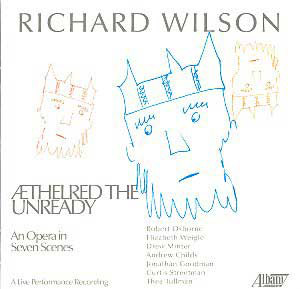

Æthelred the Second was King of England from

978 until 1016. Emma, his wife, was the sister of Richard II, Duke of

Normandy. He acquired the epithet "the Unrede" (i.e. "the

ill-counselled") which was later corrupted to "the Unready".

He was cursed at his baptism by Dunstan, the Archbishop of Canterbury,

for defiling the font. Dunstan’s curse, as well as other facts, is recorded

in the chronicles of William of Malmesbury. So much for history, for

Richard Wilson’s own libretto for his chamber opera, though drawing

on the chronicles of William of Malmesbury, tells another story.

Emma is dismayed by her husband’s "abject passivity",

unworthy of a Saxon king. So, on the occasion of Clio’s upcoming tribunal,

she wants to boost her husband’s reputation in spite of Æthelred’s

reticence. Indeed, Clio has never heard of Æthelred and plans

to asks William about him, but the latter embarks on one of his favourite

digressions about Saxon kings, so that Clio does not remember Æthelred’s

name. Emma consults the Publicist who encourages her to meet William

and suggests that Æthelred seeks advice from the Hypnotist. Emma

meets the historian who again gets carried away on the subject of Saxon

kings, and she obtains no assistance whatsoever. On the other hand,

the Hypnotist provides Æthelred with three mystic words (artichoke,

synecdoche and tabernacle) which, when put together in one telling sentence,

will give him courage to face Clio’s tribunal. But he must avoid the

forbidden word : chickenfeed! The interview with Clio begins in the

best possible way. The spell works! But Æthelred, perturbed by

Clio’s assistant, utters the forbidden word, and the spell is broken.

Clio dismisses him as a fraud. Emma scorns him for failing. The Publicist

suggests another strategy whereas the Hypnotist has Æthelred asleep

again. During his sleep, Emma, Clio, William and the Publicist sing

warnings against sloth and indolence while advocating bold and bloody

actions. Æthelred wakes up and decides to get rid of them all

so that he may be left in peace. (The above unashamedly draws on the

composer’s synopsis printed in the insert notes.)

Wilson’s chamber opera is a quite entertaining work

that does not aim at plumbing any great depths. The music is appropriately

light-hearted and lively throughout, deftly and lightly scored thus

allowing the words to come through clearly, an essential point in such

a work in which much actually happens, as it were, in the words rather

than in the dramatic action. Originally the work was scored for a middle-sized

orchestra; but the scoring was drastically reduced to an ensemble of

six players (as recorded here). From a purely practical point of view,

this should enable smaller opera companies to stage the work, but I

suspect that some of the orchestral variety is missing in the ensemble

version. Though definitely very amusing, the opera fails to succeed

and convince completely because it lacks set pieces or arias, although

the libretto actually offers many such opportunities. The only moment

resembling some sort of aria is in the last scene when Æthelred

sings a folk-like love song, whereas the only ensemble also occurs near

the end of the opera. I cannot but feel that some fine opportunities

have been missed in this otherwise attractive and entertaining work.

It should be quite effective when staged, but nevertheless bears "blind

listening" well.

The live recording of this semi-staged performance

is remarkably clean with very little extraneous noises, except for the

audience’s enjoyment of the more amusing moments and appreciation of

the work after the performance. The present performance conducted by

the composer is excellent, and so are the singers and the players.

Hubert Culot