasingly sincere performance. It is the coda that fails

to clinch the argument. She can be heard negotiating all the notes very

ably but the difference between this and, say, Horowitz (just so as

not to say Rubinstein every time) is the difference between a creditable

performance and a scorching musical experience. And is it not conceivable

that Chopin himself, the "original Chopin", might have made

a scorching musical experience out of it ?

The B minor Mazurka is, above all, placid, except where

the triplets in the crossed-hands section seem to throw her and the

rhythm rocks every time. A comparison with Nina Milkina revealed a stronger

undertow of emotion but this is perhaps not one of Milkinaís finest

performances. Go to the first Rubinstein set (finely transferred on

Naxos) to hear a melodic line spun over the accompaniment with a vocal

freedom yet never betraying the mazurka rhythm. And you will never make

me believe that Chopin himself would not have better

recognised himself in this.

In the notes to the Polonaise-Fantaisie, "Those

Who" get severe reprimand. The "entirely new tonal effects",

which were "produced by a deep understanding of touch allied to

subtle pedalling techniques, transformed piano sound. (It is unfortunate

that Chopinís original pedal markings remain largely unknown)".

So "Those Who" have been mucking up Chopinís original pedal

marks. Which editions are wrong? Isnít a single one

of them right? As far as my humble ears can tell, Lear follows exactly

the markings in the Polish "Paderewski" Edition. If these

are Chopinís own, then I should have thought most pianists were aware

of them. Alfred Brendelís 1968 recording pedals the passage in exactly

the same way Ė and we all know that Brendel is not the man to use discredited

editions or to indulge in arbitrary interpretations of correct ones.

The comparison between these two performances is only

too revealing. Taken separately, Learís is a pleasing demonstration

of how a sincere belief in Chopinís text and a basic musicality can

allow the music to tell its own tale (except that here, too, triplets

seem to flurry her Ė she plays them too fast). Itís just that Brendel

goes farther up and farther in at every turn, with a just dialogue between

the hands in the B major section and an overall structural sweep that

makes one single, impassioned statement of a piece that can seem sectional.

(Brendel has turned rarely to Chopin but his one-off disc of Polonaises

is a fascinating document; it is currently available from Brilliant

Classics as part of a 6 CD box, 99351, and will be reviewed in due course).

The op. 17/4 mazurka is very successful. Given the

premises of "the original Chopin" it must be said that it

has about as many "personalised" rhythmic pointings (in the

first interlude) as anybody elseís; also, it is just as far as everybody

elseís from Chopinís metronome mark. This is a very swift marking and

would seem incompatible with the "Lento ma non troppo" tempo

indication. I donít advocate its observance, I merely point out that

this "original Chopin" ends up by raising doubts as to whether

the Chopin we know is so very "unoriginal". In this case Lear

is to be commended for an excellent performance.

Learís A flat Ballade is enjoyable, but Richterís recently

issued 1960 Carnegie Hall performance (RCA Red Seal 09026-63844-2 Ė

if you havenít got it then drop everything and run to the nearest shop)

is on another plane of existence. Even if you will look no further than

a correct realisation of the notes, then a speeding up of the "leggiero"

section (a mere few bars) is Richterís only textual sin. But for heavenís

sake, just listen to how every phrase at the beginning speaks,

how you can hear where each phrase is leading, and listen to

how he builds the work up to an overwhelming climax.

The B flat minor Scherzo shows Lear at her best, a

sensitive, technically secure performance that builds up well. I canít

honestly say I noticed anything musically or textually different from

the norm, in spite of the implied swipes at "Those Who" in

the notes. Referring to the opening bars we are told "It is crucial

.. that the irregular silences are measured as indicated". I concur,

and so, apparently, do many other interpreters, so I wonder who "Those

Who" donít count them out actually are. Well, a barís rest is lopped

off between bars 23 and 24 in this performance, though not at the corresponding

point later on. Maybe the extra barís rest (I have the Polish "Paderewski"

Edition in front of me) is one of those mistakes we have been making

all our lives, but then why not say so? We are also told in a footnote

that "Chopin was very particular with regard to the performance

of the opening triplet figure of this Scherzo .. and wrote: ĎIt must

be a question Ö a house of the deadí." "Those Who"

had got that wrong too, evidently, yet I can hear no basic difference

in character between Learís opening and Rubinsteinís. What I do hear

is that Rubinsteinís sound has a sharper profile, it speaks more.

This is the difference between great and lesser pianism, but Chopinís

text is respected in both cases. Lear also comments that "these

figures are usually snatched with an abrupt staccato Ďedgeí to the phrase

ends". Not by Rubinstein.

VOLUME THREE

I decided to try another tactic with the next disc.

Not to follow through with the score and bring out the comparisons but

just to sit back and let Lear play me a Chopin programme and see whether

the basic sense of communication is there. The trouble is I couldnít

keep it up. The opening of the F minor Ballade seemed so slow and spelt

out, rather mannered in its halting presentation, that I had to get

out the score and start again. The funny thing is, with the score it

seemed reasonable enough. So having got to the end I tried again without

the score. My conclusion is that, while Lear keeps large-scale tempo

changes to a minimum, her actual phrasing, and the rubato she uses to

point it, is very much on a bar-to-bar basis, with the result that what

looks like a fair representation of the score if you follow it

with the music open actually gets stuck over and over again, so that

the listener who just wants a musical experience never really gets engaged.

