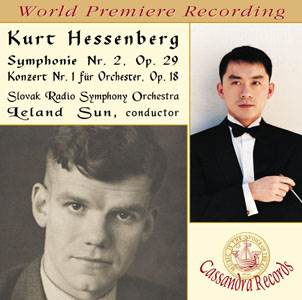

Kurt HESSENBERG (1908-1994)

Concerto No. 1 for Orchestra (Concerto Grosso) (1938)

Symphony No. 2 (1943)

Slovak Radio SO/Leland Sun

Slovak Radio SO/Leland Sun

rec March 2000, Concert Hall, Slovak Radio, Bratislava

CASSANDRA CR 201

[64.20]

CASSANDRA CR 201

[64.20]

AmazonUS

I am sure that it is quite possible to create great, enjoyable and/or

entertaining music under any régime. The creator may or may not be

in sympathy with the régime. What matters, surely, is the music. If

it is drab and uninspired that will show without any collateral knowledge

about the composer's sympathies or the régime under which that composer

lives.

Decca/London rewarding Entartete series of recordings (which seems to have

petered out) was produced bringing to light works by those declared by the

Nazis to be degenerate. I wonder how many composers who were Nazi submissives,

Nazi sympathisers or out-and-out Nazis produced music which, if we heard

it now without awareness of the dead composer's politics, would be hailed

as joyous, inspired or unjustly neglected.

The British composer Alan Bush was a frank communist. His communism brought

him into conflict with the BBC and his works undoubtedly suffered because

of his politics. The BBC virtually ignored him for years although amends

were made in the 1970s and 1980s. His music is worth exploring as is that

of similarly minded composers such as Frankel, Bernard Stevens and Christian

Darnton (though they were by no means a personally harmonious group). Bush's

hour long Busonian Piano Concerto (a natural you would have thought for CPO

to record) has a choral finale (you've guessed it - for men's voices) setting

'class struggle' words of Randall Swingler. Those words caused great controversy

at its premiere on the BBC during the 1930s - remember this was at the time

of the Spanish Civil War and of Britten's Ballad for Heroes. Then

work itself however has been revealed by last year's BBC Radio 3 broadcast

as a masterly piece - easily accessible and challenging at many levels. Bush's

music and that of his communist brethren is well worth resurrecting.

I wonder how long it will be before it will be thought

proper to re-examine, broadcast and record the works of composers who

were the presences, 'bright hopes' or elder-statesmen of Hitler's Germany.

People such as Pfitzner, Schoeck and Schmidt already have considerable

attention. What about the other composers active at that time? Can anyone

shed light on their work and assess it as music rather than as music

by people whose politics are utterly repugnant or who were supine to

a despicable régime built on and mobilising hatred?

I might make the same point about Imperial Japan and the Soviet Union. Somehow

the politics of dedicated communist composers are not seen as quite as

objectionable as those who pandered to, and outright supported, the Nazis.

How many Japanese composers are there who throve during the years of Japanese

imperialism but whose names are now forgotten or suppressed because of their

politics?

Perhaps this territory has already been well and truly explored but I would

still like to hear people's comments and to be reminded of any composers

eclipsed as a result of their Nazi sympathies rather than because of their

music. Surely it must always be tempting to say that a Nazi composer's music

is drivel, boring, without a shred of inspiration rather than to do the difficult

thing and listen past the man's politics and deeds (we do this for Wagner

and others) and through to the music itself. Is the music really irrevocably

infected by the politics, weakness, misconduct and worse of the composer?

Interesting to note Aaron Copland's stirring pastiche-Russian music for the

early 1940s film 'North Star' glorified the People's Struggle against the

Nazi invasion of the USSR (a politically attractive message in the USA during

the mid-1940s). Within a few years, so I understand, Ronald Reagan was condemning

Copland's music because of the composer's communist sympathies and indicating

that he would never work in Hollywood again!

Apologies for this ramble but I find this subject of discomfiting interest

and hope one day to read an exhaustive and even-handed study of the music

of neglected composers (and I do not mean just the big names) active in 1940s

Axis countries. Kurt Hessenberg was one of these. He was born (and died)

in Frankfurt. After studies in Leipzig (1927-31) he in 1933 became a teacher

at the Musikhochschule in Frankfurt. He stayed there and became a Professor

in 1953.

There may well have been extra-musical reasons why his music has not secured

more exposure although the mechanisms by which neglect and exposure are balanced

are surely far more subtle than a single indicator would suggest.

Virgil Thomson saw the score of the Second Symphony in Germany in 1945 and

wrote a laudatory appraisal of it in 1946. The Symphony is in four movements.

