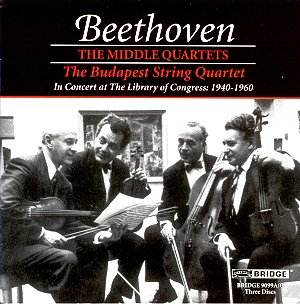

Admirers of the Budapest String Quartet have recently

had cause to celebrate their good fortune. A profusion of recordings,

archive and re-releases, have restored or added to a discography already

well documented. Bridge have released two three CD sets devoted to recitals

given by the Quartet at the Library of Congress during their residence

there which ran from 1940-62. Remastering has been judiciously applied,

albeit the rather boxy acoustic of the Coolidge Auditorium must have

proved initially somewhat unsympathetic.

It’s difficult to underestimate the ascent of the Budapest

Quartet in American musical life or their perceived supremacy over many

years. From 1930 until 1962 they performed approaching sixty cycles

of the Beethoven Quartets and made three studio recordings of them –

one on 78, one on mono in 1952 and one on stereo LPs in 1959. For The

Library of Congress they performed the cycle four times, from which

come the recordings enshrined in these discs. The bulk come from the

early to mid 1940s – though one of their most searching interpretations

Op 59 No 2, is heard here in a performance from April 1960, a year or

so after they made their last commercial recording of the cycle. With

so few sound problems – a small patch due to a damaged master is noted

in the Presto of Op 74 - we can concentrate more fully on the extra

quality of energy and immediacy generated by these live performances

and admire the many qualities that made the Budapest so eventful a foursome

– their sense of momentum, instrumental finesse, cohesive tonal palette

which tended to the rarefied, a certain objective, rather analytical

approach, though not one devoid of depth or powerful and lyrical currents

of feeling. The level of musicianship is exceptionally high here, intonation

excellent, and ensemble secure.

The traversal of Op 59 No 1 is of real stature, confident

and lively playing by Joseph Roismann, the leader, with an ebullient

Allegretto and powerful intensity and consonant sense of arching line

in the Adagio. The second CD features the only performance here with

Edgar Ortenberg as second violin. He replaced Alexander Schneider when

the latter resigned to join other chamber groups. Ortenberg was a fine

player with a notable recording of Hindemith’s Third Violin Sonata to

his credit but is generally held to be a "cooler" player than

the more extrovert Schneider. This performance was recorded over two

days, 6th and 7th March 1946 the sleeve note writer,

Harris Goldsmith, avers that this is a "bolder and less silken"

reading than the quartet’s other recordings – but to my ears though

I admire the narrative grip of the first movement, the questing nobility

of the Andante and the strongly declamatory tone they can impart I still

found parts of the Minuetto intolerably manicured and glib. Op 59 No

2 however – in striking and immediate 1960 sound – was a Budapest speciality

and first recorded by them in 1935, at a time when Istvan Ipolyi, the

sole surviving Hungarian member, was still with them. The recording

preserved here is from the last of the four Library of Congress Beethoven

cycles and convincingly demonstrates their consistently inspired way

with this music. The passionate and engaged performance is very slightly

tighter and tauter than the commercial recording of a year earlier but

with little loss of lyrical momentum. The Adagio from that 1959 cycle

is one of the most moving that I know and whilst this live performance

doesn’t quite match it, the Budapest have an extraordinary powerful

way with it.

Op 74 is a forceful and not at all avuncular affair

with its primus inter pares role for Roismann – who acquits himself

with distinction in an interpretation about which I am at best ambivalent.

It seems unyielding to me. Harris Goldsmith is an excellent guide through

the various recorded cycles, comparing and contrasting performance practice

and subtleties of interpretation. He is perhaps – understandably – overgenerous

to the quartet with regard to the 1940 Op 95 – in their subsequent December

1941 reading they were somewhat broader and less discursive, less prone

to impose manifold abrasions and disjunctions on the line – but this

was never one of their most winning interpretations.

In addition to the performances CD 1 boasts a six minute

spiced interview with Alexander Schneider from the late 1980s – charismatic

as ever. Altogether this is an invaluable addition to the important

discography of the Budapest Quartet in excellent sound, splendid documentation

and full of concentrated wisdom.

Jonathan Woolf