Itís all quite nice (but, given the "original Chopin" theme,

wouldnít one expect the stretto from bars 199-202 to be carried through

to the end, instead of being turned into a rallentando in bars 201-2,

and the staccato chords to be that, instead of the last one being held

an age with the pedal?). So there was nothing for it, out came Richter,

an under-identified performance from 1962-1966 on AS 343 and, truth

to tell, he indulges in no more tempo licence than Lear (bars 199-202

are virtually recomposed by means of the sustaining pedal but, as Iíve

just pointed out, Lear doesnít play what Chopin wrote here either).

What he achieves and she doesnít is a true cantabile to the themes,

a sublime simplicity in his phrasing, always guiding the ear to understand

the shape of the phrase, and he concludes with a controlled maelstrom

of sound which is beyond the ken of normal people like you and me and

Lear.

I actually did enjoy the op. 18 Waltz, feeling it had

an enjoyable swing to it, one or two clipped phrases apart. At the same

time, I felt it a rather effeminate grace I was being offered, more

suitable for certain movements from Schumannís Carnaval than

for the more fiery passion of Chopin, even at his most elegant. Still,

a nicely-turned account.

The B minor Scherzo is rather the case of Columbus

and the egg. Itís deftly managed, with a warmly-phrased middle section.

But this just doesnít go far enough when others offer a demonic brilliance

in the outer sections and poetic magic in the central lullaby.

In both the B major Nocturne and the C sharp minor

Polonaise I found once again that, while Lear keeps steady tempi in

the long term, in the short term her playing can be distractingly fidgety,

and with some more of her snatched triplets in the Polonaise, too. No,

I got limited enjoyment out of these.

Where the music is straightforwardly melodic, as in

the E flat Nocturne (and here we do get a textual novelty in the form

of a different cadenza noted down by Mikuli) and the early Polonaise,

she can be very pleasing (but couldnít we have had more sense of surprise

as the Polonaise introduces its Rossini quotation?). The F major Ballade

is a pleasant affair, too, though the placidity of the opening seems

closer to the world of Sterndale Bennett than

of Chopin. From the start of the Mazurka Nina Milkinaís performance

conveys a stronger profile, the music is going somewhere, with Milkina

developing a full head of passion as the music reaches its climax. Richter

may sometimes seem on the verge of flying out of control in the Scherzo,

but he conveys something. Iím afraid I have to record a sorry

case not unlike that of Helmuth Rillingís Bach, where a lifetimeís dedication

to the notes the composer wrote seems to me

not to have resulted in any larger

understanding of what the music says.

VOLUME FOUR

This disc brings with it a further manifesto in the

form of a free extra disc in which Angela Lear talks about playing Chopin,

first in general and then entering into some detail over the B flat

minor Sonata. On a number of occasions she goes to the piano and gives

us a few bars of a typical "Those Who" performance, adding

comments such as "Terrible!", "an amorphous mass of sound",

then following the demonstration with the same passage in what she believes

to be the correct manner. The problem is that, while Lear may not mean

to imply that the "terrible" performances are typical of the

likes of Rubinstein or Horowitz, some people might get that idea. This

is a point where I feel strongly that "Those Who" should have

been named. Could not Lear have illustrated her points with actual examples

from recordings by pianists who, however famous, she feels are imposing

their own egos on the composer? Alternatively the suspicion is that

"Those Who" are over-enthusiastic students or young hopefuls

just entering the concert-giving arena. But Lear does need to prove

that she is way above that level. It should be clear by now that, while

I donít think she plays the piano as well as Rubinstein or Horowitz,

I donít for a moment suggest she is less than professionally competent.

(And I havenít overlooked the fact that each programme, except the last,

was the result of a single dayís session, which means there was virtually

no time for faking. Most artists expect two or three days to record

a 70-minute programme). Speaking of the finale of this Sonata, she lets

us hear it in two ways, one an unholy mess, the other a good, very clear

performance. Still, the difference remains; that between an everyday

performance and a good one. Rubinstein lets us hear it in a third way.

He maintains the sotto voce marking as Lear does, he maintains

clarity as Lear does, but within this pianissimo sound he finds an infinite

variety of tone, he makes the phrases say something, and the final forte

pay-off is not just loud; it is stomach-wrenching.

However, the Sonata performance as a whole has many

strengths. Regarding the first movement, Lear does raise two important

points. Firstly, the main body of the work is doppio movimento,

exactly double the tempo of the slow introduction, while some performances

tear away at far more. Secondly, the climax of the development, as it

spills into the recapitulation, is hair-raisingly difficult and the

maximum tempo in which it can reasonably be done has to be the tempo

for the whole movement Ė there can be no putting on the brakes. It is

certainly interesting to hear this movement expounded rigorously and

steadily, and with the repeat. However, Rubinsteinís 1946 recording

is no less aware of these points (albeit repeatless) though the actual

tempo is faster. He seems to be virtually flagellating the piano at

the climax of the development, thrills and spills galore, but he manages

to hold the tempo and to engage the listener.

