Malipiero’s vast output includes 17 symphonies, 8 string

quartets, a huge amount of orchestral music, many concertos as well

as 35 operas, most of which are still little-known nowadays. Malipiero’s

operas are rarely heard, let alone recorded, though they may be considered

as his most original achievements. His desire to free opera from superficial

verismo led him to make a drastic reassessment of the dramatic

concepts in his own stage works. He thus gave up the principle of narrative

continuity in favour of a free dramatic form which has often been referred

to as "panel structure". His first significant stage work

is the triptych L’Orfeide (first performed in 1925) of

which the central panel is the epoch-making Sette Canzoni

of 1918. (The other panels are La Morte delle Maschere

and Orfeo.) The basic idea of unconnected or unrelated

episodes which forms the very core of Sette Canzoni is

carried forward into other stage works such as Torneo Notturno

of 1929.

Several operas were composed during the fascist period:

La Favola del Figlio Cambiato (1932/3), Giulio Cesare

(1934/5) after Shakespeare and Malipiero’s only "traditional"

opera (and also the only one having an overtly political meaning), La

Vita è Sogno (1940/1) and I Capricci di Callot

(1942). It seems that Malipiero’s attitude during the fascist period

in Italy was rather ambiguous, as was the younger Petrassi’s. (Malipiero’s

and Petrassi’s attitude changed radically when the German troops settled

in Italy.) With the possible exception of Giulio Cesare,

the other operas of that period tended to avoid any direct allusions

to the political or social realities of the time. By reviving the use

of the masks of the Commedia dell’Arte, as in the prologue of

I Capricci di Callot, the composer conjures up an unreal,

artificial world with very little direct concern for, and much oblique

reference to, reality. (Masks often feature in Malipiero’s work, e.g.

La Morte delle Maschere or the piano suite Maschere

che pasano of 1918.) In I Capricci di Callot,

"the grotesque, the bizarre and the disturbing prevail" (Andreas

Meyer). Indeed the libretto by the composer may contain allusions that

were quite obvious for Malipiero’s contemporaries, much less so for

present-day listeners, though they may not be that relevant to our appreciation

of the work as music.

I Capricci di Callot, subtitled Commedia

en tre atti e prologo, is based on E.T.A. Hoffmann’s tale Prinzessin

Brambilla modelled on Callot’s etchings Balli di Sfessania

featuring grotesque figures of the Commedia dell’Arte. (Walter

Braunfels’ comic opera of the same title was premièred in Stuttgart

in 1909 and prompted Busoni to compose his own Brautwahl

based on another tale by Hoffmann.) Malipiero however admitted that

he considerably departed from Hoffmann’s capriccio while devising his

own libretto.

I Capricci is a typical Malipiero opera

in that its structure considerably differs from any traditional scheme.

It opens with a seven-minute long orchestral Introduzione followed

by a ten-minute long Prologo in the form of a pantomime in which

many characters of the Commedia dell’Arte are featured and which

does not seem to have any relevance to the rest of the play. It may

simply mean that the actual play is but a dream. The plot, if such there

really is, is fairly simple in outline though it includes a good deal

of ambiguities and avatars. Giacinta, a poor seamstress, dreams that

she is a princess whereas her lover Giglio, a mediocre actor, dreams

that he is the Prince (i.e. the part he always wanted to play but never

did). Both are caught up by their dreams and carried away from reality.

Giglio, as the Prince, must free the Princess. Giacinta, dismayed that

he might love another girl, leaves him. Act 2 opens with another long

orchestral introduction depicting the carnival taking place in the city.

Everyone wears a mask: Giacinta as the Princess, the Charlatan (in reality

he is the Prince), the Doctor (i.e. the old Beatrice). Beatrice tells

Giglio that Giacinta is in jail because of him, while the Charlatan

appeases him by showing him Giacinta at a window of the palace. Giglio

hurries to her but is stopped by the Poet who wants to read his last

drama especially written for him. Giglio falls asleep and the enraged

Poet summons the people to beat Giglio who is taken into the palace.

Act 3 is in two scenes separated by a long orchestral interlude Danza

funebre in morte di una bambola (a funeral march for whom? For what?

We are not really told). In the first scene, an old man reads the story

of Princess Militis (who is she really?) whereas Giglio slowly wakes

up, catches a glimpse of Giacinta who disappears again. After the interlude,

back in the dressmaker’s basement. Giacinta is still looking for the

Prince. Giglio reproaches her for her doubts about his faithfulness.

They are at long last reconciled and get married. The Poet and the Charlatan

reappear followed by Callot’s masks, and all join in a final ensemble

:

"Everyone has believed in the truth which this

story relates with borrowed words".

Malipiero has been blamed for writing a comedy completely

at odds with the realities of war in much the same way as Poulenc when

he composed his burlesque opera Les Mamelles de Tirésias

in 1944. But it is fairly evident that Malipiero’s masks were a way

to hint at the situation in Italy without running the risk of some official

reaction on the regime’s part. But, after all, the most important thing,

by which any opera succeeds or fails, is the music. That of I

Capricci di Callot is simply superb and shows Malipiero at his

best and at his most richly melodic. The score abounds with beautiful

arias (each main character has his/her moment of glory) and ensembles,

whereas the orchestra – a major protagonist, always present but never

drowning the voices – literally shines throughout. Malipiero’s lyricism

expresses itself generously, often in quite simple but telling terms

without ever falling into the trap of sentimentality. The whole score

of the opera is a real miracle.

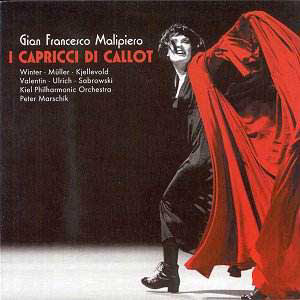

I must confess that all the singers here are completely

unknown to me, but I have been – and still am – quite impressed by their

achievement. Martina Winter as Giacinta and Gro Bente Kjellevold as

the Old Beatrice steal the show, but each of the soloists is excellent

and the Kiel Philharmonic Orchestra in great form support them with

obvious enjoyment and prove themselves a very fine body of players.

Peter Marschik conducts a vital, committed reading of a score he obviously

loves. This is a live recording but you would never guess it given the

quality of the audience’s silence and the absence of any distracting

stage noises. A magnificent piece, excellent performance, very fine

recorded sound and outstanding production with generous and most informative

notes by Andreas Meyer and Tilman Schlömp.

At the start of the enthusiastic applause greeting

this performance, someone is heard shouting Bellissimo!. There

is really nothing to add to this. Warmly recommended. The finest operatic

recording I have recently heard.

Hubert Culot

![]() See

what else is on offer

See

what else is on offer