Besides a considerable amount of organ and choral music,

Langlais composed three organ concertos (1949, 1961 and 1970/1 respectively)

which have never been recorded so far. His Réaction – Organ

Concerto No.3 was completed in 1971 and first performed in 1976

in Pittsburgh. The subtitle is rather puzzling or misleading, for there

is nothing reactionary in this substantial work cast in a clear 20th

Century idiom, even though Langlais’s organ writing may be somewhat

less adventurous than Messiaen’s. The opening drum-roll followed by

a nervous gesture in the strings sets the scene: this will be a serious

often dark-hued, intense piece of music with very little relief, if

indeed any at all. The structure, in five interlinked sections, is unusual:

a long weighty introduction stating the concerto’s basic thematic material

leads into a short, nervous Scherzo fading into the real core of the

entire work: a powerful fugue sometimes recalling Honegger’s muscular

and virile writing. This is followed by a cadenza leading into the final

short coda. Neither reactionary nor revolutionary, Langlais’s Third

Organ Concerto is an intensely serious and powerful work of substance.

Helmschrott too has composed (and, presumably, still

does so) a huge amount of organ music, in which his large-scale cycle

of twelve Church Sonatas (the First Sonata for trombone and organ was

written in 1984 as a commission by the Department of Culture of Ingolstadt)

has the lion’s share. Some of his orchestral and vocal music is also

available on Vienna Modern Masters (Entelechiae for soprano

and orchestra of 1977 on VMM 3035 and his oratorio Kreuz und Freiheit

on VMM 3027). His Lamento – Concerto for Organ, Strings and Percussion,

another Ingolstadt commission, was completed in 1993 when the composer

was artist-in-residence at the McDowell Colony. It is laid-out in two

weighty movements of broadly equal length framing a short Interludium.

All the main material is based on an eight-tone row stated at the outset

of the work. The first movement is mostly dramatic and declamatory in

mood. It generates considerable tension, briefly dispelled in the peacefully

musing Interludium. The second movement displays some forceful

energetic writing. A slower middle section eases the nervous tension

before the powerful reprise rushing the concerto to its emphatic conclusion.

A substantial work and a most welcome novelty whose deeply felt and

intense earnestness of purpose sometimes recalls Frank Martin in its

freely atonal but highly communicative idiom.

By comparison, Poulenc’s better-known Organ Concerto

in G minor (one of his supreme and most perfect masterpieces,

by the way) might seem lightweight, which it is not. Quite the contrary;

it is one of his most serious and most personal statements. It is miles

away from his customary, easy-going and light-hearted playfulness, that

nevertheless often conceals some deeply rooted sadness. However l’ironie

est la politesse du désespoir, a saying that often applies

to Poulenc’s bitter-sweet music. Poulenc, however, was also a deeply

religious man who expressed his faith in short choral works as well

as in his large-scale trilogy of choral-orchestral works culminating

in his last masterpiece Sept Répons des Ténèbres.

Though not overtly religious, the Organ Concerto belongs to his most

personal music making, even if it has that playful sixth section inspired

by the sight of serious monks playing football! Poulenc, who was not

trained as an organist, admitted that his model was Buxtehude, though

the final product is pure Poulenc. Maurice Duruflé, who gave

the first performances of the Organ Concerto, also acted as technical

adviser during the composition of the piece.

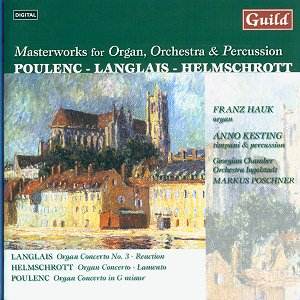

Guild’s hopefully ongoing series is going from strength

to strength, thanks to Franz Hauk’s dedicated advocacy and persuasion.

Of Guild’s enthusiastic support. I now hope that forthcoming releases

in this series will include any (or all!) of the following: Rainer Kunad’s

Organ Concerto (with double string orchestra and timpani) as well as

those of Hamilton, Hoddinott and Mathias, and – why not? – Langlais’s

First and Second Organ Concertos.

Production is excellent and up to Guild’s best standards.

The recording team again cope quite successfully with Ingolstadt Liebfrauenmünster’s

reverberant acoustics. Another warm recommendation.

Hubert Culot