In the Scherzo it is Lear who makes little rhythmic

nudges here and there, compared with Rubinsteinís direct virility. The

lyrical sections of this movement, and the trio of the funeral march,

find him playing with peerless eloquence (and no distortion), and he

knows just as well as Lear does that the trio has to go at the same

tempo as the march itself. Learís left-hand-before-right is rather irritating

here.

Regarding the funeral march, Lear insists (probably

rightly) on the need to place the grace notes on the beat, and

protests that despite her efforts, a critic commented that she plays

them before the beat. The trouble is, while she certainly makes

the grace-note and the left-hand coincide, she rather nervously makes

both come in ahead of the beat, so it really does sound as if

the grace note is anticipating the beat. She and her critics seem to

be both right and wrong in equal measure.

As for the remainder of the programme, the A flat Impromptu

lacks real lightness of touch and has a doggedly heavy middle section,

but the next few pieces show Lear in altogether more favourable light.

The "Lento con gran espressione" has real poetry and a real

feeling for its harmonic movement. And, if in this rare piece I may

be thought more lenient because comparisons with the various 'Those

Who" are lacking, I found the F sharp Nocturne equally fine, warm

and flexible in just the right way. The E flat Waltz, another rare piece,

is nicely turned but the F sharp Impromptu is a shade perfunctory and,

strangely given her strong words about "Those Who" make unauthorised

tempo changes in Chopin, Lear rather forges ahead in the middle section.

She is to be commended for keeping the elaborate return to the opening

subject so clear, the pedal exactly as written, unfortunately she makes

it sound so dry.

The early Marche Funèbre is sensitively

done; this piece was new to me, so I cannot tell whether a certain monotony

is attributable to the composer or the performer. But in the op. 50

Mazurkas she brings over-inflected rhythms to bear on all three of them

and loses the cadence of the dance. The famous op. 53 Polonaise is competently

played but this is hardly enough when the likes of Rubinstein Ė for

one Ė can turn it into proudly patriotic statement without any need

for distortion.

VOLUME FIVE

Here, too, we get a companion disc. This starts off

with a talk by Professor Guy Jonson, Learís former teacher and now her

mentor, and for many years Head of Piano Studies at the Royal Academy

of Music. The gist of it is that heís seen it all and itís all awful

Ė except Lear. Then Lear herself tells us all about playing the Preludes.

Again, she has a lot of fun demonstrating "Those Who" performances,

but really, sheís flogging a dead horse. As early as no. 2 her examples

of how not to do it are so grotesquely unmusical that no professional

pianist on any level would be so ghastly. As a series of tips for students

the disc might have some use, but the implication is that Rubinstein

et al have never noticed these points. I must say, too, that

having spent very many hours trying to get the right syncopated effect

in no. 1, I rather resent being lectured on the matter as if Lear has

discovered it herself.

However, the disc itself is a pleasant surprise. Not,

maybe, the first few Preludes, for no. 1 is a little dry and the left

hand doggedly intrusive in no. 3. But I was captivated by no 10, its

Mazurka-hints integrated for once tempo-wise with the cascading quintuplets,

and by and large I found that thereafter Lear was at last arguing her

case with spontaneity and a real appreciation of the music. The Preludes

are perhaps the most difficult Chopin works to get right (though some

would say the Mazurkas) since the brevity of most of them means that

if the mood and touch of each one is not spot on from the beginning

itís too late to save the situation. Generally I found myself sufficiently

in thrall to set aside memories of other interpretations and simply

enjoy these.

The RAM acoustics (only the Preludes and Mazurkas were

recorded in the usual Bristol venue, and four years separate the sessions)

are more brilliant, but a touch clattery. Nevertheless I thought the

Valses had much vitality and Learís insistence on a steady waltz-tempo

is triumphantly vindicated. There is also much quiet poetry in the Nocturne

and the Barcarolle, not quite an impressionistic evocation à

la Lipatti, but joyously fluent all the same. The Mazurkas find the

natural rhythm which eluded the previous Mazurka performances.

So Volume Five deserves a place in our library of Chopin

discs for reference, and this raises the question of whether in her

own home, or in a public recital, she can achieve that easy dialogue

with the music which had previously largely eluded her in the studio?

Can it be that her many admirers who were instrumental in bringing this

series about had heard her play "in the flesh" with a flair

and communication which didnít come through at first to those who only

know her by the discs? The earlier volumes, as I made clear, suggested

something rather limited. Now Iím not quite so sure. If her next Volume

is on this level, I shall look forward to hearing it. And I wonder if

she is really doing the best she can for herself by sticking so rigidly

to Chopin. Surely she would make a good Brahms pianist, and how about

some clear-headed, un-neurotic Scriabin?

Christopher Howell