Its rapidly rocking preludial pianissimo has overtones of anguish and regret

mixed with Brucknerian resolve. A cousin to that rocking pattern reappears

at the beginning of the finale - also poco lento. A more determined

passage predominantly for the brass clears the air. This is not a work of

expansive late romanticism nor is there any hint of impressionism. There

is instead a simple strength to the writing like a clarified version of Franz

Schmidt's writings. The work exudes a dignified nobility associated with

its Bachian forebears. Leland Sun who proves himself an often inspired friend

to Hessenberg's curtained star makes much of the symphony. Hessenberg can

lumber and there is evidence of this in the symphony's finale. However what

stays with you about that movement is a Lutheran celebration rising up and

piercing trumpets crowning an hour of transient jubilation under louring

skies.

The symphony was premiered by Furtwängler and Berlin Philharmonic in

December 1944. German Radio made a recording. That recording has never been

found. We can hope that this CD will prompt radio stations and archives to

renew their search.

The Konzert No. 1 is even more assertively Bachian with its skirls and fugal

character. I am not at all sure that it could be fairly labelled academic.

The music has some of the fibre and sinew of one of Stokowski's Bach syntheses

but shorn of the extremes of the chromatic palette. Both in the symphony

and the Konzert I thought often of Rubbra. Hessenberg's creativity has a

similarly unglamorous character. It intrigues me that the Konzert and the

symphony are broadly contemporaneous with Rubbra's Third and Fourth Symphonies.

The discords of the music are soft, with scolding greys and sullen browns

rising along dignified Bachian contours to a stern elation snatched away

by emotional ambivalence. The chuckling woodwind of the Konzert is a heavier

treaded version of Dumbarton Oaks. Hessenberg scorns grand romantic

afflatus and instead picks up the reins of neo-classicism and sometimes embraces

a swarthy Brahmsianism. In the finale of the Konzert Hessenberg seems to

reach across to the symphonic Rubbra - peak to peak - his Concerto to Rubbra's

Fourth Symphony.

Apart from Hessenberg's Lieder eines Lumpen, op. 51, sung by tenor Christian

Elsner (Charles Spencer, piano) on the Ars Musici label (also in association

with BMG/RCA) there are, to the best of my knowledge, no other Hessenberg

CDs. However a number of recordings circulate on the tape and CDR underground

including the Two Piano Concerto, the Cello Concerto, the Sinfonietta da

Camera and the Piano Concerto.

A most intriguing disc, thoroughly well documented. A real credit to Cassandra's

sense of adventure. Long may such ventures continue. We must have high hopes

that the company will engage with its audience and strike out in further

esoteric directions.

Rob Barnett

This review of Kurt Hessenberg's music involves a lot more than just listening

to the CD. Let me explain. I must first of all confess that I am no 'Hessenberg'

expert; in fact before the CD arrived in the post I had never heard of him.

Although the name sounded a touch familiar, I am sure I was getting confused

with Heinrich Herzogenburg, the Austrian composer and conductor from the

early nineteenth century. (Incidentally his music is being rediscovered as

well) A glance at my copy of Eric Blom revealed nothing; no entry. Even the

new Grove has very little to say on this prolific composer. Fortunately all

was not lost. 'Cassandra,' the CD producer has done an excellent job in helping

the neophyte out. The sleeve notes are a model production; if only all CD

companies provided such comprehensive details, the listener would be so much

more enlightened.

There is, besides the usual notes on the two programmed works (a bit more

detail of the actual works themselves, perhaps?), the players and the conductor,

an essay, and I mean an essay, entitled 'Pantheon of Greatness or a Footnote.'

There is also an introduction by the composer's son, and the copy of a letter

from Furtwängler to Hessenberg. But that is not all. A quick surf on

the Internet revealed two relevant sites; both produced by the record publisher.

The first is a list of works and the other is an interesting autobiography

of the man himself. However, the whole review really revolves around the

title of the essay quoted above; was Hessenberg a footnote, or did he have

genius?

Let's dispose of the aesthetic bits. The CD is beautifully produced. I cannot

fault the playing, the quality of the sound, the sleeve design or the programme

notes. The conductor, Leland Sun, has contributed to the Hessenberg scholarship,

as well as giving us a first class performance. The programme is excellent

too, giving, in just over the hour, two of the composer's 'best known' works.

To my mind it is a fine example of what a CD should be. Anything I may say

about the music or the composer does not detract from the quality of this

production. It is really a must for all enthusiasts of 20th century

music.

Who was Kurt Hessenberg? Well, the answer for a review has to be fairly succinct.

Besides the autobiography is easily available on line:-

The composer was born in Frankfurt on 17th August 1908. He studied

music at Leipzig from 1927 until 1933. He had a relatively straightforward

life insomuch as he was appointed to teach music at the Musikhochschule in

his home city, in 1933. He remained there till he retired. Hessenberg died

in 1994.

