The first biography of Sir Malcolm Sargent appeared

in 1968, a year after his death. Written by Charles Reid (whose biography

of Beecham had been published in 1962; one on Barbirolli was to follow

in 1971), it had Sargent’s sanction and in many ways was a fair and

thorough portrayal. Reid had collaborated with his subject who had even

read drafts of several chapters and made suggestions. This partnership

continued up to Sargent’s death, after which, as Reid put it in his

foreword, ‘the members of the Sargent family have not seen fit to continue

Sir Malcolm’s co-operation’. He generously concluded his foreword with

these words:

It had been conveyed to me by an eminent musical

personage, however, that it was feared I might be making too much

of ‘Sir Malcolm’s weaker side’. What this weaker side might be was

not defined. Malcolm Sargent had his limitations. He had his vanities.

He made his mistakes. I trust that these have not been overstated.

What concerns me far more is Malcolm Sargent’s strengths. These I

have stated as eloquently as I could. They were a need of his time.

They are an exemplar for times to come.

Reid’s Malcolm Sargent: a biography (Hamish

Hamilton) went into paperback.

Now, nearly thirty-five years after Sargent’s death,

it is time for a re-assessment, and in writing this new study Richard

Aldous has generally been extremely thorough in his research, so much

so that there are clear differences of fact between the two books. Aldous

even suggests that Reid’s job was to ghost-write Sargent’s autobiography,

whereas Reid made it clear that at Sargent’s suggestion, once he had

agreed to the publisher’s choice of biographer, it was to be a collaboration:

Reid would write the main narrative while Sargent would ‘intercalate

chapters of comment and perhaps additional biographical matter at various

points’. In the summer of 1967 Sargent read 300 pages of Reid’s typescript

‘and confirmed that he would be contributing chapters of his own’. Aldous

writes that on Sargent’s death Reid ‘possessed enough material from

the ghosted memoir to create a fair and well-written contemporary biography’.

He goes on to say that ‘Reid’s book ignited a debate from which the

conductor’s reputation has never recovered’. Those who grew up in the

Sargent era may look on this as a slight exaggeration: the book only

put into print what was already known. Much of the less palatable side

of Sargent’s character was only too familiar.

Aldous, however, has benefited from being allowed

access to much information that Reid was denied, and a series of well-conducted

interviews (including those with Sir Malcolm’s secretary-cum-manager

Sylvia Darley, and his son Peter) has added considerably to the overall

picture of the man. But if Reid’s biography could be said in any way

to have damaged Sargent’s reputation, Aldous’s book is hardly the corrective.

He opens new doors on Sargent’s womanising and his affairs. Of his marriage

Reid told us that he had fallen in love ‘with a slim, elegant girl’

who lived at Beyton, Suffolk who ‘was a keen rider and made many friends

in Melton hunting circle’. Rather more bluntly Aldous tells us that

Sargent’s doctor and regular golfing partner ‘must have been shocked

to discover that Sargent was sleeping with one of his domestic staff

. . a servant girl, just an ordinary maid’. Reid wrote of an idyllic

wedding, ‘of warm sunshine, silver lame and on English lace’ at which

the bride’s uncle officiated. Aldous paints a very different picture:

a shot-gun wedding because Eileen had become pregnant, followed by a

very difficult birth.

But quite the most extraordinary divergence is

Aldous’s belief that single-handed Sargent formed the London Philharmonic

Orchestra. While he refers elsewhere to Thomas Russell’s Philharmonic

Decade (Hutchinson 1944) which covers the formation and early days

of the orchestra, he presents the facts in a very different light from

other commentators. Russell made it quite clear that Sargent became

involved because of the extra work he could bring the orchestra through

his involvement with the Royal Choral Society concerts, the Courtauld-Sargent

Concerts and the Robert Mayer Children’s Concerts. Jerrold Northrop

Moore’s Philharmonic Jubilee 1932-1982 – A Celebration of the London

Philharmonic Orchestra’s Fiftieth Anniversary (Hutchinson 1982)

credits Beecham alone, adding that the above-mentioned organisations

‘brought in Malcolm Sargent as conductor of many concerts’. Robert Elkin

tells a similar story in Royal Philharmonic (Rider and Co. 1946)

