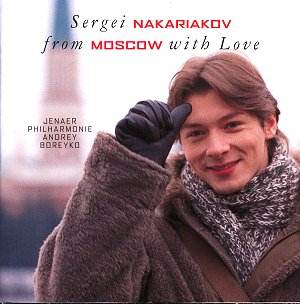

It is inevitable, if somewhat unfair, that Sergei Nakariakov

is likely to be judged by comparison with that other great modern virtuoso

of the trumpet, Håkan Hardenberger. I say unfair because in reality

their careers have taken them in very different directions. Whilst Hardenberger

has built a whole new contemporary repertoire for the instrument Nakariakov

has, by and large, become more synonymous with the lighter and romantic

side of the instrument. One of his other recent releases on Teldec,

"No Limits", features transcriptions of works by Saint-Saëns,

Tchaikovsky, Bruch and Massenet. He makes considerable use of the flügel

horn as well as the trumpet.

Where Nakariakov really is unique is in his extraordinary

rise to fame following his "discovery" at the tender age of

twelve. Brass players are generally quite late to mature, yet Nakariakov

had a recording contract with Teldec at fifteen and is still only twenty

three.

This latest disc couples two original works for the

instrument with a transcription for flügel horn (by the soloistís

father) of Glièreís 1950 Horn Concerto that some may have

heard Nakariakov play at the 2001 Proms. It is the works by Arutiunian

and Vainberg that hold the greatest interest however, also drawing the

finest playing from the soloist.

Born in Yerevan, Armenia, Alexander Arutiunian

combined a career in conducting with composition, being principal conductor

of the Armenian Philharmonic Orchestra for thirty six years until his

retirement in 1990. His Trumpet Concerto is a relatively early

work, written after a two year period of study in Moscow, and plays

continuously whilst falling into three clearly defined sections. Not

surprisingly the influence of Shostakovich is evident very early in

the work (the orchestral introduction to the first principal trumpet

theme at around 1:23 speaks for itself) although the most lasting influence

is perhaps that of fellow Armenian Khachaturian. One senses that native

folk music is never far away and Arutiunian also favours a relaxed,

almost bluesy brand of melody reminiscent of a Shostakovich jazz suite

or film score. For all its influences however this is an attractive

and highly enjoyable work of infectious spirit. Nakariakov is more than

equal to the demands of the work although it is his legato playing in

the slower passages that really shines through.

If the Arutiunian brings out the best in Nakariakovís

lyrical playing it is the Vainberg that succeeds in exploiting

his technical facility to maximum effect. Subtitled Etudes, Episodes

and Fanfares respectively, each of the three movements explores

a contrasting aspect of the instrument and although the dominant force

is Shostakovich, Vainberg consciously weaves a multitude of quotes into

the work. This is notably the case in the final movement which is composed

entirely of cadenza-like references to famous trumpet solos from Mendelssohnís

Wedding March, Bizetís Carmen, Rimsky-Korsakovís The

Golden Cockerel and, although the booklet note does not mention

it, Stravinskyís Petrouchka. I am sure it is no coincidence that

the middle movement is also built on a triplet figure that immediately

calls to mind the opening of Mahlerís Fifth Symphony. Once again here

it is the lyrical element of the soloistís playing that holds the attention.

The opening movement is light-hearted in tone although there is nothing

light-hearted about the technical demands on the soloist, Nakariakov

overcoming them with deceptive, at times astonishing, ease.

As I previously hinted, the weak link here is the Glière.

It is no surprise that for a work composed in 1950 it is astonishingly

backward looking. It does not help however that there is little to distinguish

it melodically although Nakariakovís performance does succeed in warming

the heart somewhat. His mellifluous sound on the flügel horn is

delightful but for all of that I have to say that I would rather hear

it played on the instrument for which it was intended.

The Jenaer Philharmonie may be an unfamiliar name but

they give good support under Andrey Boreyko. With nicely balanced natural

sound to round things off this is a fine release which should give much

pleasure, extending beyond the realms of those with simply an interest

in the instrument itself.

Christopher Thomas