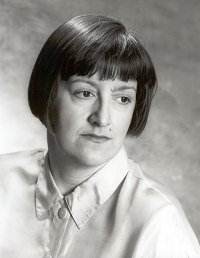

Judith Bingham. A Fiftieth Birthday interview with

Christopher Thomas.

Judith Bingham is that seemingly rare thing in contemporary music. A

composer whose music has the ability to connect and communicate with

its audience on an immediate and direct level. One needs to look no

further than her 1997 Piano Trio "Chapmanís Pool" for

evidence. In an age where second performances are often more crucial

to composers than the first there can be few recent works to have received

over eighty performances in four years, a feat to make many composers

(and publishers!) green with envy.

The secret of this success can be seen on several levels.

A glance through Binghamís catalogue reveals a considerable struggle

to find any piece that does not have a strongly visual or literary theme

behind its title, giving the listener an immediate window to access

the unique world of each work. The stimuli can be wide ranging, from

Errol Flynn to ancient Egypt yet there are certain recurring subjects

that continue to provide inspiration, amongst them a fascination for

alpine and winter scenery, the sea, mythology and the writing of Shelley.

This is not to say that her work is not without itís darker side. Bingham

is not afraid to unsettle her listener where appropriate, with a good

number of pieces exhibiting what the composer describes in her own words

as a "painful kind of beauty". The music itself, whilst often

chromatic with a strictly controlled use of dissonance where it serves

the music, does so within a framework that always exhibits structural

unity through a strong sense of melodic, harmonic and often rhythmic

direction. A clue to Binghamís practicality as a composer lies in her

background as a professional singer, having spent around twelve years

as a member of the BBC Singers. It is no surprise therefore that choral

music forms a central thread through her entire output, singing having

been a part of her life from very early on.

"Singing was always there. My father was musical

although my upbringing was in a very ordinary lower middle class family,

father was a tax inspector and my mother was an auxiliary nurse. My

father played the piano and did a certain amount of amateur playing

and I was one of these kids that crawled up on the piano but there was

always music around. I grew up on the big symphonic repertoire that

my father liked, standard stuff, Beethoven, Brahms, Schubert and I had

all the records that every child still has, Carnival of the Animals,

Sorcerers Apprentice and the like".

Composition started relatively early although like

many composers memories of the initial attempts are hazy.

"I can remember playing a piece that I had written

to my father when I was about eight although I think I was writing before

that but I never wrote anything down. It was all very secretive though

and nobody really gave me any encouragement or help".

By her mid-teens singing was becoming a major part

of her life and joining the Sheffield Philharmonic Chorus brought an

opportunity to experience music making on a new level.

"My claim to fame was taking part in Barbirolliís

last Messiah but there were concerts with the Hallé and all sorts of

people came in like Barenboim and Antal Dorati. I also started to take

an interest in the theatre but there was never any question that music

would be my vocation. By this time I was writing quite big pieces, but

very much on my own, nobody was taking any interest. I thought of myself

as a bit freaky because I did not even know there were women composers.

I had no real role models although I adored Berlioz. There was little

contemporary music but when I came up to London and went to the academy

I remember Maxwell Davies and the Fires of London and that was very

influential".

Amongst her colleagues at the academy were such luminaries

as Felicity Lott, Graham Johnson and Simon Rattle, yet the path was

not always easy with little encouragement from her parents and teachers

who felt that she should be concentrating her studies on the oboe, "which

I played at school and hated". Having works looked at by others

for the first time proved difficult.

"At first it was pretty disastrous, I was very

difficult to deal with and would not accept criticism at all. I had

Malcolm Macdonald at first, Eric Fenby for a while and then I went to

Alan Bush for about a year and eventually John Hall. Nobody seemed to

get the measure of me but I thought I was Berlioz. I had absolutely

no practicality or idea as to how I was going to achieve what I wanted,

I just knew I was going to do it. When I left I still thought of myself

as this romantic Berlioz figure but I was lucky to be getting commissions

right from the start although I was only charging about twenty pounds.

I remember one person paying me in cash from his wallet! Many of the

people I knew well at college became successful very quickly including

Graham Johnson who formed the Songmakerís Almanac and I wrote four pieces

specifically for them, including Playing with Words, Cocaine Lil

and A Little Act upon the Blood".

It was during the year after leaving college, that

a friend suggested sending a score to the BBC New Music Panel. This

proved to be a fateful suggestion for it brought the young composer

into contact with Hans Keller, who was to become not only the first

but also the most lasting influence on Bingham to this day.

"I sent him a pile of scores and he wrote me this

wonderful letter that I took complete umbrage at, saying that I had

the same problem as Beethoven, too many ideas and that I needed to be

more disciplined. I wrote back to him and so started our correspondence

until one day I said if you are so clever why donít you give me lessons

to which he replied alright but you wonít like it. We used to meet in

the old BBC club in Langham House and he would chain smoke and drink

vodka whilst really looking at my scores in detail. I was so innocent

that it never occurred to me that this famous teacher would usually

charge a lot of money for lessons and he never mentioned it. I saw him

for two or three years and he was wonderful, a real father figure to

me. When we stopped seeing each other he wrote me a long letter saying

that I was the only pupil he had never charged for lessons. I was just

so naïve, but he got me some commissions including one for Peter

Pears, which was wonderful. I just wish he were still alive, as I never

had the opportunity to thank him. Unlike the teachers at the Academy

he would never say you canít do that. Instead he would ask what I thought

of a piece and act as an analyst. I had this thing about spontaneity

and not revising pieces and I always remember him asking me what made

me think the spontaneous idea was the first one. I just couldnít see

what he was driving at. It was years later before I understood that

Beethoven filled notebooks before he came up with his spontaneous idea

for the opening of his fifth symphony".