while Alan Jefferson, in Sir Thomas Beecham: A Centenary Tribute

(World Records 1979), states that ‘Courtauld and his wife had previously

offered Sargent the task of raising a new orchestra which they would

support, but he declined the opportunity.’ George Roth, cellist in the

new LPO, recorded his memories of the orchestra’s formation in the January

1983 edition of ‘Undertones’, the Newsletter of the RPO Club,

an extract of which was reprinted in The Sir Thomas Beecham Society

Newsletter No 100, April 1983. Nowhere does he mention Sargent;

he makes it quite clear that he and other players were joining Beecham’s

new orchestra. Yet Aldous quite simply asserts that Sargent ‘assembled

106 players’, the new organisation was named the London Philharmonic

Orchestra, and that the first season was divided equally between Sargent

and Beecham, with Sargent ‘deferentially’ taking the title of Auxiliary

Musical Director. He adds that ‘Sargent’s professionalism ensured that

the orchestra was on top form at its public debut’ – yet on 7th

October 1932 it was memorably conducted by Beecham to ecstatic reviews!

He goes on to say that Beecham ‘capitalised on Sargent’s illness in

1933 to assume full control of the London Philharmonic Orchestra’ and

‘in 1935 sacked eight members of the orchestra’. There is no questioning

the fact that Sargent was to some extent involved in the formation

of the London Philharmonic, especially near the end of July and at the

beginning of August 1932 when Beecham was conducting opera in Munich.

But to credit Sargent alone with the formation of the orchestra and

to be able to read (p.217) that in 1962 ‘Sargent had finally made peace

with the orchestra that he founded in 1932’ is little short of ludicrous.

Nevertheless, Aldous has written a very readable

and often entertaining book. It has many strengths and he rightly highlights

what was probably Sargent’s ‘finest hour’ – the war period when he brought

music to a Britain of blitzes and black-outs. But this new biography

shares a weakness with Reid’s study: neither writer seems to be in sympathy

with Sargent’s repertoire, most notably English music. An essential

ingredient is therefore missing: it is as if, to paraphrase a familiar

saying, ‘through and over the whole book another and larger theme "goes"

but is not heard’. Reid admitted that ‘in music there was no great affinity

between Sargent and myself’. Aldous does not show any love or knowledge

of the music which is the backbone to this life, writing, for example,

of Elgar’s The Dream of Gerontius lasting ‘two and a half hours’(p.110).

He is unnecessarily - and unfairly - harsh and dismissive of Boult and

Barbirolli, and even of works, tossing away Holst’s Choral Symphony

as ‘an uninspired work, rarely performed, and disliked by choirs and

orchestras’ (p.222).

Sargent’s repertoire may have been limited, but his

championing of British music really deserves a more thorough examination

than Aldous allows. Elgar remained his chief love, and while he conducted

Gerontius regularly, during those years when Elgar’s reputation

was at its lowest ebb he kept faith with the two oratorios, The Apostles

and The Kingdom, even though they would result in less than half-full

halls. Two performances he gave of The Apostles during the Elgar

centenary won especially high praise from the critics. He championed

both symphonies, particularly the Second (always observing the tenuto

on the trombones during the second of those two dramatic and climactic

breaks in the first movement, two bars after 65), and a memorable performance

of The Music Makers at his 70th birthday concert in

April 1965 preserved in the BBC Sound Archives and once issued on Intaglio

is a fine testimony to his conducting of Elgar.

Neither should one forget his championing of Delius.

It was he, not Beecham, who gave the première of Songs of

Farewell in 1932, a work he committed to disc, and he gave many

performances of A Mass of Life, most notably at the 1966 Proms.

After Charles Groves had revived Delius’s Requiem in Liverpool,

Sargent had planned both to record the work and perform it in London

in a concert that was also to have included the Cello Concerto with

Jacqueline du Pré. (On Sargent’s death, Meredith Davies took

charge of the recording for EMI while du Pré never played the

Delius concerto in public.)

