The recording companies use all sorts of means by which

to recycle old performances from their vaults, the most common being

to invent a series such as, "great conductors/artists of the past",

"great historical recordings", and so on. It is easy to be

cynical about this and some of the stuff that is wheeled out in these

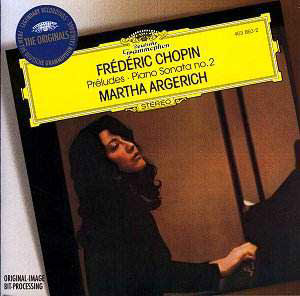

circumstances can be questionable. Here we have a disc in Deutsche Grammophon’s

"Legendary Recordings" series but I cannot imagine that anyone

would quibble at the application of the term "legendary" in

this case.

DG have put on the one disc two complete, major Chopin

works. This is apt because Martha Argerich never got near to recording

the complete Chopin oeuvre: for example, there is no set of the

Mazurkas available to posterity.

In this complete version of the Preludes, recorded

twenty seven years ago, the tigress of the keyboard laid down one of

her finest Chopin performances.

Chopin conceived the preludes as a set (although they

are often played as stand-alones) and handled correctly they cumulatively

become a powerful single musical experience. All twenty-four keys are

used, each major key prelude being followed by its relative minor. The

composer cycles through them starting in C major and ends with the final

pair in the closely related keys of F major followed by its relative

(D minor). The most remote keys are reached in the middle and, generally,

these preludes tend to be more complex, reinforcing a feeling of moving

into remote territory before returning home. It is a principle inherent

in sonata form.

I apologise if this is a bit technical for some, but

it helps to show the overall design, an aspect of the music that not

all pianists, including some great ones, seem to take into account.

A feature of the work is the contrast between preludes – an elegiac

number may be sandwiched between displays of virtuosity con fuoco,

and therein lurks a potential enemy of a grand design approach.

The group of nos. 16, 17 and 18 is a case in point. Pianists who are

seduced into overdoing the display side of 16 and 18 are in danger of

unbalancing the work.

Argerich delivers no 16 in inimitable tigress fashion

with frightening panache and virtuosity, repeating the performance for

no. 18. That makes them fabulous on their own, but it is the sort of

thing that can militate against the overall flow of things. What is

the fate, for example, of the lyrical no. 16, mercilessly squashed between

this heavyweight display? Well, Argerich strengthens the lyricism with

a kind of masculinity (if I may use the term) that somehow enables it

to take the strain. By this and other means she achieves what ought

to be the impossible, a satisfying whole whilst not keeping on the lid

when a head of steam is building.

She does several things which, in passing, caused my

eyebrows to raise. For example, the restraint of no. 4 in E minor is

over disturbed by a climax, the strength of which is surely not inherent

in the piece. The Raindrop Prelude (no.15), with its repeated

A flat throughout I have always considered gains power from an incessant,

steady approach but this is not Argerich’s way. These are, admittedly,

personal quibbles that are overridden by the overarching consistency

of approach that is inimitably Argerich. Some may wish the lyrical preludes

were more sweetly lyrical and the contemplative ones more deeply contemplative,

but the overall impact is such that for many this is the finest Chopin

prelude set ever recorded. One would expect tough competition from the

likes of Pollini and Kissin. Both, like Argerich, can make hair-raising

pianism sound easy, but Pollini sometimes gives an impression of being

emotionally switched off whilst Kissin charges thoughtlessly at the

music with a freneticism that cannot allow for the kind of cumulative

impact achieved by Argerich.

Some of the music in the preludes sounds like a trial

run for the Second Sonata, for example the trio of nos. 16, 17

and 18 mentioned above. The Finale, in its shortness,

could easily serve as a prelude. Argerich’s rendering of it, an impossibly

smooth sounding combination of speed and virtuosity with restrained

dynamic, I find unrivalled. In the Funeral March third movement

she is, predictably, less successful. Hers is not a deep contemplation

on the mysteries of death. Nevertheless, like the Preludes, the

whole work has an overall power that is uniquely Argerich.

A great Chopin disc.

John Leeman

![]() See

what else is on offer

See

what else is on offer