The commissions continued to come in and a steady flow

of mainly chamber pieces were produced in response, one notable success

being the BBC Young Composer of the Year award in 1977 for the harpsichord

piece, A Fourth Universe, together with a work for harpsichord and soprano,

The Divine Image. "I remember singing in the concert, I still have

a tape of it in fact". In spite of these early successes it was

not all plain sailing.

"There was a time in my late twenties where I

kind of lost hope for a while, my music had sunk into this turgid, awful

rut and I just lost interest. I suppose what brought it all about was

my opera about the life of Errol Flynn, which with the libretto and

the music took two years to write. I spent a long time trying to put

it on myself but the whole thing was disastrous and I ended up shelving

it. It threw me into a very depressed state for two or three years but

then a series of things happened. I met my future husband, joined the

BBC Singers which gave me a salary, and I also had some therapy, which

helped a lot. I was a lot more emotionally stable and got myself over

the kind of writers block that I had, so things just took off again".

The work that was to prove crucial in this reversal

was Binghamís first orchestral score, Chartres, inspired by the

overwhelming impact of a visit to the great cathedral. In some ways

it was a long time in coming, written without the aid of a commission

and occupying over a year in its creation.

"Itís the only big piece that was not written

to commission. A huge work, thirty five minutes and of course although

everyone said it was very interesting no one wanted to do it. I finished

the score in 1987 but it was 1993 before the BBC Philharmonic took a

flyer at it. By that time, as with Flynn, I had given up on it. It was

Jane Glover who asked me if I had any chamber orchestra pieces suitable

for the London Mozart Players, to which I replied no but I have got

an orchestral piece! It was a huge turning point in my career. There

was a big reaction to it and virtually the first week it was performed

I got four other big commissions including another orchestral piece

for the BBC. It was wonderful".

The years since 1993 have seen a succession of major

works, both orchestral and chamber, although there are still the ever-present

choral pieces. Many of these works seem to be written with astonishing

speed, indeed there are few contemporary composers as prolific with

ten works written in 2001 alone (the composer modestly points out that

some of these works are relatively short!). The success of Chartres

opened the gates to some prestigious commissions including Beyond

Redemption, the work commissioned by the BBC in the wake of the

first performance of Chartres, The Temple at Karnak for

the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra which has since been toured extensively

including a performance at the Vienna Musikverein and Otherworld,

a large scale cantata for the Three Choirs Festival. There are also

a good number of earlier works that have been "discovered"

and taken up by artists some years after their composition.

"It was quite a breakthrough when Mark Bebbington

did my piano piece Chopin. It was years since I had heard it

and although he was enthusing about it I was really quite sceptical.

Yet it went down really well and two other pianists immediately played

it straight away. Even with early works there is virtually nothing that

I have withdrawn or revised. If you write a crap piece history will

judge it and it will just disappear so I have tended to just let things

stand".

Brass bands have also been a source of inspiration,

perhaps not surprisingly for a Yorkshire-born composer, with a succession

of substantial works for the medium throughout the 1990s.

"I was approached by Bram Gay of Novelloís to

write a band piece in the late 1980s and came up with a piece called

Brazil. I thought it was pretty lousy and unusually for me, withdrew

it. I had made all the classic mistakes, it was bottom heavy and I just

didnít rate it but I immediately received two commissions on the back

of it and wrote Four Minute Mile for Leyland Daf Band and The

Stars above, the Earth below, for The Royal Northern College of

Music Band. After that I thought thatís it, I am not doing anymore brass

band music but immediately got the commission for Prague in 1995

and in spite of vowing once again that I was finished with bands wrote

These are our Footsteps in 2000. The thing is itís such hard

work producing them but when you hear the way the bands play it is just

so exciting".

So what does the future hold? There are no shortage

of works waiting for suitable commissions and one major ongoing project

that is going to occupy much of the next year or so.

"Iím keen to do a string quartet and having done

a Piano Trio and String Trio would like to do all the standard chamber

forms, piano quartet, piano quintet etc. At the moment Iím writing a

piece for the cathedral at Bury St. Edmonds which is going to be a huge

sacred music drama, a kind of church opera for performance in 2004 which

is to celebrate all of the new building work which has been done there.

It will involve all kinds of dance elements, the cathedral choir and

solo singers and is based around a twelfth century ivory cross which

was allegedly carved for the cathedral and depicts scenes from the gospels,

with a strong element to do with tolerance as there was a lot of anti-Semitic

feeling in Bury St. Edmunds at the time. Itís really exciting and right

up my street".

In the year that Judith Bingham celebrates her fiftieth

birthday there seems to be no halting the flow of music or inspiration.

One cannot help but feel that with the major successes of the last decade

behind her, the new millennium is likely to bring yet greater anticipation

from her expectant audiences.

© Christopher Thomas 2002

Prologue Chartres

Shelley Dreams

used for the Young Musician of the year 2000

Photo credit © Gerald Place