He also championed Walton and invariably brought off

Belshazzar’s Feast splendidly, having premièred at Leeds

in 1931. The flautist Gerald Jackson once wrote of Walton’s conducting

of his own music: ‘I feel that he conducts his own music as well as

anyone else, with the possible exception of Sargent, who of course introduced

and always makes a big thing of Belshazzar's Feast.’) Sargent

oddly spoke of Walton having miscalculated where the chorus is divided

in the final section and had his choirs sing as one. But there were

helpful ‘amendments’. At figure 14, after the a cappella ‘shall

be found no more’ he had the tenors – always the weakest section in

an amateur choir - delete their exposed solo ‘be found’ so that they

could hear the strings and be sure of entering with ‘no more’ in tune.

His last Prom performance of that work was, in the words of The Times

critic, ‘as vivid and thrilling a performance as we have ever heard’.

Even The Daily Telegraph critic wrote that ‘there is no conductor

who understands the complex rhythms and tensions of Belshazzar's

Feast better than Sir Malcolm’. There was unanimous critical praise

too for what turned out to be his last Gerontius at the Proms,

in 1966. (‘Sanctus fortis’ was for Sargent an affirmation of faith:

for those who sang under him his range of facial expressions presented

a more human image of the man than the sleekly tailored person the audience

viewed.)

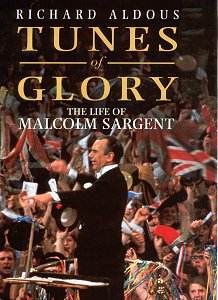

Today, to many people, the mention of the name of Sargent

conjures up a picture of him, carnation button-holed, amidst a sea of

banners and Union Jacks at the Last Night of the Proms, and probably

little else. His appearance at the 1967 Last Night, when he had almost

literally dragged himself from his death-bed, was the final act of either

a great showman or a very courageous man wanting to bid farewell to

his beloved audience. Probably both. The image of Sargent the showman

is what as much as anything has tarnished, if not damned, his reputation.

Reid wrote of some professional quarters nurturing a prejudice against

Sargent: ‘they damned or faintly praised his performances before he

even lifted the stick’. A life-long friend was Sir Thomas Armstrong

who had the highest regard for Sargent the musician. Just before

the end of his life, frail but mentally alert as ever, Sir Thomas shared

his memories in a broadcast interview [August 1994] with Daniel Snowman.

He spoke of Sargent as having ‘the most marvellous talent, and he had

many good generous virtues; he was kind to many people and I loved him

. . . I really loved him’ (a comment that should not be misconstrued).

It is a pity that Sir Thomas was not able to say more and that he was

not alive when Richard Aldous was researching and conducting interviews

for his book. More truths, indeed a separate chapter, about Sargent

the musician are what are needed in any thorough assessment. In Philharmonic

Decade Thomas Russell wrote of Sargent’s association with the LPO:

‘No choice of conductor could have been more happy than that of Dr.

Sargent. With his svelte figure, his incisive manner and his conscious

showmanship, added to the enthusiasm which he so easily displays and

arouses, he made the audience feel at once that they were in for a good

time. . . . His Raymond-Massey features, and his well-known facility

for speaking to a large audience, were further assets.’ But the pianist

Cyril Smith, in his autobiography Duet for Three Hands, revealed

another aspect of the man:

His brain is as immaculate as his appearance; it

seizes upon a point so rapidly that he seems to sense what the pianist

wants of the music even be fore he begins to play it. He takes the

unexpected quite calmly, as he did with me during a particular performance

of the [Rachmaninoff] Paganini Variations. There is one variation

in which the pianist’s hands have to rush up and down the piano independently

of one another, and in which he can easily take the wrong turning.

I did, and still have a horrible memory of watching my hands uncontrollably

playing entirely different sections of the music. For a moment I could

not think how to bring them together into the F major harmony, but

Sargent realised what had happened and rapidly collected the orchestra

to lead me back into the correct passage. He has an incredible speed

of mind and it has always been a great joy, as well as a rare professional

experience, to work with him.

These are points worth bearing in mind when Sargent

is readily dismissed out of hand. While one would not for a moment dispute

many of the criticisms made about him, points that Richard Aldous discusses

very fairly in this new biography, nor indeed would one want to be rash

enough to make too strong claims for him, it would be good for a moment

to set the showman and his button-hole aside and consider music alone.

Many of those of grew up in Sargent’s time may feel he occasionally

deserves a kindlier appreciation than his name is accustomed to receiving.

It would be a pity if this were the last word on the man.

Stephen Lloyd

See also review by Christopher

Fifield