It is not until we study the catalogue of his works that we get some sense

of this composer's achievement - at least on scale. Most of the musical genres

are represented somewhere in the 135 'opus' numbers. There is a massive amount

of chamber music to explore. Eight string quartets, two string trios, a piano

quartet and lots of instrumental sonatas. The list is almost endless. He

wrote one 'comic' opera called 'The Striped Guest.' There is a substantial

collection of choral music for both accompanied and unaccompanied voices.

Orchestral music is represented by four symphonies, the earliest from 1936

and the latest being published in 1980. There are concerti for piano, bassoon,

'cello and violin. Many suites and concertante music and variations make

up this fascinating catalogue.

What were Hessenberg's influences and background? His study at Leipzig in

the late twenties and early thirties was done against a background of stunning

musical activity. The composer heard Karl Straube and the St Thomas Choir;

he listened to the Gewandhaus Orchestra with their conductor Bruno Walter.

He heard the latest works by men such as Paul Hindemith, Zoltan Kodaly and

Igor Stravinsky. The political troubles of the era had a deep impression

on the composer.

The two works, which we have to consider, are the Concerto for Orchestra

No. 1 of 1938 and the Symphony No. 2 of 1943. This is really all

the data we have to make up our minds about this prolific yet relatively

unknown composer.

The Concerto started life as a Concerto Grosso. But the composer

felt that the scale of the work was considerably larger than most of the

works which go by this name. It was renamed in time for the first performance

at the International Music Festival in Baden-Baden in 1939. According to

the programme notes this work became the most performed of Hessenberg's 'opera'.

It attracted critical acclaim. It was taken up by many conductors including

Furtwängler and Solti. The first thing we notice is that it does not

seem to be influenced by serialism or other avant garde techniques which

were gradually becoming available to composers just before the Second World

War. That is not to deny that he was very free with his tonalities. What

strikes one immediately is the neo-baroque feel to this music. That of course

is hardly surprising, for Handel wrote 12 concerti grossi. But this is not

Handel updated for the 1930s; it is not a parody of baroque contrapuntal

practices. It is an extremely competent exercise in writing for a large

orchestra. Hessenberg has taken his great love of the Baroque era and has

fused this with an understanding of the contemporary musical colour of his

own era. It is not for nothing that the names of Hindemith and Bartók

are quoted as being influential. The composer makes this connection in his

autobiography. It is a work that is full of high spirits; quite a pleasure

to listen to. It is quite a cerebral work; there are not big tunes of 'romantic'

harmonies, but as an exercise in neo-classical composition it is almost without

peer.

The Symphony No. 2 was completed in 1943. After the performance

of the Concerto for Orchestra, Furtwängler was so impressed with

Kurt Hessenberg that he became a kind of mentor to the composer. The conductor

was seriously impressed by the new score and expressed a desire to give the

work its first performance and to present it whenever possible. Of course,

at this time, the war caused many problems for musicians, but the symphony

was premiered in Berlin at the 'Admiralsplast.' The Philharmonie had been

destroyed. The new symphony was massive - lasting some 42 minutes; it is

in four movements. The composer himself is justifiably proud of this work

and states that it is very much in the Austro-Germanic tradition of Brahms

and Bruckner.

It is unfair to try to pick bits of this great work out and claim that it

sounds like this or that other composer. Hessenberg was perfectly capable

of absorbing music that was around him and producing a sound that was distinctly

his. Although everything about this work says 'neo-classical' it does have

a certain romantic quality to it. Every so often a 'tune' sets out on a journey

which has all the makings of a quite a 'pop' feel to it. However the composer

uses it and then just quietly folds it away. He has again avoided falling

prey to contemporary fashion or gimmicks. There are great climaxes, which

apart for the extended tonality could have come from the pen of a Beethoven

or a Brahms. He is a master of orchestration and especially in his writing

for brass. He makes use of a variety of percussion instruments, but does

not use them simply because they are there! Subtlety would be the best

description of his instrumentation.

Just looking at the symphony in a little more detail I will briefly consider

the 2nd & 3rd movements.

The slow movement is a fine example of the composer's skill - opening with

an intense unison; it soon sinks into a quiet almost Copland-like reverie.

Use is made of soft dissonances and some polytonality lends a definite

bittersweet feel to much of the scoring. There is a big build up toward the

end of the movement, which then collapses a number of times before a somewhat

unusual ending for a slow movement.

The scherzo is superb. It is full of energy. From the first note we feel

that here is a strong and vital movement. Loud and quite brash it nevertheless

manages to have its moments of repose. There is a marching theme here, with

an insistent side drum. Then there is a much more relaxed 'trio' section.

