Both concertos date from around 1830, and how amazingly

unlike Beethovenís Emperor they are. Piano writing was advancing

by leaps and bounds, diversifying in all directions as the instrument

itself developed in terms of its technology. Chopinís two concertos,

together with the Andante Spianato and Grande Polonaise, have

a reputation for shallow sparkle and turgid orchestration but both descriptions

are wholly inappropriate, especially when they are in the hands of sensitive,

informed performers. They have an endless stream of inventive melody,

lyric emotion and lithe energy, while such devices as col legno

(using the wooden part of the bow to strike the violinís strings, rather

than the hair, to draw the sound) must represent, along with Berlioz

in his Symphonie fantastique from exactly this same period of

1830, an early departure from the conventional approach. Then thereís

the Polish dance (the Krakowiak in the finale of the first concerto)

to catch the spirit and rhythm of Chopinís homeland, which he left for

good at this time.

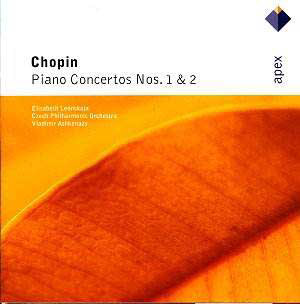

I recently reviewed Martino Tirimoís 1994 recording

on REGIS of the same pair of concertos, which came in at something just

over four minutes longer overall. Only in the Larghetto of the second

concerto, reputedly dedicated to Chopinís secret love, Konstancia Gradowska,

is Tirimo slower than Leonskaya, so thereís something of a different

approach here in terms of tempos as there is with the conductorís contribution.

It must be somewhat intimidating to have someone of the pianistic calibre

of Ashkenazy on the podium while you play what is very much his repertoire,

but Leonskaya stamps her own mark on this live recording in a no-beating-about-the-bush

approach, yet, despite the noted faster timings, there is no sense of

breathlessness in her playing, on the contrary her phrasing breathes

and expands to accommodate a stylish feel for rubato in shaping those

warm melodies. The orchestral solos (horn and bassoon particularly)

are too remote from the back of the stage in Pragueís Rudolfinum, and

the string sound has a woolliness in places, but when Ashkenazy lets

them off the leash, the Czech Philharmonic make the most of their moments.

A recording to savour, but listen to Tirimo on REGIS before choosing.

Christopher Fifield