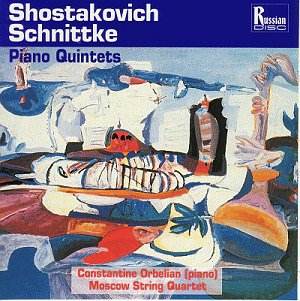

These two pieces make such excellent bedfellows that

I’m surprised the coupling is not more common, though as I write this,

Naxos have just announced their own recording of the same pairing. The

Shostakovich seems to me an unfairly neglected work, considering its

instant popularity after the 1940 premiere (the composer with the Beethoven

Quartet). It was written in the wake of the Sixth Symphony, and is his

last major pre-war piece. It encompasses many of the traits for which

the composer is famous; there are the intense, neo-Bachian first and

second movements, a playful, heavily ironic scherzo, a pensive, soulful

intermezzo, and a finale where probing questions lurk beneath a surface

veneer of jovial high spirits.

The artists on this disc seem to understand most of

these characteristics, and that elusive balance between seriousness

and parody is well caught. The slowly unfolding fugal second movement

is particularly impressive, and I like their lightness of touch in the

deliciously witty scherzo, where sarcasm and a clumsy, almost brutal

rusticity go hand in hand. The piano playing throughout is impressive,

and some occasional sour intonation from the string players is hardly

off-putting – indeed, one can argue that the sheer rawness of some of

this music is far better conveyed here than with an immaculate, plushly

virtuosic reading.

The Schnittke also receives an excellent performance,

and is, in many ways, a finer work than the Shostakovich. The older

composer was clearly an influence, but the real inspiration was the

death of Schnittke’s mother, and this produced a directness of utterance

that is truly memorable. It is certainly true of Schnittke (and other

composers) that some of his best work is in the chamber medium, and

this quintet is acknowledged as a key piece. The almost child-like naivety

of the opening immediately captures the attention, and this theme is

explored with astonishing skill and variety of texture from such modest

forces. Schnittke constantly teases the ear with his inventive sonorities;

try 3.17 into the pensive andante, where eerie string clusters form

a backdrop to a simple piano unison, hypnotically repeated. One can

sense the torment and anguish that is finding a musical voice here,

and when the tortured sounds finally give way to a finale of almost

unbelievable simplicity, one feels a calm resignation, a letting go,

that is deeply moving. This is a magnificent work, and this performance

certainly does it justice. I can imagine quartet playing of greater

variety and depth of tone, but there is a real Russian ‘edge’ that has

its own rewards, and the playing of Constantine Orbelian is little short

of inspired.

The recording is obviously coming to us from a large

empty space, but with fairly close microphone placing, no intimacy is

lost, and the balance between instruments is good. Notes are reasonable,

though there are typos and wrong timings. But all in all, this is a

release well worth investigating.

Tony Haywood