This coupling may at first sight seem unusual, but

there are strong links between Herbert and Dvorák since both

were trained in the German tradition. Before Dvorák moved to

New York, where they met, Herbert had been exposed to Dvorák's

works during his musical training. The two cello works on this disc

were composed in New York within a year of each other, at a time when

both musicians were in close contact and so cross-fertilisation took

place.

Antonín Dvorák went to America

towards the end of the 19th Century (1892) to serve as director

of their National Conservatory of Music of America. Although initially

reluctant to take the post he found the experience of living there a

happy one under charitable support of a Mrs Thurber in New York. The

city so inspired him that he wrote his New World Symphony during

this chapter of his career.

Before the New World's première, Dvorák

had completed the scoring of Klid. In it, a soft and tender

haunting melody from the cello develops with delicate fragments of counter-melody

from the orchestra coupled with elegant flute phrases.

Dvorák had long rejected the cello as a solo

instrument for any of his compositions but after hearing the Herbert

Concerto he started work on such a concerto himself. By this time, however,

American life had lost much of the initial glitter that Dvorák

felt when he first arrived in New York. Also, he was homesick, resenting

the separation from his family back in Europe. Coupled with these sombre

emotions his sister-in-law fell seriously ill during the period of composition.

All this is reflected in the dark 'personality' of this work. The

Cello Concerto opens with an Adagio and a familiar brooding

theme (with an echo of the New World perhaps), which grows into

a powerful passage of rage. This subsides into a peaceful scene where

a lovely horn passage introduces the second subject. A sorrowful cello

and lamenting woodwind transform the main theme into a new melody. The

Adagio ma non troppo gives a spell of idyllic calm that ends

with a peaceful coda. The New World can be heard again (tk.3,

3'36" in); did he expose the New World on purpose? The Allegro

opens in marching rhythm, revisits earlier elements and rounds off with

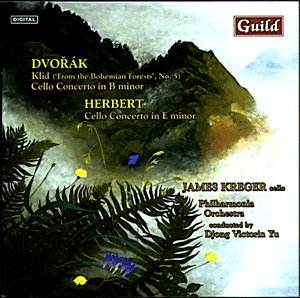

a majestic conclusion. Here, Kreger is agile and good. Eventually the

movement drifts into oblivion.

We can find many recordings of this work in the catalogue

of which the 1968 Rostropovich version under Karajan with the Berlin

Philharmonic [DG 413 819-2] (coupled with Tchaikovsky's Rococo Variations)

is best known and continues to sell well with its sumptuous performance.

Of the versions available this one should not be confused with others,

for Rostropovich recorded the work three times under different  orchestras

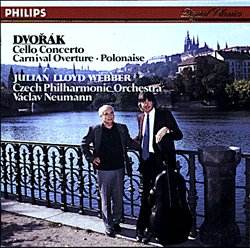

and conductors. Of the recordings without Rostropovich the Neumann version

with Julian Lloyd Webber is a more modern one with which to make a comparison.

Comparing the two we find that Kreger is not as secure as Lloyd Webber

with his late first movement entry and he seems uneasy with the first

bars that follow. However, his romantic passages are full of emotional

nuances and in places are better than those of Lloyd Webber. Both performances

are good and have their respective merits. The Kreger version is a somewhat

slower in the first movement yet faster in the second and third.

orchestras

and conductors. Of the recordings without Rostropovich the Neumann version

with Julian Lloyd Webber is a more modern one with which to make a comparison.

Comparing the two we find that Kreger is not as secure as Lloyd Webber

with his late first movement entry and he seems uneasy with the first

bars that follow. However, his romantic passages are full of emotional

nuances and in places are better than those of Lloyd Webber. Both performances

are good and have their respective merits. The Kreger version is a somewhat

slower in the first movement yet faster in the second and third.

Victor Herbert was born in Dublin, the son of

an Irish painter who died when Victor was quite young. His mother remarried

a wealthy German and the family moved to Stuttgart where the young Dvorák

grew up. It was in Stuttgart that he received his musical education,

firmly that of the German School. Herbert then embarked on a career

as a cellist and composer and joined New York's Metropolitan Opera as

principal cellist with his wife contracted as a solo singer there.

The success of the New World Symphony première

by the New York Philharmonic (in which Herbert played) impressed him

and may have accelerated his thoughts of writing an orchestral piece

in which his cello would feature. Thus this Herbert Concerto came into

being.

Herbert's Second Cello Concerto, again written

in a minor key is also somewhat dark. (It's interesting to note that

Herbert set his concerto in the same key as Dvorák's New World.)

We find that Herbert lacks those masterful skills possessed by Dvorák,

but nevertheless the work is gracefully written and needs a few hearings

to fully appreciate its construction. It follows the three movement

layout favoured by many Romantic composers and is clearly a vehicle

for displaying the sonorous qualities of the cello. The dark and threatening

opening, Allegro impetuoso soon subsides and we embrace more

urgent and impatient themes that echo the opening statement. Herbert

is skilful in his development of the opening cello motif with imitations

from the orchestra, one just wishes that he had chosen another motif!

(We are told, in Benjamin Folkman's notes, that we open with a question

to which the orchestra provides an answer.) The Lento takes us

to pastures new with its tender theme lovingly played. The Finale,

Allegro moderato returns to the impatient mood of the opening with

(this time) cheery transformations of the opening motif.

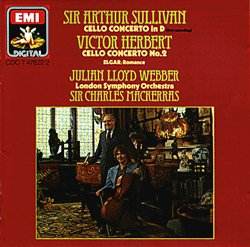

This work is not frequently recorded but one memorable recording is

that by Julian Lloyd Webber on the EMI disc, coupled with the première

recording of Sullivan's Cello Concerto, with the London Symphony Orchestra

under Mackerras. Mackerras is leisurely with his readings of the first

and second movements, particularly the second, which is over half a

minute longer. In the third, Lloyd Webber is lighter and more vivacious

than Kreger. Here the pace is reversed and Yu is the more leisurely

by over a quarter of a minute.

Cellos vary in tone and can influence one's feeling

towards a player's style, particularly in the lower registers: however,

it is often a matter of listeners' tastes. Both Kreger and Lloyd Webber

possess excellent instruments yet I personally favour the warmer tone

of Kreger's. They are both excellent musicians and there is much to

stimulate the listener with either of the recordings. In the Guild recording

the orchestra is rich in texture and Yu's delivery is strong, with the

soloist well supported as with Neumann and Mackerras. The placing of

the cello is spot-on and although the acoustical balance is good some

orchestral sections are at times unnecessarily recessed. The first violins

could have done with being brought forward to ensure the cello does

not mask their charming counter melodies. In contrast, some of the pizzicato

passages are very forwardly focused.

The notes in English, German and French are detailed

and give a good background to the writing of the pieces.

Raymond J Walker