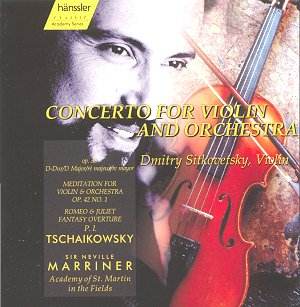

TCHAIKOVSKY

Violin Concerto in D, op.35

Meditation, op.42/1

Romeo and Juliet: Fantasy-Overture

Dmitry Sitkovetsky (violin)

Dmitry Sitkovetsky (violin)

Academy of St. Martin in the Fields/Sir Neville Marriner

Hänssler CD 98.346

[68'08"]

Hänssler CD 98.346

[68'08"]

Crotchet

Amazon

UK

A companion to the same artists' Sibelius

disc, in which the violin concerto (plus, in this case, the

Meditation which was its original second movement) is coupled with

Shakespeare-inspired orchestral music. Having questioned the balance between

soloist and orchestra in the Sibelius, I am happy to report that the present

recording is excellent in every respect.

After a curiously inconsequential opening flourish Sitkovetsky provides much

fine playing. Unfortunately this performance shares with the Sibelius a tendency

on the soloist's part to get slower at the least opportunity, and here the

damage is not limited to the first movement since the finale, too, is steered

into the doldrums whenever a lyrical theme comes into sight. The slow movement

is less affected and the Meditation is a complete success.

The orchestra has a strictly accompanying role but it has to be said that,

when it has something of its own to do, Sir Neville does it rather blandly.

The wind-playing lacks pungency of timbre and the ear expects the open fifths

that introduce the finale's second subject to rasp more. Marriner's strengths

in Tchaikovsky lie in nicely sprung balletic rhythms (there are some very

winning moments in the Meditation where the violin rides over chugging

triplets) and a certain elegance of phrasing. It need hardly be said that

this is not enough for Romeo and Juliet and one wonders if he is

deliberately setting out to expunge the work of its extra-musical Shakespearian

connections. For much of the time Tchaikovsky's own passion carries the day

but there are moments which almost undermined my faith in the piece. The

alternating string and wind chords before the fight breaks out have no meaning

if not animated by some sort of imaginative participation on the conductor's

part and the lead into the first appearance of the love theme emerges as

mere throat-clearing.

As a comparison I listened to Boult in Romeo (a World Record Club

original which turns up in EMI compilations from time to time), not because

Boult was supreme in Tchaikovsky (for a full baring of the composer's neuroses

one would go to the likes of Mravinsky or Markevich) but because his concern

for structural logic and dislike of rhetoric might have been expected to

lead him in the same direction as Marriner. But not so; Boult was too great

a musician not to grasp the fundamental point that without an element of

self-dramatisation this sort of music does not get off the ground. There

is tension right from the start, the love-theme has a recognisably Tchaikovskian

yearning and the performance swirls and surges to an overwhelming climax

that leaves the listener in no doubt that this is one of the most passionate

and tragic love stories ever told. I wish I could find some compensating

advantages in Marriner's approach but I have to conclude that it is basically

misconceived.

In short, Sitkovetsky's admirers will be pleased to hear him in the two concerted

pieces and we may hope that he will learn to express his love of the music

less indulgently in the years to come, but Romeo really will not do.

Christopher Howell