What have these two pieces in common? Both were written

in 1808. Both suffer – rightly or wrongly – from being pigeon-holed

as Division 2 Beethoven or neglected masterpieces, depending on your

point of view. Both are Piano Concertos which aren’t quite Piano Concertos,

involving as they do a solo violin and cello (in the case of the so-called

‘Triple Concerto’) or a chorus (and for a mere two minutes only, in

the piece we usually refer to as the ‘Choral Fantasy’). So neither piece

fits easily or comfortably (certainly not cheaply!) into a concert programme:

and they’ve probably been overlooked by concert planners and promoters

for precisely that reason.

In truth, they’re both (in their different ways) remarkable

pieces. Take the Triple Concerto. The discreet statement of the theme

in the cellos and basses which opens the first movement is extraordinary

(both as scoring and as thinking) for its time, and the tutti which

ensues is as exciting as anything in middle-period Beethoven. And of

all the transitory middle movements which typify so much Beethoven at

this time (think of the Fifth or Sixth Symphonies, the Rasumovsky Quartets,

the Fourth Piano Concerto, the Violin Concerto, the Waldstein and Appassionata

Piano Sonatas…) this is as beautiful, as mysterious and as intense as

any. But there are times in the first movement – and longer periods

in the rondo finale – where Beethoven loses his way and falls back on

rather empty convention.

It’s interesting that no one refers to Op 56 as a ‘Piano

Trio’ Concerto; and, in truth, it is no such thing. It really is a concerto

for three soloists who, although they need to work together as a team,

as often as not take turns to enjoy the limelight. This doesn’t suit

every front-rank soloist, of course. And it doesn’t benefit the structural

integrity of the concerto either, what with so much of the material

being repeated for the different solo instruments: the result is that

our interest can be divided rather than multiplied.

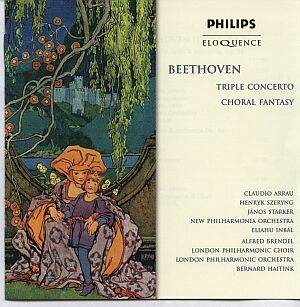

The Three Wise Men in this recording include Arrau

– an over-rated artist, I’ve always thought: will the editor sack me

for saying such a thing, I wonder? He plays well – solidly rather than

subtly. Szeryng is his usual excellent self, with secure intonation

and forthright articulation in the finale. Starker plays the slow movement

main theme (high up on his A-string) with glorious tone and the breathings

in and out you’d expect from a great singer, but his tone lower down

the instrument is less refined. Inbal accompanies loyally. The sum of

all this? A well-played performance which lets you hear what Beethoven

wrote, but doesn’t go all out to ‘sell’ the piece: there are better

characterised performances available in the catalogue, even at bargain

price. Tape hiss intrudes too.

The Choral Fantasy, I would argue, is definitely NOT

second-rate Beethoven: it deserves a wider hearing. It contains one

of Beethoven’s truly great and memorable themes, a prototype for the

choral finale of the Ninth Symphony. Indeed the whole work seems like

a dry run for later things. The closing pages sound like a sketch for

the closing scene of Fidelio; real Beethovenian ‘victory’ music. And

the element of improvisation and fantasy – embracing all manner of theme-variation,

recitative and counterpoint – are a foretaste of the Third Period (the

late Piano Sonatas and String Quartets) if ever there was one.

Both Brendel and Haitink are on magnificent form here.

Assertive and spontaneous, Beethoven would have been proud of them!

And the recording sounds splendid.

This disc affords a good opportunity to hear two fascinating

and rewarding pieces which can only deepen our understanding of this

always-complex and innovatory composer.

Peter J Lawson