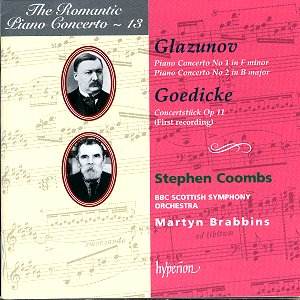

Stephen Coombs has made Glazunov's piano music a central

part of his repertoire. His recorded performances of the complete works

for solo piano drew high praise. So too are these performances of the

two concertos notable achievements.

Glazunov came to the concerto relatively late.

A prolific composer from his teenage years, he had already written the

symphonies which dominate his creative output, as well as the magnificent

ballet scores Raymonda and The Seasons, before he turned

to these piano concertos. The Violin Concerto dates from the mid-1900s,

so the same point applies to that piece too, if not quite so strongly.

These ideas are not without importance, since three

of Rachmaninov's piano concertos had been written by the time of Glazunov's

Concerto No. 1. Despite the boldly original form, the music remains

in the shadow of Rachmaninov's style, though, to be fair, Glazunov does

idiomatically share the richly romantic outlook of the post-Tchaikovsky

generation of Russian composers (he was eight years older than Rachmaninov).

His orchestral writing is as opulent and imaginative as we would expect,

and the piano part balances imaginatively with it. Anyone who enjoys

this kind of musical indulgence - and most of us do - will enjoy Glazunov's

concertos.

The first movement has a splendid sweep, with a gloriously

lyrical second theme which receives the full treatment. All praise,

therefore, to the Hyperion recording for conveying this so indulgently.

The second and final movement is an extended theme and variations, using

titles such as 'eroica', 'quasi una fantasia' and 'mazurka'. It is as

if Glazunov was prompting himself to compose the music from a preconceived

plan. But the concerto does sound a good deal more spontaneous than

this, and both Coombs and Brabbins respond to its shadings, the ebb

and flow of tension and relaxation.

There is a tendency in the First Concerto to emphasise

the romantic expression and the lyrical flow, perhaps at the expense

of displaying the technical display which must remain a priority in

a romantic piano concerto. These thoughts are paramount also in the

Second Concerto, whose highlight is a central Andante of thoughtful

construction and deeply felt emotion; it is therefore very Russian.

The opulent recorded sound emphasises these characteristics, and may

be responsible to some extent for the (relative) failure of the more

lively outer movements to provide the kind of excitement which the indulgence

of romantic virtuosity might demand. One wonders whether a little more

drive and power might have brought dividends.

There are no such worries in the shorter concluding

item, the Conzertstück by Alexander Goedicke. Despite living

on to 1957, he composed this piece as early as 1900, a decade before

Glazunov wrote his piano concertos. Goedicke, born in Moscow in 1877,

was the cousin of Nikolai Medtner, in whose shadow posterity has left

him. But he was a musical talent in his own right, who from 1909 served

as professor of piano at the Moscow Conservatoire.

According to Francis Pott's thorough and well written

insert notes, Goedicke's creative efforts were most successful in the

earlier part of his career, and the Conzertstück is therefore a

typical example. It is a somewhat diffuse piece, whose structure relies

considerably on the motto theme with which it opens. The piano writing

tends to be complex and decorative, and Stephen Coombs responds to

it enthusiastically and directly, playing with much brilliance. Although

this is in no sense a major work, it is most engaging, and its addition

to the catalogue in this, its only recording, is therefore welcome.

Terry Barfoot