Petrassi was born at Zagarolo not far from Rome. For

his seventieth birthday Zagarolo staged a torchlight parade and a reception

for its famous son. Under the influence of Casella he became an enthusiast

for neo-classicism with a proclivity for driving rhythmic material.

It was not that much later that this blend was further infused with

12-tone techniques pragmatically applied. On Petrassi's visit to the

USA in 1955 and 1956 he took considerable time exploring and rejoicing

in the avant-garde styles of Jackson Pollock and Ben Shahn (William

Schuman wrote an orchestral piece eulogising Shahn - In Praise of

Shahn).

This is another significant and perhaps unglamorous

set. It is significant because it makes available, for the first time,

recordings initially issued on Italia LPs in the late 1970s. I remember

seeing them in a boxed set in the crammed basement of the Music Discount

Centre on Dean Street in London circa 1980. Unglamorous - because Petrassi's

styles developed out of neo-classicism into the challenging and dodecaphonic.

The First Concerto is Stravinskian with burly

rhythmic energy - blunt and coarse and undeniably exciting. The playing

is not blessedly clean. In the middle movement we are aware of the noisy

ghost of the Venetian Gabrielis. The singing violin melody could be

less thin lipped and more fruitily lustrous. The brass role is reminiscent

of the climactic fanfaring release of Rubbra's Eleventh Symphony. The

Adagio is well worth hearing. This is full hearted neo-classicism.

The contrast between the three movement First and the

single span of the Second Concerto has its parallels with the

differences when comparing the William Alwyn First and Second Symphonies.

There is a tickling anxious undertow and the strings while better groomed

than in the first concerto remain astringent. Petrassi deals in Bergian

half-lights and sepia tones which flit and melt in surreal motion. However

unlike Alwyn in my comparison Petrassi has learnt from Ravel in his

use of pismire fanfares and insect tumult. There are even some Sibelian

splinters along the way.

The Third Concerto rattles and echoes with petulant

blasts and shrieks - rather like an angry version of Nielsen's Sixth

Symphony. This work was premiered in July 1953 at Aix-en-Provence under

Hans Rosbaud. A non-formulaic dodecaphonist is clearly at work here

and to that extent he might well be thought of as a brother to his contemporary,

Benjamin Frankel, who had a similar taste for Bergian lyric material.

Dance is also an interest as at track 5 (CD2) 11.18. Petrassi used Schoenbergian

method freely.

The Fourth Concerto is for strings alone. As

they were in the Third Concerto the Philharmonia Hungarica seem utterly

at ease in this music and their high violin tone is sublimely silky.

They explore ionospheric regions in an atmosphere of saturated beauty

that is truly gripping - try track 1 4.20. This music is like a blend

of Sibelius's string writing from the Fourth Symphony with Hartmann

and Pettersson - definitely the highlight of the set.

The Koussevitsky Music Foundation commissioned the

Fifth Concerto for the 75th anniversary of the Boston Symphony.

The Bostonians premiered it on 2 December 1955. There is creepy string

writing sounding like a dodecaphonic version of the haunted midnight

nostalgia of Vaughan Williams' A London Symphony or the march

interjections from Nielsen 5. The work uses a theme from his Coro

di Morti, a dramatic madrigal dating from 1941 premiered in Venice

in 1941 and which then received multiple performances in several US

universities in the late 1940s and early 1950s. Coro was based

on a Leopardi poem which suggests that the living are as fearful to

the dead as the dead are to the living. Petrassi's music often seems

sympathetic to the ghoulish romance of these shadowlands.

The Sixth Concerto's inward communion suggests

a warm nocturne with conversation between the winds and strings. It

is all rather elegant but interspersed with alarms and excursions. Episodes

and mood-switches are part and parcel of this music as is the almost

bel canto tendency to spin long singing lines as in CD2 tr 3

at 11.35. The finale (CD2 tr 4) is bellicose, dysjunct stuff which is

bellowed and rapped out. This eventually collapses into an exhausted

epilogue with only a sporadic shudder and convulsion.

The Seventh Concerto was first aired at the

ISCM Festival in Venice in 1965. This work is out and out avant-garderie

with little to coax the listener's attention and all the usual panoply

of shakes, shrieks, chirps, jabber and grotesquerie - a far cry from

the creativity and rewards of the Fourth and Fifth Concertos. The BBC

Orchestra displays its dedication and malleable virtuosity (as they

also do in No. 8) but although there are some wonderfully imaginative

coups de théâtre this is not a work to encourage

a return visit.

The Chicago Symphony introduced the Eighth Concerto

on 28 September 1972. Impressions: shadowy baritonal celerity from

the strings, chain rattling, eerie catacombs, furies awoken, stabbing

rushes of sound, dissonant carillons. Imperious it may be but it does

not convince in the same way that we are heart-won by the works of the

1940s and 1950s. Is this a case of Petrassi going through the fashionable

academic motions of the early seventies, I wonder?

These recordings were made between 1972 and 1979 and

sound well in their ADD attire.

Zoltán Peskó is the unifying figure in

this historically significant cycle and we should be grateful to him,

to Warner and to Fonit-Cetra for reviving these Italia tapes.

While other ears than mine may discern greater beauties

and rewards I am most confident in recommending to adventurous listeners

the Fourth and Fifth Concertos. The Stravinskian First tickles the ear

but the others are for souls who delight in the ghoul-infested swamps

and mists of the 12-tone school. The Eighth is not a work to which I

want to return.

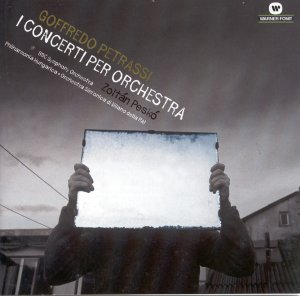

On the cover of the CD a picture of Peskó and

of Petrassi would have been preferable to the chosen stab at symbolism

- a monochrome of a man holding a corroded mirror in front of his face

with the reflected surface towards the watcher but here reflecting only

the sky.

Rob Barnett