However the uneasy brass is never far from the surface. Bass clarinets give

some eerie sounds toward the end of this movement. Eventually the 'relaxed'

tune tries to return - with somewhat of a swing to it. But burbling woodwind

and drums soon knock it out of the way. The movement ends with the same energy

as it began.

The last movement is long and complex - divided into four sections. There

are all kinds of music in this. Martial even. It is a superb finish to this

fine example of the symphonist's art.

There is no programme to this symphony. It is pure, absolute music and it

is none the worse for that. We can listen to it for the sheer pleasure of

the sounds and not bother ourselves whether the composer was trying to make

a political or personal statement.

So what are we to make of all this? I have only made pointers to this music

rather than attempting a detailed analysis. Such an analysis will require

much more background information and most certainly the availability of the

scores. However, I believe that this work will and must be done live.

I have no doubt that we are in the presence of a very fine composer. Hessenberg

is unjustly denied his true reputation. If we care to extrapolate his entire

'opera' from these two works, if we assume a degree of consistency, then

what we have here is a major achievement. Hessenberg can take his place in

the pantheon of European and world composers with pride. He is a big hitter.

We need more of his music. Often critics make this cry about an obscure composer,

and to a certain extent it is whistling in the dark. However, I truly believe

that Kurt Hessenberg's time will come. I have no doubt that he is better

known in his homeland - but I imagine that even there he is less appreciated

than he deserves.

To use the word genius is always dangerous. I would not wish to ascribe

the epithet to anyone, especially after hearing only a couple of pieces.

However the sleeve notes propose the question 'Pantheon of Greatness or a

Footnote.' Now the unfortunate truth is that he has become a 'footnote' by

default. It is time he was studied and listened to and raised to the stature

he deserves.

A truly great composer with two fine works. They should be on the shelves

of all who enjoy symphonies in the lineage of Brahms and Bruckner. I hope

that Cassandra Records will continue to produce more works from Hessenberg's

catalogue.

John France

This is a fine CD. Two works by a forgotten composer who well deserves to

be rediscovered. It is not too much of an exaggeration to say that Kurt

Hessenberg was probably a genius. A must for all lovers of the best in

'neo-classicism.'

NOTE - information courtesy of our very good friend Eric Schissel

There are other HESSENBERG recordings:-

CALIG 50908

has among other things Hessenberg's Fantasia Ich ruf zu dir, Herr Jesu Christ,

op. 115

played by Edgar Krapp on the organ of the Frankfurter Paulskirche.

EBS 2-CD set Dresdner Kreuzchor, another set on DG called "Musica Divina"

with the same ensemble (which also has some Draeseke) on which the Hessenberg

item is O Herr mache mich zum Werkzeug deines Friedens, his op. 37 no. 1

One Hessenberg item on a piano recital on Fermate by Emmy Best-Reintges (Fermate

doesn't presently have a website)

Motette CD 60241 with works by Couperin, Bach, Litaize and Hessenberg (organ

taken by Andreas Boltz and Wolfgang Kleber; Kleber plays the Hessenberg work,

Choralpartita "Von Gott will ich nicht lassen", and some of the others)

Motette CD 11261 Kleber plays the trio sonata for organ op. 56, the prelude

and fugue op. 63 #1, the fantasies opp. 66 & 115, the toccata op. 128

and the passacaglia op. 127.

A search on Hessenberg also revealed what seems to be a music-cassette his

cantata Der Struwwelpeter Op 49.

Eric has seen the first 4 quartets in score, the sonatas for cello and (iirc)

viola, the 2nd symphony, and this and that else. (The cello sonata and 4th

quartet seemed especially promising)

Website:

http://www.thiasos.de/Komp/hessenbergd.html

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

NOTE AND ORDERING DETAILS

Cassandra Records is a brand new label, and this the initial entry in their

catalogue. The company is dedicated to bringing other neglected repertoire

into the public consciousness, but at a conservative rate of only one or

two releases per year.

Their postal address is as follows:

Cassandra Records

5701 Windcroft Drive

Huntington Beach

California 92649

U.S.A.

The Hessenberg disc can be ordered from the above address at the price of

$16 per copy. Postage and handling to within the United States is $2.00 by

first class mail or $4.00 by priority mail for the first copy. (Appropriate

sales tax would apply to California residents only.) To the U.K. that would

be $4.50 by economy (surface) mail for up to three copies, or $5.50 by air

mail for the first copy. Cassandra can accept payment only in U.S. currency,

by check that draws from an U.S. financial institution or by International

money order, made payable to "Cassandra Records". The disc is available also

through a few select independent retail, mail-order, and online merchants,

as listed on Cassandra Records's Web site.

The official entry point for their Web site is:

www.CassandraRecords.com

* Hessenberg's other recordings, if in print, are difficult to find. However,

the German CD retail site www.jpc.de offers

several